How to endure the unendurable? Perhaps it comes down to wit—keen intelligence cutting to the heart of things. Truth-telling wit may bestow power—however briefly—to the powerless. Think of the rawest blues song, the bawdiest limerick, Shakespeare’s Fool, the anthropomorphic mouse in the old poster, middle finger raised at the bomb looming over his head.

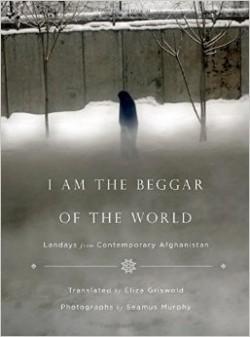

With the help of native speakers of Pashtun, and Afghan scholars of the tradition, Eliza Griswold has compiled and translated a book of landays — a two-line form of folk poetry perhaps five thousand years old — from Afghanistan. Her piercing, matter-of-fact commentary on the poems and their historical and cultural contexts, coupled with Sean Murphy’s stark and beautiful photojournalism, adds a new chapter to the ancient story of human indomitability.

Landays are typically sung, and in all but rare cases sung by women without prompting or occasion. Traditionally, they embody sexual longing or delight, and some of the most affecting of Griswold’s collection do so without explicit acknowledgement of war or oppression, mention of which would undercut the ironic humor of the landays. “Your eyes aren’t eyes,” begins one, setting up the immediate payoff: “They’re bees.” The second line concludes, “I can find no cure for their sting.”

In her commentary, Griswold situates the landay within a rigidly patriarchal culture. In this context, the landay is inherently subversive—dangerous and hidden in plain sight, yet elusive. Consider the poem that opens the book’s introduction:

I call. You’re stone.

One day you’ll look and find I’m gone.

A dozen one-syllable words, three full stops. By means of strong stresses (“call” and “stone”), the first line makes us feel the power of the poet’s need and her lover’s implacable response. The second line plays on “look” and “find,” embodying a hope whose futility the speaker can’t quite admit. Likewise, the permanence of “stone” rhymes with the finality of “gone.” “One day” issues a threat the speaker of the poem wills herself to carry out, but not yet.

A young woman who “called herself Rahila Muska” phoned this landay to an Afghan radio program. Unlike most of the “twenty million Pashtun women who span the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan,” Griswold explains, Muska had some formal schooling, but “poetry, which she learned from women and on the radio, became her only continuing education at home.” Because in Afghan culture “women singers are seen as prostitutes,” they sing in secret. After finding out Muska wrote poems, her brothers beat her. In protest, she committed suicide by self-immolation.

I Am the Beggar of the World documents the private, anonymous wars these singers wage, mirroring the wars that have ravaged Afghanistan for generations. In one of many stunning juxtapositions, a photograph by Sean Murphy shows five fighters on a barren piece of land, a truck in the near background, mountains in the distance. Four of the men stand, one bending over the fifth, who kneels on the ground, an automatic rifle to his right. Is the bending man helping the kneeling one shed his coat? Starting to treat a wound? Tying him up? Are they allies, or enemies?

The landay on the facing page reads:

In Policharki Prison, I’ve nothing of my own

except my heart’s heart lives in its walls of stone.

The photograph and landay play with lethal uncertainty and duality. The singer herself is not held in Kabul’s infamous Russian-built prison. She is alone with absence: her heart’s heart, her beloved, lives in the prison, and also within the “walls of stone” themselves, his being infusing stone. Because the singer can’t be sure her beloved is alive or dead, the poem supports and rewards multiple readings.

Wit infuses even the bleakest landays. For instance, confronted with “My lover is fair as an American soldier can be,” we notice the ambiguity of “fair”: is he just? Does he have a light complexion? The first line of landay plays on the variations and limits of American fairness, and the second line provides an unambiguous reading: “To him I looked dark as a Talib, so he martyred me.” The singer is revealed as a voice from the grave and the lover, fair or not, soldier or not, her killer.

In her selection of these landays, Griswold works to explode the notion of Afghan female helplessness. These tough-minded, heartbroken, defiantly funny poems reject tail-swallowing irony and narcissism characteristic of some contemporary verse. Like any living tradition, the landay is simultaneously timeless and of-the-moment. It does what all poetry attempts to do: sing what’s most fundamental in human existence.

Translated by Eliza Griswold. I Am the Beggar of the World: Landays from Contemporary Afghanistan. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2014. 149 pp., $24.00, hardcover