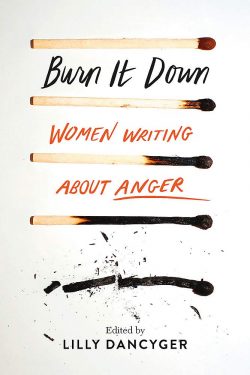

“Throughout history, angry women have been called harpies, bitches, witches, and whores,” Lilly Dancyger writes in the introduction of her new anthology, Burn It Down: Women Writing About Anger. Written by a diverse group of angry women, the twenty-two essays in Burn It Down confront the long history of women accused of being dramatic, hysterical, crazy, or hormonal for expressing anger and forced to swallow their rage in order to be viewed as composed and respectable ladies. Women are angry about so many things. They are angry about widespread violence and sexual assault, being stripped of rights and agency, being talked over, told to be quiet, or not taken seriously, and so much more. “Every woman I know is angry,” Dancyger writes. Burn it Down splits open women’s anger to reveal the ugly, uncomfortable inside and gives women a space to rage.

Many of the essays in this collection address the gendered nature of anger, who is allowed to express it, and how women bear the burden of keeping the peace. The writers talk about not having a space to release anger, and several speak of denying they ever felt angry so they wouldn’t have to confront it. Dani Boss’ essay, “On the Backburner,” describes how as a child she learned that the place for women’s anger was in the presence of other women. She watched her mother trade stories of frustration and rage with other moms and noted how often she heard, “phrases like, ‘I wish I could have said… ’” (157) On the other hand, Boss writes that her father openly raged, and she learned that as a girl it was her job, “to keep the peace through [her] work and [her] silence.” (158) Reema Zaman’s essay, “My Name and My Voice,” also speaks to the expectation for women to bare the weight of a man’s anger; “I’ve been taught that men of any kind, be they our abuser, father, or partner, are our mystery to solve, our duty to abide, our pain to nurse, our responsibility to care for, our child-master to defer to.” (140) Women are taught to be nurturers, first and foremost, even if it means they must sacrifice freedom, safety, or happiness.

Several essays discuss anger in relation to one’s identity. Shaheen Pasha describes her experience being a Muslim woman in America and her anger arisen from trying to navigate these two identities with pressure from both sides to choose between them. Samantha Riedel explores her relationship with anger before and after gender transition, writing how she exerted anger and aggression as a child in order to “perform masculinity in the only ways she knew how.” (72) Monet Patrice Thomas discusses the intersection of race and gender, the angry Black woman stereotype, and how suppressing her anger is an act of self-protection. When a man sexually assaulted her, she thought, “What expression could I conjure that would not encourage him further but would remove me from harm’s way?” When a police officer pulled her over and put her in the back of his police car, she “fixed [her] face, this time into a picture of innocence.” (32) In both instances she felt fury.

The collection also talks about how women’s anger can become entangled with other emotions, as a result of how women are socialized to behave. Marisa Korbel’s essay, “Why We Cry When We Are Angry,” talks about when anger produces physical tears, a frustratingly feminine response that becomes easy for others to dismiss; “When angry, men are much more likely to act out physically in aggressive ways. Women are more likely to cry.” (67) Erin Khar explores how women’s anger is placed back on the woman, taking on the form of guilt. “Anger in a women is akin to madness,” Khar writes. Khar lists things she has been called when she is angry, including “irrational,” “unstable,” and “in need of help,” (97) to reveal how these labels cause women to internalize and twist anger into feeling guilty for their behaviors and emotions.

The essays in this collection are bold, harrowing, honest, and cathartic. They depict a wide range of women’s anger, scorching hot and taking a stand. Other essays include Lisa Marie Basile’s piece on how often women’s physical pain is ignored, belittled, and left untreated. Meredith Talusan writes of doubting her own intelligence when a male classmate contradicts her in an area she has more expertise. Marisa Siegel writes of worrying her father’s oppressive anger would be genetically passed on to her son. Rowan Hisayo Buchanan examines how hunger leads to anger, and Dani Boss explores anger and menopause. Melissa Febos and Nina St. Pierre describe being angry, hormonal, teenage girls with a reason for their anger.

Perhaps the most satisfying moments in the collection are the multiple echoes that women’s anger so very often justified. “My anger signals the presence of an injustice,” Reema Zaman writes, “Rather than being shameful, my rage is noble.” (141) Erin Khar says, “I have a right to be angry.” (101) In a society that gaslights, silences, and dismisses women, this needs to be said. Each of the women in these personal stories has reason to be angry, and they are all justified.