Lo Kwa Mei-en’s inaugural poetry collection Yearling asks no easy questions and provides no single answer—rather, it gives us duality warped over and over. She moves effortlessly between the violently sexual and sexually violent, the poems overlapping one another, not unlike an embroidered backstitch. Images and language are reused and re-imagined; we never read them the same way twice. The sea is dark and ruthless in one moment and the tides are agents of change, “made in the image of a shut door,” in the next. Embedded in this interweaving is the glimpse of a family narrative, of migration, and of the cyclical nature of a woman’s place in that journey. The speaker never shies away from self-damnation (“I am half-spent and hell-bright as / the bad ones are, mother, a flicker deeper than the sea”) and we feel the crushing weight of feminine expectation in “Rara Avis Decoy”: “My name is I know not what I am / as a country of mothers and fathers comes down.” Mei-en gives us a grim and foreboding portrait of the future in “The Extinction Diaries: Psalm” when “the white coin of vertebrae // in a bowl of hips tells the future. May the meek inherit / something dangerous. May I.”

The book’s three sections are rife with animal imagery and allusions, and the through line of a vulnerable yet ferocious speaker never fails to give the poems corporeality. “You don’t get / to know my real name, what to say and louder yet when // on top of me, making me shake like a head,” she says in “Pinnochia from Pleasure Island.” The undoubtedly female speaker deals out commands to a presumptive lover with no hesitation: “Go to all fours and run, don’t walk. […] In the reddest room, someone else can be your / Christ for once,” from “Tales of Burning Love.” The speaker’s objects of desire vary wildly—they may take the shape of water or the body of a canine—yet we are always startlingly reminded of the beauty in sexual carnage. She is insatiable in her search for what renders the body both violated and pleasured, both human and animal. From “Canis lupus familiar song of songs”:

When I’m got, when she’s good, the omega

bitch rises up like a gorgeous, violet weed. She runs high like

an arrow unleashed. She takes her tail in her mouth. Accomplice

stars gnaw on the dark. This is how we want to make love out

at the fence—in fat grass, a hound at our back, knees rocked

& boxing a dent under a belled, red alarm of alien honeysuckle,

bodies folding out until huge fogs & landscapes that spell I, I,

I was prepared to die.

This first poem of the final section marries a dismal civilized life with the instinctual roving of beasts. It is a rounding-out of the dystopia at the edges of earlier poems. The language accelerates and culminates in an explosion of something like an urban landscape. “So female weeds upset the asphalt like a broken wine, & wild / dogs butchered my heart and fled before it blew […] A red illumination to light the animal amen.” We often land on this hued image, not rose-colored but blood-soaked; an homage to birth and death.

We who dream the freak

currants of November, dream the high tides,

the final map of a body lost at last, touch them and go

blind as the chain link eyes of the fence. The hand

I adore wades through the red, raptured currants.

I dream I will never shut my eyes again, and this time

I can see it. I heard a bell through blood.

This excerpt from “The Currant” shows its obsession with empty places and partitions, inevitably calling to mind the boundless swaying of the seas and of the body. This pairing recurs—the speaker of many of these poems seems obsessed with imbibing from a “well with a false bottom, / no pit, I drink from you” and the largeness of “what beasts below a wave bigger than us at all.” Water in these poems is overwhelming yet necessary, and the most feminine element.

Preoccupied by the female form and function, Mei-en gives us more than one allusion to damned women of mythology. Eve, most often. Ophelia. Even the speaker herself becomes her own mythology. From “Rough Husbandry”:

After you, I begin at the Natal plum:

a babe with one hand

stuck in the terracotta O of my first jaw.

When I bite back, the garden grows back. Then

everything does.

Here we get the first iteration of the recurring “bloody bell,” a most certainly feminine symbol calling to mind both fertility and assault. The speaker is multi-orgasmic, a giver of life, an empowered Eve simultaneously naming and consuming whatever fruit she can find. Whether or not Eve is explicitly present in a poem, the speaker’s lovers take on qualities of the sacred. In “Water, I want you,” the speaker is “filled with something / that resembles you. I say, Be mine, // every time, but I know the shape that leaving / takes, half-loverly, half god.” In “Through a Glass through Which We Cannot See,” she joins in the tearing down of past mythologies to create her own in a basement altar.

We see a temple, then

sack it. I needed something, so I sang it.

O my Jupiter, magnetic war-dreamer who still

swings by & low—I couldn’t wear my red, red

storm on the bright outside for five hundred years.

By the time Mei-en’s final poem, titled “Canon with Wolves in the Water,” begins with the line “The world may end in fire,” we are convinced that it indeed might end that way. We move through a culmination of what we’ve been shown: the duality of half-things and of good and evil, and how “your dream of dying repeated” betrays our anxieties of a world ending in fire over and over, a destruction we would bring upon ourselves, a circular re-imagining of our shortcomings. And finally the speaker takes us past this chaos into a Biblical, unified elemental realm that she has interpreted her own way—that a “wolf watching water,” entranced by its own reflection, a feral Narcissus, is the truer, more complete end.

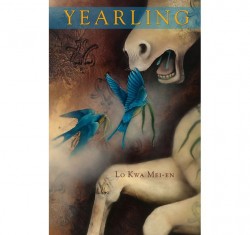

Lo Kwa Mei-en. Yearling. Farmington, ME: Alice James Books, 2015. 62 pp. $15.95, paper.