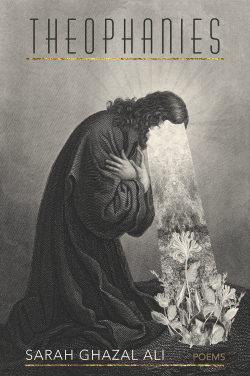

In her already sold-out debut poetry collection, Sarah Ghazal Ali names and renames the places where womanhood, faith, and danger collide. Theophanies, from the word meaning “visible manifestation of God to humankind,” are embodied in these poems through stunning meditations on women from the scriptures. “A name / is a condition meant to last, / to outlast,” Ali explains in her poem “Sarai.” Her collection invokes women like Mary, Hajar, and the poet’s own namesakes alongside contemporary martyrs such as Nabra Hassanen, who was assaulted and murdered in Virginia in 2017. The effect is a book of poems that reads as timeless and unflinching, drawing in readers to witness a feminine lineage of Muslim faith that is, at once, lyric and brutal, gorgeous and convicting.

The opening poem, “My Faith Gets Grime Under Its Fingernails,” sets us up for these complexities right away:

“rather than God’s pristine names

The places I’ve prayed—elevators, Victoria’s Secret

fitting room, the muck-slick meadow after rain—

will testify for or against me,

spilling through my Book of Deeds

in ink of blood or honeyed milk”

The contrasts here are striking as the lines dance effortlessly between the present and the past. This is accomplished particularly well due to the voice of the collection, which reverberates with a prophetic quality, lapsing from the singular “I” to a plural “we,” such as in the poem “Daughter Triptych” where “I dreamed of abortions. Some might have been mine: / oblong pink pills, a curved door handle, wire hanger, unripe papaya” suddenly shifts: “I looked out from the eyes of Maryam. A sharpened stake in our hand…Then I was elsewhere, watching Sarah, aged and exhausted. Her fingers pressed / light against that slightest bulge.” In the span of a few lines, the triptych takes on the personas of three women, each with their own distinct experience of pregnancy and embodiment, united over time and space through the simultaneity of the poem. Similarly, the poem “Magdalene” opens, “God made laughter for the third incredulous woman. / We cover our mouths, ashamed to echo what’s hers. // We bleed as punishment for the curious first.” The plural pronoun takes on many shapes, encompassing the three women, then all women.

There is a distance to the voice of Theophanies that struck me immediately—how the speaker of the poems holds her own stories at an unflinching arm’s length while pulling scriptural figures like Maryam and Sarah close enough to touch. The balance brings the present into the lineage of faith and history in a way that feels both distant and intimate, vulnerable and profoundly wise. “Faith [is] a legacy / of echoes,” Ali expounds in the poem “Temporal.”

Perhaps this echoing is what makes the ghazal such a perfect prominent form in this collection, right next to the persona poem. The ghazal is another namesake of the poet, which she takes advantage of, playing with the doubling in “Ghazal Ghazal”: “My people must include my father, his voice lilting from baritone to bellow. / Did my god not make his mouth, aural imprint of every remembered ghazal?” Ali cements herself as a master of couplets, and this couplet form especially, building the repeated words of the form into a haunting refrain:

“Blasphemous how one begets many. Father, father, daughter.

& your mother? Miraculous origin- the one safe country.

When they ask, Ghazal, if you anger, recite again: men

Flee the wind for the anthem of a new country.”

—“Partition Ghazal”

The ghazals harmonize with the relational complexities that braid through the collection as the speaker looks to the more immediate lineage of her family—from childhood memories of playing with a plastic brain model with her father in “Temporal” to the more solemn account in “Motherhood 1999” where the speaker tells us, “That year my mother made herself tall / with routine, nutrifying / my body… First triumph of her spine, the only daughter— / followed by son and son.” Ali’s familial accounts are a dynamic testament to her diasporic Pakistani heritage, exploring what is received and what is passed onward with tenderness, defiance, and longing while pushing against the constraints of patriarchal tradition.

“Recite to me a single memory not manufactured.

Even a mother is myth, fabling

to survive a marriage miscarriage man.”

— “Daughter”

In this way, Theophanies is a beautiful and deeply matrilineal text, a landscape splashed with the red of poppies, birth, and blood. Readers, too, are incorporated into this inheritance through the scattered, repeated commands like “recite” and experimental forms like the family tree shape of “Matrilineage [Recovered]” where we weave our way through the maze of generations to decipher the poem.

Overall, this is a book that is revelatory, solemn, and stunning, where the exquisite music of the lines and exacting, enjambed sentences peel back to reveal new layers, like “the untorn snakeskin I found / while digging for wetness in the sand” in “Epistle: Hajar.” Theophanies is a timeless poetry collection: ferocious, lyric, and resonant, and an instant classic on my bookshelf. Like its predecessors, the words of Leila Chatti, Kaveh Akbar, and Mary Szybist, Ali’s poetry shines with a gritty, ethereal faith—the kind that “gets grime under its fingernails,” the kind that brings readers to their knees.