To dissect lions

You need lightning

-Julio Cortazar

Find the seam. Underneath the slipcover, the hospital pillow is stuffed with some kind of synthetic goose down. Wonder where it is that they find synthetic geese.

Posit: “Maybe they bred a goose with a synthesizer.” She will laugh then cough or cough then laugh. “Did you know,” she will say, “that jackalopes can only mate during an electrical storm?” Check the color of sky outside while she rubs dry-cotton static from the bed sheets into her hospital gown. In order to ground herself, she will hold out a hand and say, “Touch me.”

Keep your distance. Ask: “Is it that a jackrabbit and an antelope have to have sex or can only jackalopes beget jackalopes?”

“Tell me about the food we’ll have when I make it out,” she will say. Think exotic, mythical. Say: “Unicorn-on-the-cob.” A “turducken” is a delicious animal that’s part duck and part chicken and part turkey. Note: If she instead says, “if I make it out,” go ahead and touch her. Take the shock.

Required tools:

a. Scalpel

b. Scissors engineered for precision cutting

c. Skinning knife

d. Small pry bar (for nails, staples, glass eyes)

One explanation: Jackrabbits are vulnerable to a disease called Shope papilloma virus which can cause keratinous carcinomas—tumors, antler-like—to sprout from the body and head. At the start of all of this, she asked, “Will there even be enough of me left that’s worth loving?”

Tell her survivor stories. The Lion and the Mouse. The Three-Legged Bear and the “Bear Right” Sign. You once heard of someone who went through both surgery and radiation therapy and came out even better than before. Explain: “Something in the chemo changed her hair color. Not only did she come out cancer-free but she went from a blonde to a redhead.”

Outside, the wind is blowing currents through the grass. The halogen lights in the hospital parking lot are timed to go off when visiting hours are over, so you say your goodbyes under the emerald glow of her IV machine.

Walking to your car, think: Jackalopes are like rabbits’ feet. You only see the unlucky ones.

You will be constantly measuring, constantly cutting. Measure the length of your steps to the car. Measure backwards from the point of the nose to the corners of the eyes. You’re doing just fine.

It is the responsibility of The Anti-Taxidermist to step in now that The Deadbeat Husband has walked out on her. Bring flowers picked from her neighbor’s garden, thus brightening her room as well as leveling the playing field back home.

She will ask, “How is your son?” This question is best left to advanced students (short answer: “Still living with his mother.”). Practice extracting yourself from these situations.

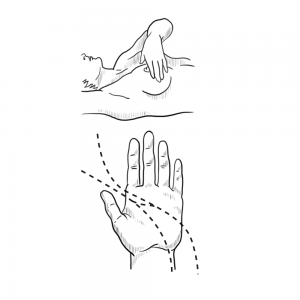

It is acceptable for the two of you to have a history, so long as neither one uses the current circumstances to his or her advantage. She will allow you to stay in the room while they make preliminary preparations for the OR, which include lifting up her top and using a permanent marker to draw a dotted line showing where to cut. Her eyes, just over the raised paper gown, will be on yours throughout this process. At this point, The Anti-Taxidermist must separate all sexual thoughts from his body (a scalpel or skinning knife is recommended).

“I’ve been thinking about hopeless romantics,” she will say after a red Jell-o lunch. The Attractive Day Nurse is bent over the edge of the bed scribbling something on her chart. Note: Even your feelings for The Attractive Day Nurse must be buried in mothballs and stuffed deep into your subconscious. Even in your dreams, you are in a constant state of pulling your body off of someone else.

Your precision scissors, curved like a child’s ear, should fit comfortably into the saddle of your thumb like it was a natural extension of your body. Slowly work your way around the edges. “Now that Harry is gone,” she will say, “I’m beginning to think that I was the hopeless half.”

Tell stories all afternoon.

Ask: “Did you know that my father had a hunting cabin?” She will say, “You mean the double-wide that sat just outside the city limits?” Your father called it a cabin even though you knew it wasn’t true, and the only things he ever shot were overflow pests that made it across the freeway. There was pigeon shit on the front steps and cerebral masses of rat babies in the couch.

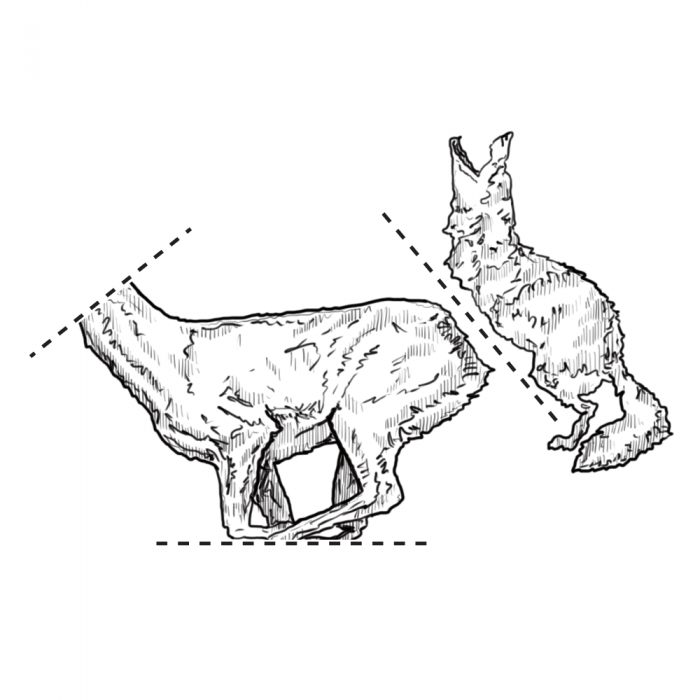

But she doesn’t know about the time when you were thirteen and went walking in the woods behind the trailer. Tell her how you once found a deer—a doe, you think—and once, a coyote. Do not tell her about the cavity in the coyote’s belly or the frayed rope of the deer’s neck.

Always keep a safe distance from your subject by using the correct tools and proper safety equipment. Nostalgia might be contagious but you can share more than just memories with the dead.

Do not tell her about how you found the deer and coyote on the same trip, how someone (your guess, a group of teenagers) had wrapped the legs of the coyote around the torso of the deer. This is not the place to discuss pantomimed acts of love.

Also omit: The morning light falling slant on their matted coats and how it almost looked romantic. Remember how you distracted yourself from the sight of it by coming up with names for their mythical progeny. Coyoteer. Deerote.

Also omit: The unsure laughter of teenage boys. You were a coward back then for not pulling the two animals apart.

Self exam: Why did the two of you ever date in the first place? Was it:

a. Post-traumatic stress from your marriage.

b. Pre-traumatic stress from hers.

c. Your mutual friends calling it “a good fit.”

Half an hour before the surgery, she will start to get scared. “Just think,” she will say, “the next time I introduce myself to a guy as ‘single,’ he will think ‘Yeah, just like your mastectomy.’”

Take a moment to calm yourself before the first incision. You have been properly prepared for this situation. Your breathing should be even. Your hands should not be shaking.

Note: The hand can be separated into three parts: the utilitarian, the gesticulative, and the sensory. (Not counted: the lifeline.)

Gesture: You’ll be fine, you are loved, etc., etc. Make a gesture that travels backward through time, referring to your history together, something that says You know what I mean?

Say, “Did I ever tell you the story about The Grophen?” She will say, “You mean The Griffin?” Say, “Grophens are much rarer. They live for a hundred years. They burrow and court in the tall grass and once they mate, they grow wings. One look from a Grophen is enough to cure the deadliest disease, which is why hunters all over Wyoming keep mirrors in their pockets. Because if you are not sick yourself, the least you can do is try and reflect the Grophen’s gaze in some other direction. And if two hunters each have a mirror, there’s a chance they can keep the gaze reflecting back and forth between them long enough to get it to where it can be of some use.”

Two attendants will come to wheel her out. Decide that she has never looked more beautiful than the moment when the catch is released, the bed drops back, and her hair fans out across the pillow. She will say, “Last chance to cop a feel.” If she does not say, “Last chance to cop a feel,” you should make the suggestion for her. The two attendants (both women) will glare.

The Anti-Taxidermist must not believe in any invisible healing powers. Homework Question: Does chemo count?

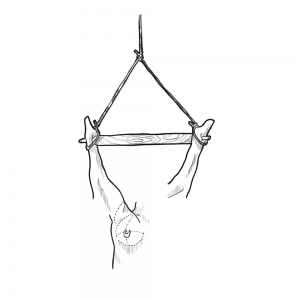

Grophens do exist. There is one sitting on a homemade, wooden mount in your father’s hunting cabin (double-wide). Its wings are extended, held open by hidden bits of wire. Note: Its eyes have been replaced with black marbles.

You’re doing just fine. Use the blunt-nose pliers to wrench free any doubt.

The waiting room comes with only one step: Wait.

Your father on the Vietnam War: “We walked. We waited. Then Wendell began to tell a ghost story. Then his arm was gone. Then it was over.”

You used to be better at make believe. Remember how your son liked it when you changed the endings of his bedtime stories so the prince and the princess “strode into the runset and lived happily for never laughter.”

Phantom limb is the sensation that a missing body part is still attached and functional. Symptoms can include perception of pain in the vacant area, feelings of weight, and abstractedly reaching for something with nothing.

With the flat edge of your scalpel, gently lift up an edge of the hide. Underneath the cured skin you will see a polyurethane frame. This is the reason all mounted animals feel lighter than they should; they are empty on the inside. Homework Question: Does the Phantom limb feeling apply to all body parts?

Pull the picture of your son out of your wallet. Note: The picture should be folded, with the crease starting below his right armpit and running out through the top of his head.

A middle-aged lady sitting next to you will notice the picture. She will say, “I’m sure he is going to be just fine. The doctors here are very talented.” (Long answer: “My son is living with his mother. He has started combining my Christmas phone call with my birthday phone call. Along with my child support payments, I send photos of myself, circling in permanent marker the features of my face that are similar to the features of his face.”) Add another fold to the picture and place it back in your wallet.

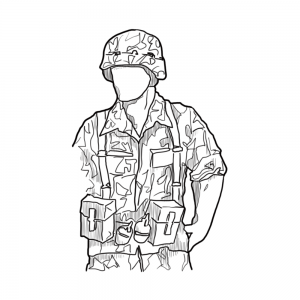

At least your father had a uniform. The Anti-Taxidermist must provide his own work clothes. It has been two and a half hours already and she still has not reappeared from the Operating Room. Dressed the way that you are, it is unlikely that they will tell you anything.

Your father claimed that he never killed anyone in the war, but this man also lied about the things that he did kill (example: The Grophen). Remember the first time he handed you the hunting rifle. You were thinking, “I will take it, I will take the shot. But I will miss on purpose.” Wonder if you had a similar plan in mind when your ex-wife asked you if you had been cheating on her. How you lied and said, “Yes.”

Breathe. Aim. There are nightmares where the enemy rises dripping from rice paddies, holding their guns in their one good arm. You were going to miss on purpose, but no matter how hard you try, you keep missing at missing.

Posit: Is it possible for the dead to come back? What will happen when the sutures are opened (use scissors) and the mounting bolts are unscrewed from the feet?

Refer to your father as if he’s still here. Refer to your son as if he’s still here. Touching the empty space, your brain sends you the old, familiar signals.

Her operation is successful.

It’s a cross between a gopher, a pigeon, and a rat.

Marvel at the flawless, nearly-invisible stitching. The Anti-Taxidermist should feel guilty for looking too close, for trying to find the point of division.

Try to avoid excess incisions. The less you have to repair, the better.

Wonder what happened to the unused parts, the stuff that wasn’t combined to make up the final product. Posit: Somewhere behind your father’s hunting cabin is an unmarked grave for a wingless pigeon.

She will say, “They’ve still got my tumor back there in a little glass jar. They say it’s pretty friendly, and if you put your hand against the side, it will swim right up to your finger. They offered to let me take it home, but I was worried it would get lonely. Better to let them keep it here, where it can make friends and get lots of exercise.”

Complete separation is the ultimate goal, each animal returned to its natural state. Homework Question: Do you want her all to yourself?

She still will be dream-talking from the anesthesia. She will say, “I know there’s no evolutionary proof and not much hope for griffins, but if they just gave a lion and an eagle a chance to find some common ground, who knows? Maybe they could make a baby after all.”

Decide you cannot be a griffin. Griffins mate for life. What’s more, if one mate dies or disappears, the other will spend the rest of his days alone, avoiding all other contact, ripping to pieces any other creature he might come across.

Note: There is still a chance that they will have to take the other breast.

Plan your escape from the Post-Op ward. Use bolt-cutters to sever any wires you come across. Once freed, the wings will collapse back in on themselves like Japanese fans.

This time, when the doctor comes in to check on the sutures, she will ask you to wait outside.

Stand at the door like an expert, like a licensed Anti-Taxidermist awaiting a professional consult. Measure the length of your steps from one side of the hall to the other. Measure the tone of voices inside.

There are options. She can choose plastic surgery or go for an external, removable pad. In the meantime, the front of her gown will remain lopsided. She will say, “People are either going to feel twice as guilty or half as guilty for stealing a look at my chest.”

Using your precision scissors, cut a dozen yellow roses from her neighbor’s garden. Using your stainless steel tweezers, separate each petal from the bud. Come back that afternoon to scatter these across her hospital bed. Tell her that you have only brought back the “He loves me” ones. Note: Her rolled eyes. The sound the petals make on her paper-thin sheets.

Think about the men that will come later, and how you wish you could castrate them all (use needle-nose pliers). When they picture her naked, they will be imagining away more than just clothes.

Wanting to change the subject, she will ask you about your son. Talk about her chances instead. Homework Question: What is the likelihood they will have to operate again? Talk about your own family history of disease, and the tacky legacy each generation leaves behind.

Measure: a father’s disappointment.

She will say, “Tell me about The Lobster that fell in love with The Swiss Army Knife.” She will say, “Tell me about the animal that was shot and skinned by the hunter and lived, then watched herself be mounted on the hunter’s wall.” Say, “She grew another skin and next season the hunter mounted that one too. And the same thing happened the next season and so on until his world was filled.”

Leave out the sad parts, the metaphors and allegorical tropes designed to illuminate life lessons in a time of loss. Measure backwards from the corner of her eyes to the base of her spine. If it doesn’t belong, cut it.

Tell her what your father once told you: “Over five thousand American soldiers lost an arm or leg in Vietnam to land mines, loose bombs. The medics wrapped the severed end in gauze then helped the soldier shift his weapon to the other side. Moving through the ranks, I’ve seen artificial limbs made of broken pipes, bamboo, and even old artillery shell casings. Some soldiers, like Wendell, came home and took a hook for a hand. Five thousand empty arms and legs pieced back together in plastic or aluminum or sometimes not at all. What you may not know is that while our veterans were being patched up with prosthetic limbs, there were people combing through the jungles of Vietnam looking for body parts so they could patch them up with prosthetic soldiers.

“It’s true, just like a soldier here could get an artificial arm, somewhere back east, his real arm was getting an artificial soldier built around it. The arm had to do its best to get used to the prosthesis, and it usually was never able to completely hide its limp, but the artificial soldiers they’re making these days are remarkably lifelike. And they’re not just doing this with limbs. There have been prosthesis constructed around fingers, ears, even a solitary eyelash that was lost at the fall of Saigon.”

She will ask you why you are telling her this. She will be scratching at her stitches in a way that will carve into your chest its own hollow hurt.

Note: You are telling her this because you are afraid of the artificial Anti-Taxidermist, the one built entirely out of prosthetic material except for this story of your father’s that you never got to pass on to your son.

Drive her home. She will roll down her window and adjust your side mirror so that it’s reflecting back towards her. “Just in case,” she will say.

You never believed in fairy tales, not even as a child. You kept wanting to know how the hunter could cut open the wolf’s belly and have Red Riding Hood and her grandmother spill out unharmed because in those stories, only the ones who are supposed to die will die. And afterwards, why did they have to fill the wolf’s belly back up with stones?

Measure: Chest to tail. Cut: Between the shoulder blades. Pull off the wings.

Another word for these kinds of stories is yarns. They must call them that because they can be raveled back in.

You are almost at her house. She will be holding her seatbelt away from her chest with both hands, still weak, struggling against the tension. Squeeze her knee. Brake soft.

Say, “Your neighbor’s garden looks terrible.”

Remember the only real date that the two of you shared, how it ended back at your post-divorce apartment with you, the nervous surgeon, unsure of what should be removed. Remember how her bra snarled in your hands and how she hunched, helping, as you kissed her again and made a joke about needing to get your tools. At the time, it seemed like nothing in the world was as secure as the clasp of that bra.