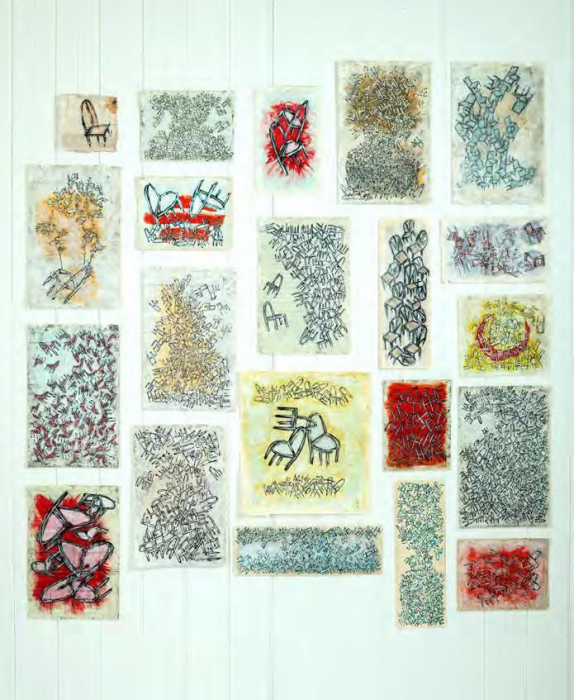

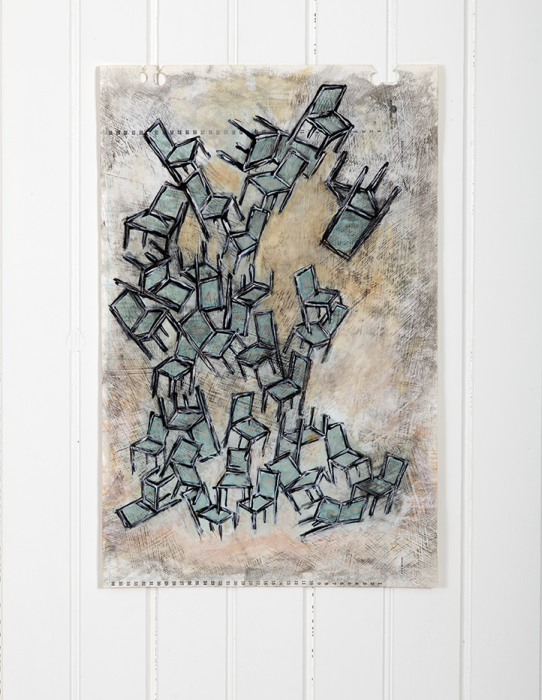

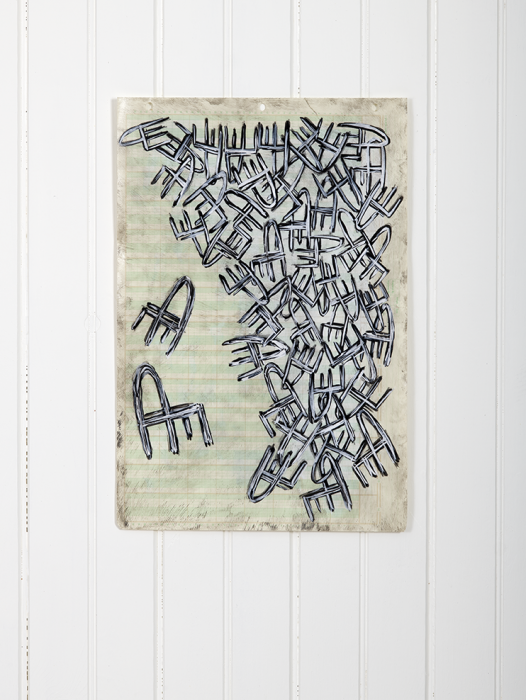

In the traditions of many, chairs are set and left empty for a patron, set for a particular saint a religion calls for in our most specific of moments, or for all our families’ departed—believed to be obliged to arise to our occasions. As a child I suspected there’d been too few of them willing to show up for all the requests being made of them. I thought maybe most of them we prayed to and for had never wanted to show up in the first place. Yet I remained believing in ones who try at moving on to better than us and I left space in our empty chairs, empty. I painted my first image of a chair on a cold morning in late 2019. We’d been going through another difficult time. Our lives in a way blown up again only months before the whole world would, again. As I listened, watched, and tried to find new ways to work and be, I painted chairs. I used ink instead of paint because it’s what I had on hand, and because I needed to breathe well enough in my small workspace. As a pandemic took hold of time, I went on to paint hundreds of chairs and began writing to each one as an entry in a record. I gave myself permission to write at the cadence of how my mind has worked since childhood—a way I’ve had to train myself away from. The conversation between the words and ink and how I see the past collide into an indictment of my memory to become a broken recollection, stacked over and over. prepositions for elijah is twenty collections of words in concert with twenty paintings—as devotions to saints of absence.

for when triggered sounds of animals came down a path towed in a line and a single source cicada pealed across to a tree-to-tree switchboard in front of a man you’d known named elijah and a seventeen-year swarm of echoes responded in eucalyptus rungs he’d wished to believe wouldn’t burn in our lifetimes but had in our lifetimes and our elijah this elijah your elijah a man you’d known awoke to what none had predicted a brood so far west off calendar even of probable stragglers thirteens or seventeens broods so fast then the eucalyptus had burned all the next seasons until no more seasons a land could die again plague bugs shouting over their own accord the record shows as loud as when this elijah had pinched them from a tree as a child then it had been called brood i i 2 been predicted again by a twenty thirty if our elijah would have made it that far when he hadn’t you’d wondered after how he’d pinched fore-wing between thumb and his forefinger a trick god told him had been to breathe warm on a locust’s back some called them locusts but grass-hoppers too were called locust and elijah wondered how people settled on what to call a thing a flower for making and a flour for baking sounds to him all the same otherwise cicadas shook in his fingers if he didn’t blow on their heads until they’d rip their own wings off elijah’d told you how he’d slid silk thread under hindwing their abdomens thick made a nice little groove below the thorax made for a perfect kite toy boy torture elijah’d been careful not to bind the trochanter too tight before he’d even reached an age to do worse he’d begun gathering their empty sleep skins stuck to the side of an oak tree gathered into his fon zee t shirt pulled out from his waist as a net delicate as you’d need to be to detach them from bark whole elijah created a guideline in his mind to keep the delicate tarsus from snapping off the labium after they’d held themselves to bur oak stragglers from another brood probable always more north more west strong enough to split their backs open to escape as wet soft angry adults free he’d built a tower of their baby skin shadows as a child the record shows elijah showed you how he rubbed his finger tips on sharp edges of their empty skins to determine where to hook them to one another into a tower of lifeless beginnings and elijah built them into a spiral cone seven inches in diameter at the base to reach seven-teen inches tall the record showed the last time he’d measured them he’d hid them under a milk bucket with a rusty sad iron he’d found dug out of the ground put atop to keep the bucket down and left it all behind at the base of the poplars facing north east in their field kept everyone else from his accomplishment that year but you he could lift up the whole tower by only the top carcass of what’d been a baby bug’s skin whole and elijah fixed their tarsus tight unyielding until near the end when elijah got his call transmissions from cicadas peeled them among eucalyptus now this far west torn at right angles to last wishes all quieted under and over marks elijah’d made until it became an accepted fashion every one ready to share their towers of skin anyone could have even asked where’d you get yours and elijah’d never told the record shows without a confrontation most who’d known how much loudness cost to past shame compared to all they had to lose elijah had nothing to lose a plague shook all hard until you ripped your own wings off less a swarm of destination than when elijah devoured your single hum.

for when they’d been listening a reuben had wanted to build it all by himself with his own hands do it all on his own even the electric all sort of things he knew nothing about with the last of all he’d had so you could insert our spirits in thy neighbors he’d like to say about the house he was building the grand porch by which to receive them but the house of reuben burned right before the porch could be finished just a cement slab where you carved rufus in your clumsy hand into the wet concrete left after the mister coffee melted down caught fire only a few months after you’d move in from the single wide you’d been at school he’d been painting a parishioner’s home your mother at the bank and your brother dead from that cracked head he’d never even gotten to see the cement slab how that porch would have run down the whole length of the home to open to the world to receive all of their spirits all of it was gone after that day everyone was gone and mister coffee been left plugged in along with your mother with the banker always with the bankers in small towns bankrupt promises before your father’d been able to open to anyone the record showed your father a reuben which meant to behold a son and you a rufus which meant red-headed ruddy moved on too into buildings with shared walls your ceiling another’s floor one way in one way out where no spirit could follow us the first reason why your father gave you about giving up and you used to say you couldn’t remember a single face of a single neighbor like this reuben wanted to forget except you do remember the neighbor who fell through a stairwell a concrete step crumbling under his foot you watched his face as he fell but not the name the record shows you couldn’t remember his name but you’d heard the neighbor sued the property management company to pay for him having to live in a wheelchair for the rest of what was left of his life and there’d been the girl in the bikini with the body of a woman the only body of a woman you’d seen in person except your mother’s she’d walk five blocks from the public pool on tuesday and thursday afternoons in only a towel the only body of a woman besides your mother you’d already begun forgetting the fastest way to forgetting is trying to remember if you’d only ever ate one meal in those years with your father in those single rooms neither of you bothered to call a home for seven years where you can only ever remember one sit down meal at the end in the record from all those seven years how couldn’t there have been more rufus you can’t even see your father saying a word any longer and you wouldn’t say we ate the same thing over-and-over or you wouldn’t have said in the record we ate only once in the end you hadn’t been able to recall how silent over-and-over one sunday meal became all them neighbors never inserted with his spirit to stand in for the rest of all the other dinners you remember the same roast cut stewed in a crock-pot paper packet spices another one powdered for gravy brown and serve rolls mashed potato flakes you’d never lost your taste for iceberg lettuce pre-shredded cheese from a plastic bag reuben your father whether by moral or survival provided minute conveniences for you back then like a miracle whip you used to make your own thousand island every sunday two to one miracle over catsup plus a spoon of sweet relish only a pinch of salt.

for when instead how it had begun an esther never thought she’d ever get more than a week or two ahead again better than the weeks behind it hadn’t been enough to get by on sleep lost over more owed past due and come autumn been another way to say fear for when more still were looking for chances to be beautiful for a last time when anyone could tell how miserable it could be to be alike this esther’d said a willow takes more to requite itself to soil esther said things like that said words like requisition to mean compost loved making things she’d come to know as her own and our esther in the record you’d seen continued on rats collect wet leaves in late winter into a wet spring esther said they last long years she’d said not like others’ deciduous leaves she’d meant rise early and you’ll see a will of them for when then the word mischief’d been the accepted term for a gathering of vermin this esther invented will for her pests she’d said in the record a will of them drag willow leaves from our gutters dance along our fence tops esther sang on into privet dark corners she’d end her palaver with to suffer a wet mess of medicine to her neighbor who’d been named miles who’d slam his door on her to acknowledge the price of heat this miles chopped thunder and split lightning esther listened from her kitchen to his volume of rage then when he’d go quiet start stacking his patterns between hemlock trunks in his very own grove miles wouldn’t ever take them hemlocks down even if they could fall on one of our houses esther asked miles and he’d said especially when they can and he’d go on and build cords all shapes and sizes between his trees miles read the cross sections of fir all he could afford to buy that year mixed with an old stash of ash miles preferred walnut patterns to make maps a guy told him two seasons ago of a free fall of walnut and he’d been too late again as he lie in bed and couldn’t sleep damn esther’s wind chimes pierced past his dying eardrums he’d leave hearing machines on his bedside stand whenever there’d been wind and there’d always been wind then for when his pillow couldn’t force her peals away he’d invent cord patterns of wood in his mind drive longer miles for cheaper loads he couldn’t afford to get hung up on a cost of a future fire with nothing left to explain his anger like everything else in the world is something to be mad at and back in twenty nineteen an eclipse of moths flit a monstrous white shadow cloud over a culvert on the two lane twenty at the blind curve he parked a quarter mile on to walk back and the moths took him right to a black cottonwood fall two thirty footers eleven and thirteen in girth each sharing the same root laying on their sides wet in the ditch moths flitting around they had a deep dark core made beautiful stacks a design her wind chimes had pierced into his mind between his hemlocks now and ever since then miles kept an eye out on ditches kept the winch on and a case of flares where wind whipped a road hardest in the corners believed those moths had been the ones to show him and the more miles held still with his cuts stacked elaborate as music he’d read hard winters from decades ago in cross-sections and one hundred years in a fir etched rings left fitted between the trunks of his own grove he’d never cut told esther his neighbor without telling her let them trees kill us in our sleep he’d whispered to his cords of wood walls mazes and miles held still quiet but it’d been esther he’d whispered to just enough for her to hear when he knew she was behind stacks on another side where she found her own music in his wood she’d found his cords arranged magic and he’d know when she’d be there on the other side listening miles whispered every ugly child beautiful when that’d been the beginning of them in the record when he’d whisper even when they weren’t there in the end huddled together a consequence of warmth not a will or a mischief.