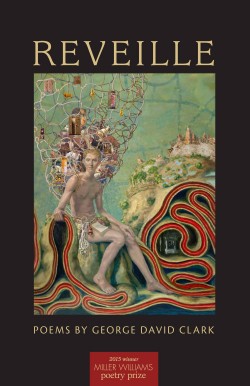

Each blurb on the back cover of George David Clark’s Reveille—winner of the 2015 Miller Williams Poetry Prize—identifies the surreal, dreamlike element of these poems, an element that is of our world, but not quite. Reveille, French for “to wake up,” is just that—a call to attention. It is also a view of this and other worlds that reaches past literal experience and into the realm of the imagined. But this is not a surreal book. We aren’t being asked to leave realism behind. Rather, the poet asks that we reconsider boundaries of our existence, of our realities, of our imaginations, and of our conceptions of religion and reverence. To do any of that, we must, first, wake up.

It’s fitting, then, that each of the four untitled sections in Reveille begins with a reference back to the collection’s title: “Reveille on a Silent Whistle,” “Reveille with Kazoo,” “Reveille with Reimbursement,” and finally “Reveille with Lullabies,” a poem which constitutes the entirety of the final section. Each “Reveille” calls to us in its own distinct, yet markedly musical manner. In “Reveille on a Silent Whistle,” the speaker refers directly to the reader(s) as “Sleeper,” implying, by appealing to us in a semi-conscious state, that our existence has perhaps, until now, been ill-defined—that we have erred in only considering consciousness as awareness. These poems ask us to consider that the full experience of reality might just now be “unfurling through the whisper-weight trumpets of light.” Indeed, every subsequent “Reveille” includes at least the concept of “sleep,” if not a reference to the reader as “Sleeper.” Reading Reveille feels, truly, like a lucid dream you don’t want to wake from, where “an angel spray-paints her wings,” where there are “suns we fail / to imagine,” and where “The bed’s / a clock gone haywire / or a compass / locked on heaven.”

If we consider Reveille as a lucid dream, we can identify real vs. unreal as one of the many binaries Clark’s poetry collapses. Take, for instance, the final line of “Reveille with Reimbursement”: “I’ve brought you the orange you dreamed of.” Clark is constantly bringing the dream world into our own, asking that we question the division between what we consider tangible and true, and what we consider fantastical. The stuff of Reveille is the stuff of both waking and dreaming: “fabrics made wholly of water,” “the long-tasseled / death-bonnets of children / we conceive but never/ bring to term,” “pink champagne,” “jaguar pajamas,” “leaf-scent / fragrant in a sweatshirt.” What, Clark seems to ask us, makes any one of these images more or less real than another? How do we decide what deserves to be worshiped?

Worship—especially as it collapses yet another binary: secular vs. sacred—is introduced early in the collection. In “Reveille on a Silent Whistle,” our existence is not a result of God’s will, but is a part of His own dreamscape, His own (sub)conscious projection. The passivity—or should I say, this tranquility—of existence is philosophically important for the collection as a whole. Nothing has caused us to be here. Everything has caused us to be here. Our being here is a quiet chaos, and Clark renders it in lush music and vibrant dream. No poem singularly captures this chaos, music, and reverence more effectively than “Reveille with Kazoo”:

From your overlong, even invincible sleep;

from the pink and orange moth-scales

that collect on your mind like a dust;

from the stately plush where you jonah

in a bottled frigate’s belly;

from this lopsided aerie of marigold sheets:

wake up.

“jonah” is not capitalized here, implying, I think, that anyone—not just churchgoers—can experience an escape from our world and still be resurrected (awakened) in this way. Religion is engaged with in an unpredictable, almost-subversive manner, as the poet seeks to explain or enter the sacred space in secular terms. Consider, for example, “Prodigalia,” wherein Clark embodies the persona of the younger son from Luke 15, detailing the revelry and near-animal lust the son experiences at leaving his home and his God behind. Clark reveals the insufficiency of the binary between secular and spiritual yet again as the poem acknowledges the spiritual deprivation of the speaker, but also revels in his physical lust and pleasure. Why, Clark asks, can we not find something to worship in all parts of this story?

In “Jellyfish,” the poet implores, “Tell me, / friend, is there an end / to revelation?” When in our development do we stop appreciating the wonders of the world around us? Childhood is often considered a holy time for this reason—our collective sense of awe is preserved while we are young. But does our experience of wonderment have to be limited to the past? Clark engages again with childhood and memory in “The Past a Sanctuary Staffed by Poltergeists.” This poem calls attention to the random nature of memory and apotheosis, to the fact that what is holy is what we deem holy. In this way, again, Clark concedes veneration of the sublime, but maintains that all we can do in this life is worship what is present.

One cannot read Reveille without noticing Clark’s handle on meter, on the iamb. These poems do not employ form for form’s sake—rather, they draw the reader’s attention to the ceaseless and inevitable rhythm of our world. Take, for instance, “Cigarettes,” the final poem of the first section, written in tetrameter. “She phrases it that way because pleasure / is complicated, more so perhaps than suffering,” does not read as doctrine, but rather, a musing made precise by the accompanying beat. “Interview Conducted Through the Man-Eater’s Throat,” too, plays not only with call-and-response, but also with an ABABCDCD rhyme scheme. “Whatever Burn This Be” eschews traditional capitalization and punctuation, instead manipulating repetition in word choice and subject matter, the effect of which is almost incantatory. There is repetition in reverence, and reverence in repetition. Clark’s use of meter, rhyme, and repetition—somewhat traditional tactics—is never predictable, never monotonous. Rather, the affect is “sonorous and redolent” of a poetic tradition that Clark intentionally manipulates to create his own brand of music. And these claims, this music being written about what it means to be human does not exist in a vacuum and, the poet seems to imply, neither do we. There is a current underneath all of these poems, propelling them, and us, into a more complete and musical existence.

Reveille’s religion is any world, real or imagined. The line between the actual and the imagined—between waking and dreaming—is explicitly addressed in the book’s final poem, “Reveille with Lullabies.” Clark writes: “Because there’s not enough rest in the world / there’s not and won’t be enough waking.” And:

There’s not enough blessed in the world

we wake in

But your chorus is vanilla

and its waves of fragrant vowels

bathe our names delicious in our ears

On the book’s final page, the author quietly reveals his core belief system. These lines are almost cooed to us, as the child in the poem is cooed to over and over again. Perhaps we, unlike the Sleeper, will finally wake up to the world around us. We’ll listen to every beat and measure. We’ll find worship in saying to ourselves, over and over: this is beautiful, and this is real. This is all real.

The University of Arkansas Press, 2015. 60 pp. $17.00, paper.