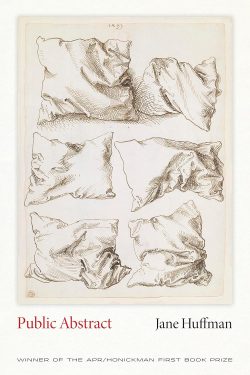

The entry points of Jane Huffman’s beautifully precise Public Abstract are two epigraphs, from Jean Valentine, “but to say I know, is there any touch in it?” and sculptor and artist Louise Bourgeois: “Pain is the ransom of formalism.” These epigraphs introduce us to some of the central concerns of this collection: pain and illness, form, both knowing and its impossibility. We begin with that quintessential impossibility to fully understand and articulate what a book is “about,” as Huffman’s first section, titled “A BOUT,” embraces and turns into structure. A poem in this section begins “I had a bout / of something / Undefined,” and many of the poems in the collection are pleasingly resistant to aboutness. The collection as a whole becomes a bout, a reckoning, with the desire to fit experience into formal shapes and the pain of that impossibility.

A bout can also refer to a period of time, and in their rhythms and meters, these poems attend to time self-consciously through their metrical patterns—we hear and feel time passing in and through them. “[I had a bout]” goes on to describe the “something / Undefined” as “a clocking from within.” While explicitly describing vertigo, the diction here also gestures to keeping time, and with their iambs, trochees and rhymes, this poem and many others move at the pace of a ticking clock. Charles Simic famously wrote that “the secret ambition of all lyric poetry is to stop time,” but Huffman’s formal pieces seem to create time, propel us through it, and hum with a daunting reminder that time will never stop. In thinking through these pieces, I recalled the final lines of Omatara James’ poem “A Flair For Language,” where her speaker describes rhyme as “the coincidence of language and time.” Language, in time, for Huffman, is constructed by forced coincidences: coincidence shaped into forms.

In “Surety,” the speaker repeats an onslaught of cumulative similes:

“I’m sure as wetness

follows steam.

I’m sure as cold

that follows

wetness

follows steam…

…

I’m in the midst

of sureness,

sure as bricks.

I’m sure as cold

that follows

wetness follows

mist…”

As when an interlocuter repeats their argument so many times they become unconvincing, the accumulation of sureness metaphors in this poem creates an ironic weather of uncertainty. The poem admits as much at its close:

“I’m in the heat

of surety. The bleat

and seethe of surety.

The mist

that follows certainty.”

The speaker perhaps tries to be sure and fails to convince themself. Even so, the rhymes that punctuate this metrical piece create a musical confidence that complicates the anxiety. And throughout all the book, as the poems circle their questions and enact their recursive procedures, Huffman’s precise meters keep the language moving at an assuring clip, even as we encounter the abstract and the formally complex. Sound is in lockstep with the crystal logics on these pages, the tightness of their rhythms, from the titular and first poem, “Public Abstract” –“I swept / and am sweeping, / have slept / and am sleeping.”

The four sections that follow A BOUT also seek understanding and attempt to cope with the impossibility of fully knowing in their own ways. In the section REVISIONS, the poems resee, rewrite, and interrupt received forms such as the sonnet, sestina, and ode, as a form of continued desire for understanding and articulation of the world. The poem “Revision” uses shifting repetitions and brackets to add layers of meaning to a meditation on body and mind, form and formlessness – “Like a crowd, a body moves without a mind” later becomes “[The] body, like the mind, moves in crowds,” which later becomes “The body moves with [crowded lines].”

These revisions are numbered, giving a sense of their progressive making through time. All of Huffman’s poems honor the word poem’s etymology in their careful construction– they are made things. What the movements yield are original lines and beautiful ways of thinking about forms in the world: “[The wave, a solitary interaction of] the wind. [The kiln is thinking itself warm.]” later becomes “[The wave with the mind of a] kiln, thinking itself warm.”

The section LATER FRAGMENTS frames sparse poems as additions and attempts to further clarify an argument, though the argument itself shifts and changes. Later is an intriguing time marker in the story of the speaker, another reference to time and its passing, even in a book that resists a classic narrative. In one of these fragments, the speaker invokes their “causal impulse” as indulgent but unputdownable:

“If I am

Indulgent tell

Me how

To put this

Causal

Impulse down

Back in its

Spring-

Loaded box”

In a series of numbered prose blocks, the penultimate section, ON INVENTION, holds some of the rare personal specificities of the speaker, interspersed with meditations on Cicero’s De Inventione. The title and the analysis of Cicero’s history / fable / argument, negotiate with the invention of the self as another mode of knowing. In the final poem of the series, Huffman writes, “I invent a future version of myself who changes her mind…in the fable of my life, I was born childless. History congeals into fable, and fable argument. One side covets the past, the other the future.” Time returns here to haunt, backed by the fraught abstract and specific experiences of illness, familial addiction, anxiety, and intellectual questions these poems negotiate.

The final section turns to haibun, the traditionally Japanese form originated by Matsuo Bashō, with prose blocks followed by summative or emphatic haikus. Huffman’s haibun in this section all have declarative titles (“On moving,” “On beauty,” “On theatre,” “On breath”) that evoke the sense of aboutness other poems seem to reject, though they stay mysterious, complex, and rich in their language. In “On knowing,” the speaker says, “What I didn’t know grew over what I knew,” in a declaration of unsurety, but also of the passing of time that creates the sense of self.

Throughout the whole collection, influences and intertextualities abound. This is a book that is immediately pleasing to the ear, but also one who benefits from the close reader willing to attend to the author’s references and influences. The poems honor in form and reference luminaries such as Emily Dickinson, Kay Ryan, Jericho Brown, Rilke, John Donne, Dionne Brand, and many others unnamed. Huffman is a poet and a thinker who understands that poetry is a collaborative act.

As Dana Levin writes in the introduction to this APR/Honickman First Book Prize winner, for Huffman, “singing reveals knowing, rather than knowing sparking song.” Singing reveals something else, too—

a touch of the private feeling that is present behind all of Huffman’s public forms and rhetorical satisfactions. While specific confessions appear rarely (though importantly) in the open language in the book, rhymes drive the engines of emotional resonance, as the final haibun confesses with its moving haiku: an admission that is more emotional than rhetorical, though of course it is both: “Rhyme is so public. / Weeping openly / in a crowded latitude.”