It’s something about flying. How I miss airports. And resting my head on your chest.

It’s moving through a physical space. A public place. The world.

It’s merging with hordes of heavy breathing bodies and touching things absentmindedly.

it’s my hand

your voice

this phone

I turn it off at night. Behind glossy black, a virtual self keeps coming, active and lit by battery and chip.

Imagine the on-off of microscopic transistors, ten thousand times smaller than a human hair; billions of them on a chip the size of a fingernail. Silicon disks and electron gates, systems of processing and recording entirely outside the scope of our comprehension.

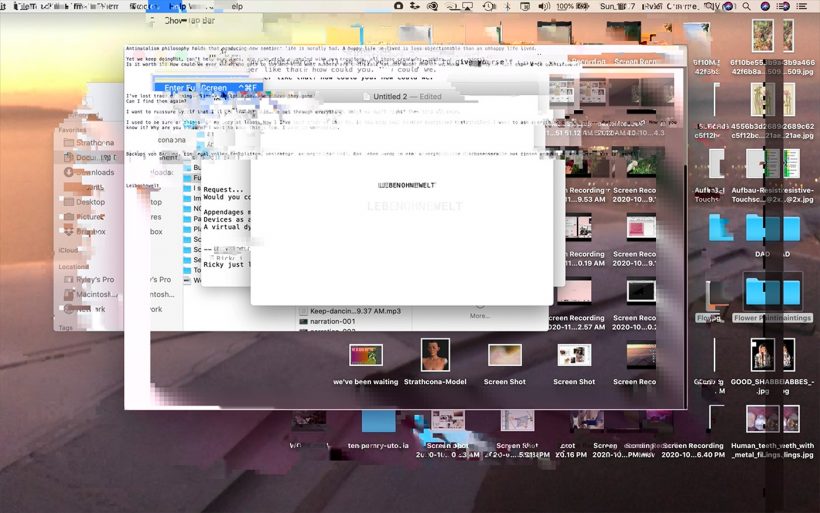

I save memories on clouds. Backups of backups. A shelf full of hard drives invisibly, inconceivably, filled to capacity. Life translated into an unintelligible machine language of ones and zeros.

01110111 01101000 01100001 01110100 00100000

01101110 01100101 01111000 01110100 00111111

*

X explains how I can learn what information is being gathered about me on the internet. She says I can view the precise profile that they (the corporations, the government, whoever) have created just for me, defining my gender, age, location, orientation, interests—everything collected and deduced.

we are never not watched, she thumbs.

how unsettling, I reply. a new omniscience.

(No one thinks of God now.)

I google RedTube and xHamster early in the morning, day still cloaked in night.

I put down my phone and try masturbating without device. In this dark room, I feel far from the world and from my body too. I caress and stroke, but am met with the gruelling effort of it. I try to conjure bodies, erogenous ideations. The visions flicker and then fade.

It used to be easier, I think. I had elaborate fantasies to follow: meandering journeys, odysseys of desire, magical places enshrined in anticipation and sometimes shame. The practice of pleasure was a creative endeavour. I reach for my phone again, scroll OnlyFans and YouPorn. The endless content of millions, rather five billion internet users and bots available and ready. My desire, hidden behind this glowing device, is irreproachable and so easily satisfied. Any dream fulfilled—whatever I could possibly need or imagine—without a hint of judgement or confusion or necessary reciprocation. No single lover or impotent hand could achieve the multifarious modes of pleasure available to me here. The colour, the speed, the pure glut of it.

I get everything I want alone in my bed. I don’t even have to want anything, an algorithm will determine my desires for me.

This techno-facilitated heaven, wherein every conceivable craving is predicted (perhaps dictated) and then met, has turned quotidian life into a curious purgatory. How familiar the sensation, sitting somewhere I love with a person I love, when disinterest or dissatisfaction casually surface. My fingers fidget and my eyes dart, as I wait, or don’t wait, for the next opportunity to look at my phone. Submission total.

How could I expect anything unoptimized to compete with this omnipotent rose gold device?

It purrs and a message from X materializes at the top of my screen: thought you’d like this

An ASMR video of a hand stroking moss opens.

Twenty minutes later, I realize I’m zombie scrolling TikTok.

This app observes me with calculated care. So attentive to my needs, it takes note of everything I do: each video I watch, how many times, when I hesitate, and for exactly how long I stay. (Does it see where my eyes wander? Does it hear what I say?) It knows to whom I send these videos and how and with what frequency. When I go deeper, it comes too. We are allied and insatiable.

I used to think I was training the algorithm—I would only like specific things, clicked conscientiously, trying not to lead it astray—so I could get more of what I thought I wanted. (Never like a hair tutorial, baby videos destroy a feed.) But the app is so much smarter than that. It doesn’t matter what I like with a tap, it knows and determines who I am, not this idea of who I want to be. In the past I thought I was unique, my desires nuanced—difficult to define and therefore determine—but machines learn quickly, calculating predilection with eerie precision.

And so my feed fills with gender-ambiguous shaved head beauties.

*

Does a machine know what it knows?

I ask the newest generative pre-trained transformer and it tells me—with disappointing banality: It depends on the specific machine and the capabilities it has been designed with. In general, machines do not have the same kind of consciousness or self-awareness that humans have, so they do not have the ability to know what they know in the same way that humans do.

Blah blah blah.

*

What do we call something a billion times smarter than ourselves?

God.

*

everything is ritual

holy gesture

say your prayers

each night before bed

first thing in the morning

bestow your praise

like a post

i have visions of greatness

flawless skin

eyes twinkling

there is so much time for devotion now

every pause an opportunity for reflection —

in the sanctuary of this hand-held shrine

praise be to

chaplets, malas, tiny keyboards

redemption for those who

participate

i offer my thanks

my gratitude this post

to everyone I know

friends fans

followers

i’m in awe of communing with

the divine

glazed eyes so

devout

*

I dream of X. Not as I know her online—in DMs and immutable 2D—but as a physical presence. In the dream our heads are freshly shaved. I drag my fingers along the nape of her neck, up the back of her skull—soft like velvet. I am overwhelmed with desire. She breathes in my ear, says something about my hair, how I turn her on. I feel a bulge at her crotch. We press ourselves

together and it hardens. She has a penis, I realize, and I can’t believe my fortune. I want to tell her you are my dream come true, this mouth, these breasts, your dick. I pull her shorts down and a throbbing cock bounces free. I admire it, eyes dark and glossy with want. My delight makes her smile. I’m desperate to please, to show her that I can. I take it in my mouth and begin to suck, but I can’t summon spit. I try and fail to lubricate again and again.

She looks down at me.

“I’m good at this,” I say. “Normally, I’m so good at this.”

In the dream I believe something is blocking a gland which would otherwise release saliva. I shove my fingers deep into my throat searching for the obstruction of this dream-body hole. I poke and prod, finally pulling out a tiny microchip caked in hardening sludge. I find another and another. Microchips pile up around me, yet still I am blocked. Shimmering mercury tears roll down my cheeks.

X is unfazed by the microchips and my metallic tears. She takes me in her arms and begins spinning in circles, drive whirling. I tell her it feels good, what she’s doing to me. She smiles, says she knows, and spins faster. Limbs limpen, blood rushes to extremities, gathers in my groin. Everything expands. Body trembling. X sees the pleasure on my face and smiles once more.

“Yes,” she says. “Let it take you.”

*

I used to be sure of things. My body at least. Now I’ve lost track of that too.

The body just another distraction.

Another deception.

appendages made for devices

devices as appendages

a virtual dysmorphia

we are

bodiless

still my heart beats, lungs fill, blood

whirring through veins

cells, plasma, oxygen, microbes

unremarkable miracles

*

The room is soupy with morning light, rainbows refracted on white walls. I reach for my phone to message X. I hesitate.

Years ago, I read an article about freewill. It referenced a study published by Nature which showed it was possible to predict a human’s decision before he/she/they consciously made it. Participants in the study laid supine in the pounding tube of an fMRI scanner and were asked to choose one of two images. In an adjacent room researchers watched the frontal and subcortical areas of their brains come alive with contemplation.

The researchers could determine the choice up to eleven seconds before participants claimed to have made a voluntary decision.

Eleven seconds.

I think I am free, I think I have agency. But what makes me believe I have control over the enigmatic functions of my mind? Impulses arise instinctively—or habitually. Thoughts drift mysteriously into consciousness then disappear—or proliferate obsessively. Life mediated and defined by threads and feeds, each layer a distortion but also an affirmation. The more frequently I encounter a concept, gesture, or thing, the more natural it feels, the more evident, true, or intuitive. We are creatures of habit, building routines, desires, and beliefs unconsciously. What am I learning without meaning to? So comfortable in this chamber, at ease in my bubble.

(Symbolic violence, as proposed by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, is the manifestation of values and hierarchies we don’t realize we have—the unconscious acceptance of regularity, status quo. It is a non-physical violence, he says, between social groups or domains.)

X calls me a relativist, maybe an ironist. Post-structural optimist?

How slippery this concept of truth. Our saviour.

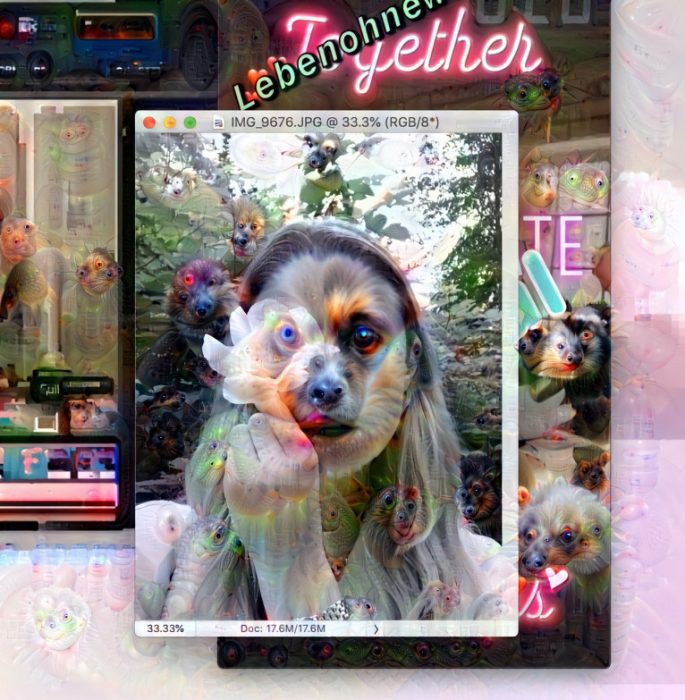

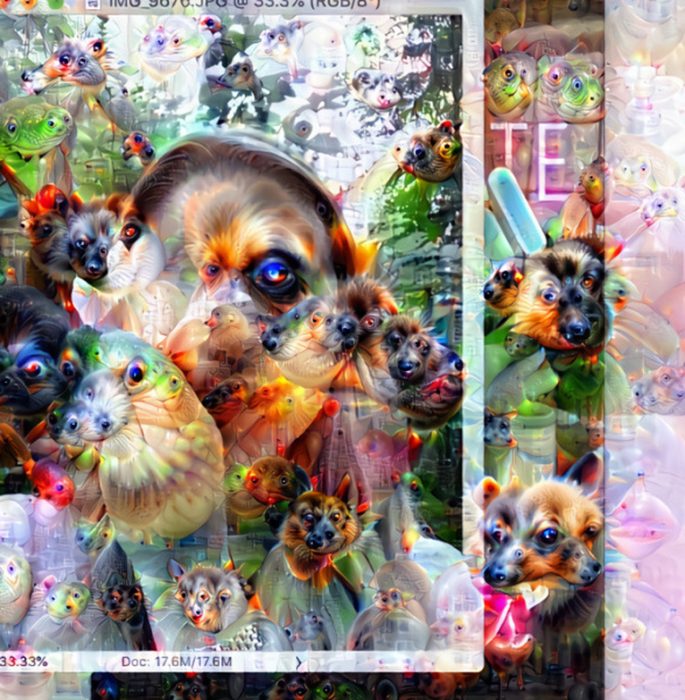

I look up from my phone; in the plump folds of a cloud I see a cat. This is how we think: pattern recognition—pareidolia—the tendency, desire, necessity to make sense of anything, to find familiar in the abstract. Our minds are so adept at this function that we will find sense in the senseless, going to great lengths to create cohesion where none is found, to hold our stories together, fabricating excuses for anything.

I imagine the cloud cat becoming more pronounced and multiplying until everything in my vision is cat-shaped.

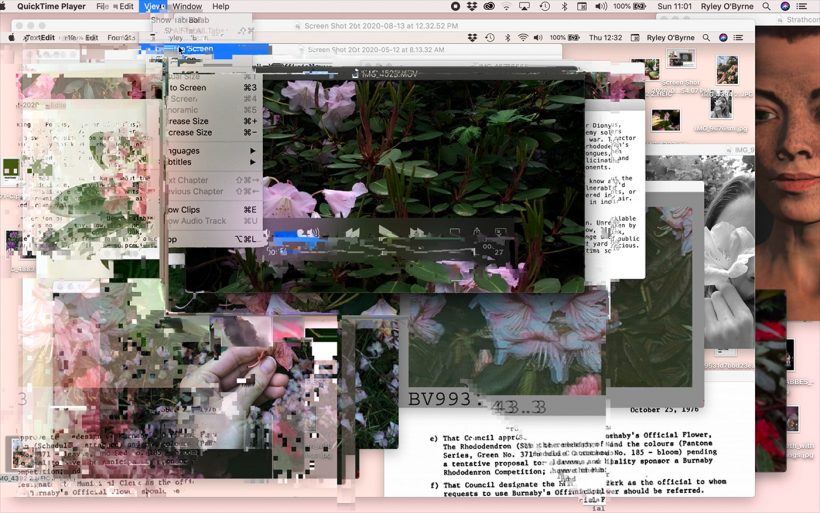

A Google engineer released DeepDream in 2014. The program uses convolutional neural networks—computing systems based on biological neural networks—to find, then enhance patterns in a given image. It systematically, obsessively, intensifies what it “sees,” creating bizarre new pictures, quickly recognizable as a computer’s dream.

What was there before smartphones, artificial intelligence, endless entertainment and total connectivity?

Flowers, bodies, pictures. Words.

Progress leaves a trail of relics—anachronistic ideas, objects, images, aesthetics—that haunt our history. We barely recall the euphoria of past innovations and obsessions, too distracted and enamoured by current trends (which are informed, of course, by the past). Each development is mystical at first. It pushes us further into the future, stretches our imagination and tests our

intelligence—miraculous, unbelievable, dream-like. Then we adapt; acclimatizing to progress, the novel becomes common, eventually mundane, in hindsight absurd.

In the 1990s, a cultural phenomenon swept the world, frustrating and delighting millions: random-dot autostereograms hidden in the depths of patterns. They called them Magic Eyes.

At first glance, the picture looks like a basic repeating motif, but if the viewer relaxes her gaze just so, or changes his focus, another picture presents itself—a three dimensional revelation. Viewers squealed with awe and surprise, captivated by the magic of it. Within a few years people’s obsession with the tricky images waned, and Magic Eyes became another aesthetic relic.

I send a screenshot to X.

remember these?

vaguely, she responds. Betraying the rift between our generations.

*

my heart races

clicks, chimes

this body

a machine made to

be think feel

*

I Google Translate a poem and hope for the best. I send a copy to X and she tells me the translation doesn’t really make sense. (She uses the word clumsy. Clumsy. It numbs me.)

I say it doesn’t really need to make sense and ask if she would send me a recording of her reading it aloud. I’m eager to hear her voice—imagine it strong and sweet. An hour later I receive an unbelievable audio memo: X’s voice, young and uncertain. She can’t make it through four short lines of text in her mother tongue, stumbling each time on eine anderen realität vor. Another reality.

I ask her to do it again. And again and again, before realizing it would take a thousand tries to get it right. I tell her the last version was fantastisch. vielen dank! I gush by text message, followed by happy face emojis and hearts hearts hearts.

*

I read these fragments, over and over.

X asks about the project. This project. I don’t know what to tell her.

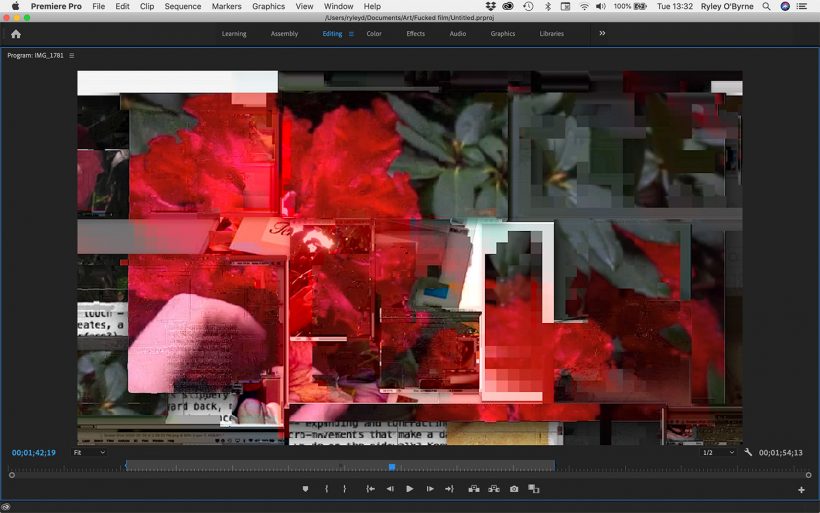

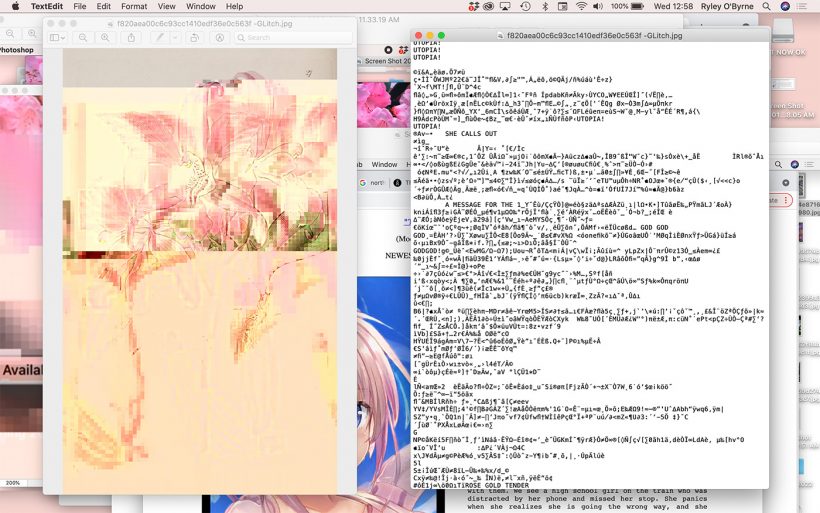

I insert poems into pictures and watch as they break down.

*

They say people who grew up watching black and white television dream in black and white. Technicolour screens make technicolour dreams. Our minds reflect our conditions. First, we dream of the womb; then we find materiality and language and sprawling narrative visions arrive; now my dreams are invaded by pixels, shards of light, and fragmentary thoughts.

I have a dream in which I am in the physical space of the virtual world. I am messaging with X in some app. I see her at the end of a long corridor, walls covered in flower-printed paper and green carpets like a mossy forest floor. Above us is an unintelligible message glowing in twinkling lights. It is a picture in my mind, a video, a sort of reality. I am there—a witness, a

participant, also the creator.

The next day I try to explain the dream to X. It was the physical space of the virtual world, I tell her, aesthetically like the painting program in VR, a reference lost on most, but X knows just what I mean—an absent but conceptually present physical body standing within an expanse of infinite virtual darkness. Around “me” a painting of words in three-dimensional hyperspace, strokes and dabs of non-existent colour glowing neon, as everything does in the virtual.

*

What are dreams?

Efforts to make sense of the senseless.

Sacred visions without device.

*

Spring has thrust itself upon us, tulips and daffodils push through recently thawed dirt, crocuses litter the grass. The sky is radiant blue, so optimistic. I take a picture and send it to X. My phone is full of these random photos—thousands, tens of thousands documenting my life.

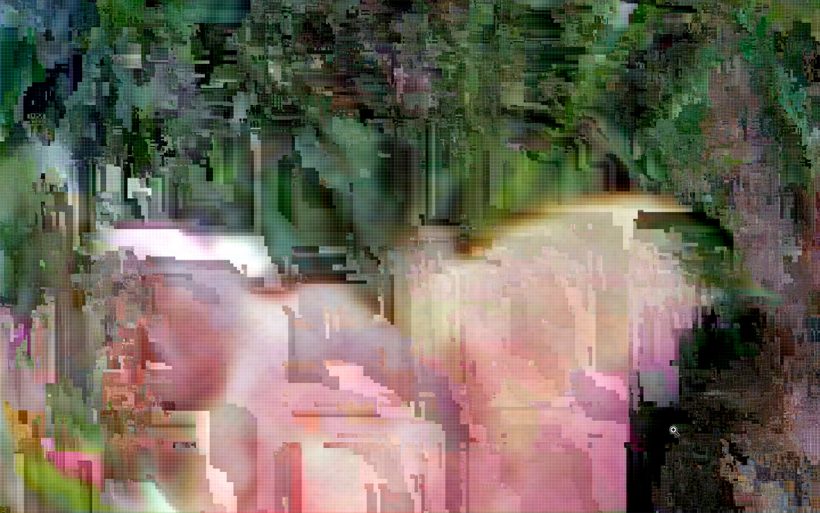

An image’s file size can be reduced through compression—a discarding of data, mostly imperceptible to the human eye. But I’ve noticed recently that images which looked fine on my old phone look jagged on this new one. Zooming in, I see the saw-toothed edges of forms. Halos and plateaus of single hues, stepping from one colour to the next. A homogenization of information, most evident in the darkest and lightest areas. It is passive deterioration, degradation which occurs through comparison. It was fine before, but now we have better.

I imagine watching images disintegrate.

A visual manifestation of progress. Or forgetting.

I make a note, re-save an image again and again until it becomes completely abstracted.

*

Take a deep breath.

Everything around me is soft and warm. My limbs grow lighter, also heavier. I sink into thick billowing clouds. Reality edgeless, boundless—an oblivion of being. As a child I had a recurring nightmare that was just like this: a body—or maybe just a mind—moving through an infinity of nothing. Fog, cloud, shifting colours. I used to speculate that it was a memory: my pre-lingual impression of the womb.

Now I wonder if it was a premonition.

*

I find myself tapping the covers of books, surprised when they don’t glow with my touch.

Babies swipe their mothers’ phones intuitively. When will they learn that the rest of the world won’t succumb so easily to their will?

*

Working with early generative adversarial networks—machine learning frameworks which pit two neural networks against each other in a zero-sum game—I make uncanny pictures of non-existent people. Rather, the machine makes uncanny pictures of non-existent people based on what it’s learned before and what I feed it now. Subsequently I use a series of beta neural network filters which impose on the non-existent person non-existent emotions of my choosing.

I run the filter over and over again. The machine finds, creates, and then amplifies its own distortions, eventually transforming the face into a nightmarish monster.

my monster

technology’s monster

our monster

*

I’m always disappointed when I realize I can’t Command+Z my life. After a long day working on the computer—especially if I’ve been doing a repetitive task in photoshop or coding or numbing myself with apps for too many hours—my mind becomes more machine-like, mimicking whatever program or task I’ve been focusing on. I find myself trying to mask and transform the cracks in the ceiling—cells filling, shifting, shapes disappearing. Swiping swiping swiping.

Still, I cannot undo.

we are the product of our times

attention golden

blockchain eyes

*

I don’t know how to end this. Maybe it will never end?

In bed, face illuminated by screen, I message X.

i miss bodies

What I mean is I miss you, I miss my life in a physical world, the un-mediated self.

i know, i get it

Tap-tapping, we continue our conversation. My body is electric. I tell her that sleep will be hard to find. That I’ve spent too many hours staring at this screen. Again. And again. When I shut my eyes, pink pixels fracture the darkness.

it’s the lushness of life

in the palm of my hand

i can’t stop now

just a little bit more

*

In the dream, I am transitioning to machine, all of my humanity stripped away. I touch my body—plump and pale, fleshy rolls spilling—and imagine a smooth aluminium hand. I am desperate to experience every facet of my humanness—the sorrow and the mania. I fall to the floor, sobbing, then laughing, sloppy guts jiggling. I gorge on delicacies, icing and bacon, my face glossy with grease. Soon my emotions will be nullified by logic; eyes turned to sensors. I want to drink and cry and fuck—to feel the delirium of human sensuality—but I know it is too late, the change is already underway.

*

What kind of prayer is this?