Where sticky layers and associative leaps meet torn textures and graphic contrast, Erica Trabold’s collages evoke feelings of nostalgia while troubling the very act of memory. “Circling the Square” embraces the materiality of the past in order to interrogate our ever-changing present. Art Editors Heather McCabe and Misha Ponnuraju interviewed Trabold about the collage form, its relationship to writing, and what rewards there might be in looking closely:

Misha Ponnuraju: I love that you describe yourself as an essayist who works in collage as an extension of your creative practice. How do the two artistic ventures intersect? Do your collages inform your essays or vice versa?

Erica Trabold: I see everything I make—whether it’s an essay, a collage, or something in-between—as output of the same creative energy. Writing just happens to be the artform that was most consistently nourished by the teachers and communities who supported me as a young person, and so for the last decade, I have been building on my identity as an essayist. Writing will always be my first love, but I found it extremely difficult to do after I had a child. Every parent-writer I know told me this would be the case, but it was still shocking when it happened to me. I no longer had the headspace, the hours, the undistracted moments of reflection necessary to put my experience to words. My focus, understandably, shifted elsewhere. The scariest part was wondering if it was going to stay that way forever, but I gave myself permission not to write for as long as it felt necessary. After about a year and a half, I realized that my creative energy had been churning beneath the surface the entire time, and suddenly I had access to it again. I started making collages and writing found poems, often combining the two, almost every night after I put my daughter to bed. I couldn’t stop. I kept the stakes low. It was all play, allowing myself to be intuitive and associative with colors, words, images, and materials, and it was nurturing, too. I hadn’t collaged with any regularity since I was a teenager, so it felt like running into an old friend and picking up right where we left off. I’ve become newly interested in creating visual art and experimenting with the ways images and language can fuse physically on the page.

Heather McCabe: I’m also curious about the relationship between your collages and essays. We talk about the lyric essay having an associative or “sidewinding logic,” and I wonder if you feel any relationship between the collage form and the lyric essay?

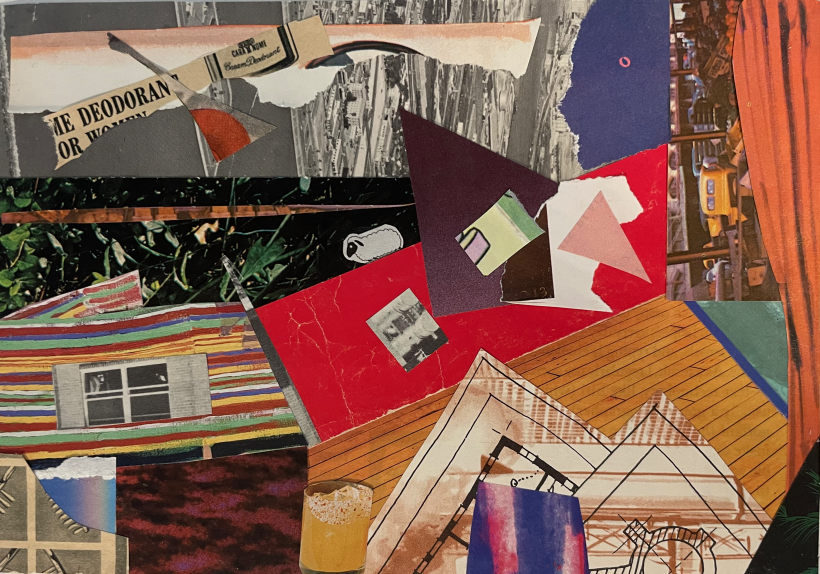

ET: For a while I was keeping this collage obsession to myself. There was no small amount of imposter syndrome, considering I am a self-taught visual artist. When I confessed to one of my close friends who is also a writer, she wasn’t surprised. As she put it, “collaging is exactly how you write.” I don’t think I needed her to point out the obvious—that both collage and lyric essay rely heavily on repetition, juxtaposition, images, and the purposeful gaps between them—but I did need to hear that kind of validation from someone I trust. Every writer has their own set of strengths, and mine lie somewhere at the intersection of association, arrangement, nonlinear storytelling, and poetic or, as you say, “sidewinding” logic. While I’ve trained as an essayist, my natural strengths translate beautifully to collage as a visual medium.

MP: What is your collection process like for your collage? What materials are you drawn to? Has that changed over time?

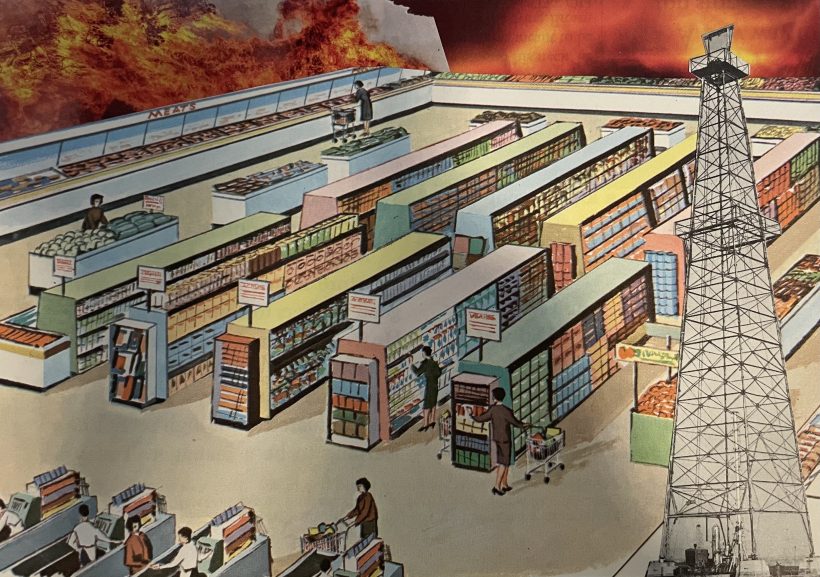

ET: The best thing about collage is that it’s accessible to everyone. You just need scissors, glue, and paper. Maybe not even scissors. In the last few years, I have been more intentional about my collecting, but for the longest time I just made art from whatever I had, which was mostly circumstantial. I grew up in a rural community without access to many second-hand shops. As a teenager, I collaged from personal photographs, my mom’s old magazines, whatever the library was throwing away, and my back issues of Teen Vogue. (I used a lot of Teen Vogue.) My collage materials are no longer as contemporary, although I’m not adverse to it and almost always incorporate something torn or cut from a magazine page. The writer in me loves having an excuse to buy old books. I look for the strange and the odd, the maybe-not-quite-so aesthetically pleasing. Bright colors are a must, but the subjects vary widely. I recently came home with a stack of books from a $1 sale about such things as: maskmaking, floral arrangements, film photography, and folk art motifs. Anytime I find old sheet music, I buy it—those are my absolute favorite material to work with. The ones I’m drawn to are hand-illustrated with bold colors and unusual patterns, and the paper is worn in ways you can’t imitate. I’ve found nothing that comes close to matching their charm. But I don’t often go out and source material with a specific project in mind. I work with what I have on hand, and that restriction usually leads to unexpected creative insight.

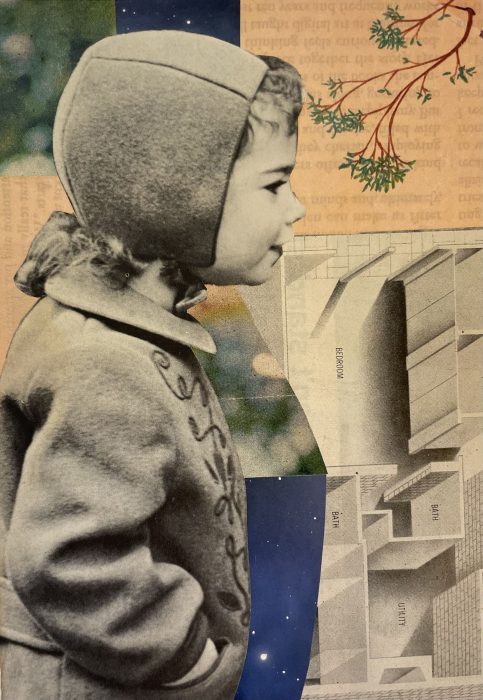

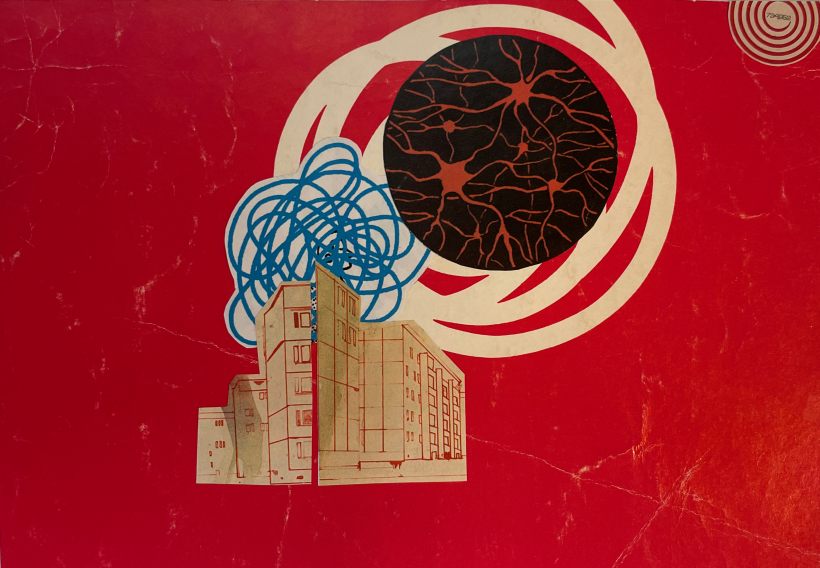

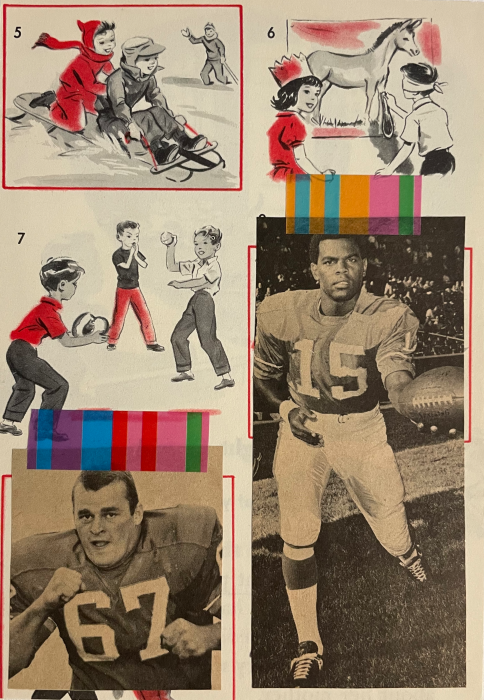

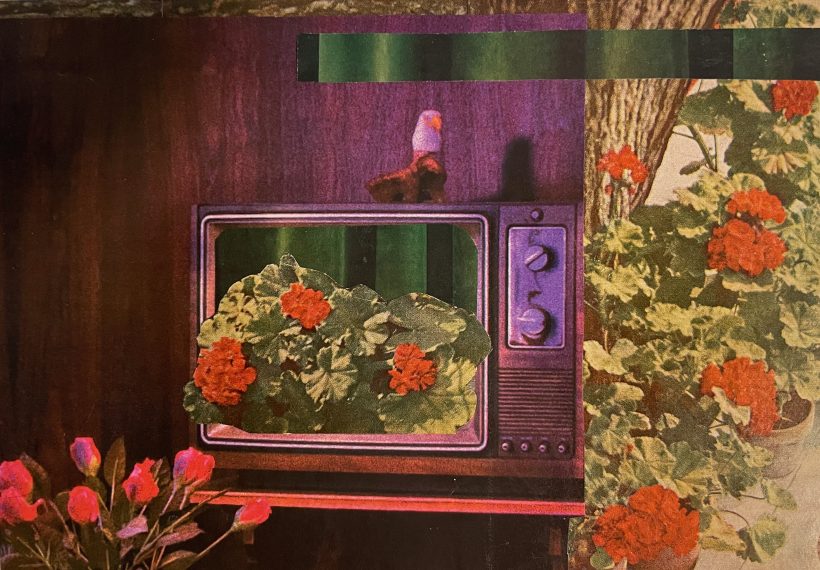

HM: I’m drawn to the material textures in your collages, the creases of paper, and the cut or torn edges. How are you thinking about or troubling ideas of perfection or preservation in this work? I’m thinking particularly of “Play” or “Curtain” as examples that challenge boundaries and borders.

ET: I don’t find perfection interesting or attainable. If you’re going to use old, fragile paper and vintage ephemera, you have to let go of any expectation that it won’t tear or fall apart. If an image is torn, creased, or discolored, I like to use that to the work’s advantage. The viewer should be able to engage with both the physicality and age of the materials, to consider the life they lived before they were manipulated and glued to the page. The imperfections of the paper, quite literally, add texture to a collage. As an essayist, I think about this a lot metaphorically. No story is quite believable if everything goes according to plan, without friction or conflict, and no character is quite relatable without a set of flaws. Everyone and everything has rough edges. Even in creative nonfiction, when the story and the circumstances are true, we have to write with this in mind.

HM: What’s the role of color in your collages? I’m noticing the prevalence of red as well as black and white images, the combination of which evokes technicolor for me. Is that something you’re conscious of in the act of creation?

ET: With this series, I think I was aiming for something technicolor-adjacent. Most of the paper materials I was working with came from about that era, printed in the 1950s and 60s. This is certainly an effect of my collecting habits. Whether I’m shopping for collage materials or for clothes, I gravitate toward unusual patterns and warm tones rather than cool. Blue is my least favorite color (don’t ask me why), and I probably incorporate shades of red most frequently. Red is bold and striking, especially against black and white—I just find the contrast stunning. It’s my hope that using bright colors can first catch the eye, then reward closer looking.

MP: Is there anything you’re excited to explore, in either essay or collaging, in the near future? What is exciting you artistically?

ET: I’ve become fascinated by altered books. Right now, I am working on my first, a project that fuses collage and found poetry to alter the pages in a decommissioned library copy of Willa Cather’s The Song of the Lark. The original text is about pursuing an artistic life—the novel has buoyed me in times of uncertainty, and it’s my favorite book by Cather, a fellow Nebraskan writer. I’m calling my alteration “The Lark” because for me it has become “something done for fun, especially something mischievous or daring.” I mentioned earlier that this project began as a gateway back to my creativity after becoming a mother. As it’s currently taking shape, “The Lark” is full of colorful chaos. Between its covers, no two pages are the same. These juxtapositions—and contradictions—speak to the experience of early motherhood. Its sameness and unpredictability. Its confines and freedom. Its brevity and breadth. The time in a woman’s life when the features on her face may be dull, but the colors in her mind are bright, and exploding. I hope this ongoing project bears witness to the experience of transformation—it’s darkness and messiness, alongside the euphoria of becoming new. It’s an acknowledgement that I am not the same, and with me, my art has changed.

Erica Trabold is an artist, essayist, and author of Five Plots (2018), winner of the inaugural Deborah Tall Lyric Essay Book Prize, and the chapbook Dots (2021). In 2023, she co-edited the anthology The Lyric Essay as Resistance: Truth from the Margins (Wayne State University Press) with Zoë Bossiere. Trabold’s essays, fragments, and collages have appeared in Brevity, The Rumpus, Passages North, The Collagist, New South, Seneca Review, and elsewhere. Erica writes and teaches in central Virginia, where she is an Assistant Professor of English and Creative Writing at Sweet Briar College.