Piping Plover Charadrius melodus photgraphed by Carmen Ostermann

A balancing act between creation and destruction, Carmen Ostermann’s wondrous porcelain sculptures give form to ineffable feelings: the tension between desire and time, the interconnectedness of the natural world, and the responsibility to witness through fear. ‘I am one of those animals’ asks us to consider the position of the viewer in relation to these endangered birds, entangled as they are in masses of coral, the clay itself, and our human gaze. Art Editors Heather McCabe and Cat McMahan interviewed Ostermann about materiality and metaphor in the face of ecological crisis:

Cat McMahan: Can you walk us through your planning process for these sculptures? Do you already know what details you’re going to include when you start out?

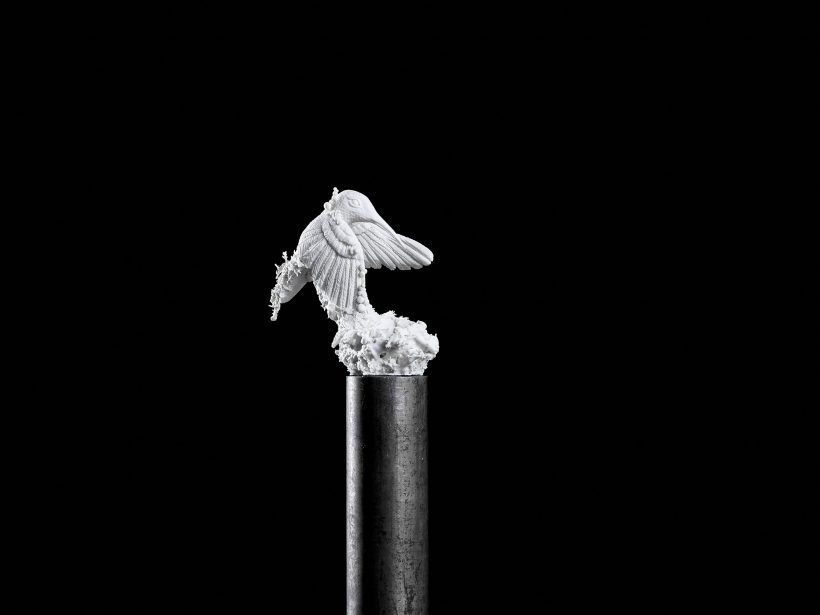

Carmen Ostermann: I plan and create works based on ornithological studies. I select an endangered bird and spend the initial part of my process researching and attempting to truly know the physical form, habitat and lifestyle of the species. After giving time and attention to listen, look, and learn about the bird, I begin illustrating various compositions of a three–dimensional piece. Once I am confident about one of the illustrations, I make a rough sculpture. When doing this I construct the work solid and search for the essence of the bird. I am looking for a gesture that evokes liveliness and a form that is tragic. I create a sensation of drowning by showing only the extremities, the tip of a wing or the end of a beak emerging from the overrun surface. The bird’s body parts are often twisted as if they are simultaneously being pulled into the earth while the nodes smother them. Once I have completed the animal aspect of the work, I delicately add growths to their surface. In every piece the birds are encompassed by hundreds of nodes kindred to fungi, coral, and foliage from their habitats. Inspired by ecological succession these barnacle structures sprout from the bird, pulling them down in flight, and consuming them whole. Ecological succession is what succeeds and claims a space after species destruction. In many ways this natural process is the in-between space in which death is the source for new life; destruction and beauty are existing simultaneously.

Glow Throated Hummingbird Selasphorus ardens photographed by Jake Holler

CM: What motivates your choice of material for a project? For a series?

CO: My ceramic work is made from a white opaque porcelain that highlights the intricacy and fragility of humanity’s relationship with nature. Clay is heavy but also delicate, and if the making process is not timed properly, it will crack and break. The waxy surface of the sculptures are an alabaster colour akin to that of a bone. Similar to coral bleaching due to rising sea temperatures, the sculptures appear as if all chroma has been drained from them, foretelling an ode of what may come to pass. Many of the birds I sculpt are migratory and spend time on seashores. I visually reference threatened corals that reside in their habitats through the sculptural nodes emerging on the bird’s surfaces. The nodes are organic, budding and bursting with infestation. They are proportionally smaller than the birds, creating a feeling of decay, ultimately inducing the shape of the sculpture. At times, I will incorporate materials from nature into my installations such as a piece of a tree that has clearly been extracted from the woods. This references our consumption of resources as well as habitat loss. I also utilize enclosed objects in my installations, such as glass cloches or cages. I use containment to draw attention to what we choose to preserve and question what we should. Frequently we are attempting to save animals, cultures, and practices that are on the brink of being completely lost. In this way their preservation and exhibition is a last resort and reflection of poor judgment. I am eager to seek and create methods in which we can also support what is currently prosperous in order to prevent future endangerment.

Caged photographed by Jake Holler

Piping Plover Charadrius melodus photographed by Carmen Ostermann

Heather McCabe: Do you feel any tension between the mutability of porcelain in its unfired state versus the solidity of the fired material?

CO: I feel tension throughout the entirety of my making process, from the unfired to the fired, as there is a constant possibility of collapse. By using clay, a material that stops and survives time, I am able to create moments of suspension and permanency. I ask the audience to observe acts of destruction and question what is worth preserving. The birds are grounded in flight, weighed down by the trauma of environmental destruction, and suspended in a state of being devoured. The nodes visually overtaking the birds are a direct reference to humanity’s incessant extraction of resources from the environment that has led to devastating habitat loss and the demise of the species the sculptures are embodying. I experience tension through the acts of destruction that benefit our species but are the downfall for others.

Martha Passenger Pigeon Ectopistes migratorius photographed by Carmen Ostermann

Whooping Crane Grus americana photographed by Jake Holler

Tree swallow Tachycineta bicolor I photographed by Jake Holler

HM: Your sculptures strike me as clearly narrative—deeply engaged in a kind of story-making, especially given the title “I am one of those animals”. Do you feel a narrative pull when you’re creating? How does the title compliment or complicate the sculptures themselves?

CO: When making, I contemplate the narrative of the species I am engaging with. I wonder about the lives they lead, about their stories. I consider how their stories are intertwined with my own and how all these stories intersect with destruction in their timelines. We are currently experiencing the Anthropocene extinction, the ongoing sixth great mass extinction in which a large number of living species are threatened or eliminated entirely due to environmentally destructive human activities. Considering that this is the first biotic crisis “caused by an animal and not by a natural event” and that I am one of those animals has strongly steered me towards my current practice (Foer 77). Birds have been hit hard as their population has lowered by three billion since the 1970s, that is approximately one third of all birds. They simply cannot survive the swift alterations humans are inflicting in their environments. “Since the 1500s, humans have entirely eliminated more than one hundred and fifty bird species. No other class of vertebrates has suffered more extinctions” (Nijhuis 60). The title, I am one of those animals, reveals an essential kinship between us, humans, and other species. It acts as a pathway to empathy in hopes to lead to reciprocity. The narrative aspect of the title creates a relatability that connects viewers to the work and nature.

Foer, Jonathan Sanfran. We Are The Weather: Saving the Planet Begins at Breakfast. New York:

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019.

Nijhuis, Michelle. Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction. New York: W. W.

Norton & Company, 2021.

Gunnison Sage Grouse Centrocercus minimus photographed by Jake Holler

CM: This series has a clear and vibrant connection to the danger that many bird species are in as climate change occurs and habitats are destroyed. How has creating these pieces affected your own personal relationship with nature and its preservation?

CO: Creating this work has allowed me to spend time reflecting on humanity’s relationship with nature and its preservation. My work demands a considerable amount of time to build. While constructing I am humbled in thinking of the complexity of the animals, flora, fungi, and coral I make. As someone who lives in a city I have noticed that engaging with nature takes effort and is not always accessible. I make work that’s attention to detail requires visual engagement and consideration of animals and plants people may not have access to or may not have taken the time to notice. I use my attention to blend art and science and in doing this sow the development of intimacy with the natural world. Recognition of beings other than humans as well as our reliance on them for our own existence has brought me on this migratory journey. I am constantly thinking about humanity’s role and the part I play. I strive to listen and wonder deeply, in hopes that I can follow my instincts and make good choices in relation to not just myself but the entirety of living beings.

Glow Throated Hummingbird Selasphorus ardens photographed by Jake Holler

HM: The theme for this issue of The Journal is “Collapse: : Rebuild”—I’m curious what kind of relationship you see between this theme and your sculptures or perhaps your art practice itself. What does it feel like to make art in the present moment?

CO: The theme “Collapse: :Rebuild” is a reflection of the entanglement I strive to emulate in my practice and sculptures. There can be beauty in destruction as well as its aftermath, we see that directly in nature by how essential death and decay are to new life. When making, I reference the interconnectedness of all living things. The significance of every organisms’ dependence on one another in a healthy ecosystem and the role that humans play within it drives the purpose of my practice. I work to show the demise of this breakdown when not cared for. Like the ecosystems from which the species derive, every piece of porcelain in my sculptures are connected and interdependent on one another. This interdependence enunciates the vital biodiversity that is required for flora and fauna to thrive in the wild, as well as the interconnected role we play in their survival. In the work everything is conjoined, composing one large interconnected form. In this same way the work is fragile and damage to one part affects the whole. Drawing attention to environmental issues, incorporating education in my work, evoking dialog, promoting curiosity, pursuing mindfulness and taking action to combat crises in nature are all crucial engagements in my artistic practice. They are passages towards living reciprocally with the environment in this present moment and onward.

Spoon-Billed Sandpiper Calidris pygmaea photographed by Carmen Ostermann

Carmen Ostermann (b. Edgewood, Kentucky) is a fine artist who was raised in the United States, Canada, Japan, and the Philippines. In 2015, she received her BFA in ceramics and sculpture at the University of Cincinnati. Afterwards she taught at the School for Creative and Performing Arts, Stivers School for the Arts and A+ Children’s Academy. Ostermann is the recipient of the Wolfstein Travel Fellowship (Frankfurt, Germany), the Margaret L. Gongaware Scholarship, and the Windgate Scholarship. She completed her MFA at the Columbus College of Art & Design in 2022. Her work has been featured in the Roger Tory Peterson Institute of Natural History, the Priscilla R. Tyson Cultural Arts Center, and the Ohio Craft Museum. She teaches ceramics at Capital University and is the Administrative and Project Coordinator at the Columbus Audubon, blending her love of art, education, and conservation.