Each blurb on the back cover of George David Clark’s Reveille—winner of the 2015 Miller Williams Poetry Prize—identifies the surreal, dreamlike element of these poems, an element that is of our world, but not quite. Reveille, French for “to wake up,” is just that—a call to attention. It is also a view of this and other worlds that reaches past literal experience and into the realm of the imagined. But this is not a surreal book. We aren’t being asked to leave realism behind. Rather, the poet asks that we reconsider boundaries of our existence, of our realities, of our imaginations, and of our conceptions of religion and reverence. To do any of that, we must, first, wake up.

Special Features

Lo Kwa Mei-en’s inaugural poetry collection Yearling asks no easy questions and provides no single answer—rather, it gives us duality warped over and over. She moves effortlessly between the violently sexual and sexually violent, the poems overlapping one another, not unlike an embroidered backstitch. Images and language are reused and re-imagined; we never read them the same way twice. The sea is dark and ruthless in one moment and the tides are agents of change, “made in the image of a shut door,” in the next. Embedded in this interweaving is the glimpse of a family narrative, of migration, and of the cyclical nature of a woman’s place in that journey. The speaker never shies away from self-damnation (“I am half-spent and hell-bright as / the bad ones are, mother, a flicker deeper than the sea”) and we feel the crushing weight of feminine expectation in “Rara Avis Decoy”: “My name is I know not what I am / as a country of mothers and fathers comes down.” Mei-en gives us a grim and foreboding portrait of the future in “The Extinction Diaries: Psalm” when “the white coin of vertebrae // in a bowl of hips tells the future. May the meek inherit / something dangerous. May I.”…

Marcus Jackson was born and raised in Toledo, Ohio. After earning his BA at the University of Toledo, he continued his poetry studies at NYU’s graduate creative writing program and as a Cave Canem fellow. His poems have appeared in The New Yorker, Harvard Review, and The Cincinnati Review, among many other publications.

Marcus Jackson’s chapbook, Rundown, was published by Aureole Press in 2009. His debut full-length collection of poems, Neighborhood Register, was released by CavanKerry Press in 2011. His next collection is forthcoming in 2016. Marcus lives with his wife and son in Columbus, Ohio. He will serve as the guest editor for the 2015 The Journal/OSU Press Wheeler Poetry Prize.

Recently, Jackson spoke with poetry editor Willie VerSteeg about his influences and writing process.

Willie VerSteeg: What recent books of poetry have been holding your attention?

Marcus Jackson: I’ll be loose with the word “recent,” since I’m always going back to things I’ve already read and loved, in addition to latching onto great, brand new books the first time around. Staring with the quite new collections, I love Ross Gay’s Catalogue of Unabashed Gratitude, Malachi Black’s Storm Toward Morning, and Claudia Rankine’s Citizen. In these books live abundances of emotional flux, lyric force, and intellectual precision.

As for a few books I’ve read the bindings off of and that have been calling me back lately, Tracy K. Smith’s Life on Mars, Ted Kooser’s Delights and Shadows, and Philip Levine’s One for the Rose. Life on Mars is a masterful collection in many ways, especially in how it incorporates such a variance of scale among its subjects and tones. Kooser is a sorcerer when it comes to making everyday objects and scenarios radiant and/or suddenly dark. …

Who do you think you are?

If you’re a fiction writer, you know this question, because it hangs in the air every time you sit down to write a story. It doesn’t always come in such an accusatory tone, though. Sometimes it’s more like, Who can you be, believably, for the length of this narrative? Because that’s one of the freedoms of fiction: you can tell a story from the point of view of a newborn baby, a person from ancient Mesopotamia, the President of the United States, an envelope—anybody or anything. And it seems like all you have to do to earn that freedom is to inhabit that character convincingly, to make the reader believe that they’re really listening to an envelope talking.

Except sometimes the accusatory tone applies: Who do you think you are? Because let’s say you are a straight, cisgender, white male (like I am), and you decide to write a story from the point of view of a black man, or a woman, or two lesbians raising a son together, or any other character who isn’t a straight, cis, white male. At that point the question gets a little pointed.…

Newly returned from the Bosnian war, Buck Metzger can’t sleep. His waking life seems to be a mix of old and new nightmares, old and new dreams—some involving revenge, some involving pretty girls who live and breathe the ether of literature, and some just memories that float in the landscape of his mind like boats on the fresh water of lakes Huron and Michigan. North Dixie Highway is Joseph Haske’s debut novel, and it does not fail to beguile. The author starts his writing career with a bang, as the narrative is crisp and flowing, full of disquietude and searching, but also replete with fast-moving scenes of family life, war, old feuds, childhood haunts, infatuations leading nowhere, and the present-day meandering roads that the young narrator tries to sort through in his attempt to put his life back together.…

For James Baldwin’s many devotees, Jimmy’s Blues and Other Poems is representative of the American novelist and essayist we all know: the narrative voice in Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953) and the unabashed writer-activist of The Fire Next Time (1963). As we look back to what we know of Baldwin’s work and style, Jimmy’s Blues (2013) shows us the parts of his writing that have been overlooked: a poetic speaker, for instance, who brings blues and jazz into the sounds and stories of this collection. When Beacon Press published the first edition of Jimmy’s Blues in 1983, four years before Baldwin’s death, the majority of Baldwin’s readership did not perceive him as a poet. He was instead considered a strong, clear narrative voice and a witness to how Americans hated and loved one another. This collection is emblematic of the narrative flow Baldwin brings from his fiction and non-fiction into poetry; it is also evidence that as a novelist and poet Baldwin’s voice is always consistent.…

Claudia Rankine. Citizen: An American Lyric. Graywolf Press, 2014. 169 pp. $20.00, paper.

Six chapters into her latest book, Claudia Rankine writes, “It is the White Man who creates the black man. But it is the black man who creates…This endless struggle to achieve and reveal and confirm a human identity, human authority, contains, for all its horror, something very beautiful.” Beautiful, she writes, and I repeat it to myself. Again. Reading this moment in Rankine’s work, I feel as if I’ve earned something, as if she is finally offering me, the reader, the consolation I’ve hungrily and anxiously been waiting for since the book’s terse epigraph from Sans Soleil: “If they don’t see happiness in the picture, at least they’ll see the black.” But full consolation doesn’t ever seem possible or even desirable for the speaker, such as when the “new therapist [who] specializes in trauma counseling” answers her front door and yells at the speaker, “Get away from my house,” and, “What are you doing in my yard?” only to be chastened by the realization that this nonwhite trespasser is actually her new client. In consolatory reply, the therapist utters the ineffectual apology: “I am so sorry, so so sorry” to the silent speaker. Thus ends the first section of Rankine’s book. We realize that consolation never counts in moments when people fail to see you.…

Every so often, a photograph becomes more than the moment it captured. It’s yellowed from hanging on the wall of a chain-smoking aunt, or its edges are wavy from that time the basement flooded. These types of heirlooms are faded, worn, sometimes recolored or restored—like our memories of them. They take on a history, a weight of their own. And in saving them, and more importantly, in sharing them—in passing them hand-to-hand around the table amid reactions of reminiscence, laughter, and loss—we carry that weight together. We find strength. William Stratton’s debut book of poetry, Under the Water Was Stone, evokes this feeling, seating the reader at a table among friends sharing stories of struggles and triumphs. In a striking synthesis of voices, Stratton delivers poems that show immense tenderness, sorrow, joy, and above all else, strength.

These poems, and Stratton’s book as a whole, are fortified through the effective contrast of tones, perspectives, formats, and subjects both within individual poems and among the poems themselves. Arranged in five sections, “Family,” “Friends Beloved,” “Self,” “The World,” and “Home,” the structure of Under the Water Was Stone provides a frame without limiting flexibility. Poems about loss and family benefit from the contrast of love poems and lyric observations of the world—yet because everything fits into the sectional structure, even poems with very different tones or subjects support the work as a whole rather than seeming out of place.…

You don’t need to look far to find Jake Adam York’s posthumous collection Abide described as an elegy for the poet himself. For some, this may be a familiar tune, bringing to mind Larry Levis’s Elegy, also published posthumously and described similarly. But a careful reading of Abide rejects the urge to position York as the focus of the book’s attentions.

His project—an ambitious, career-spanning one, of which this book is merely the latest installment—is a series of elegies for the martyrs of the American Civil Rights movement. York’s attention to the individual martyr is what empowers the project beyond simple gesture and into heartfelt mourning: those who are elegized are named specifically—John Earl Reese, Medgar Evers, William Moore, among others—and their stories are given intimate, sacred attention.…

August Kleinzahler. The Hotel Oneira. Farrar Straus Giroux, 2013. 112 pp. $24.00, hardcover; $15.00, paperback; e-Book, $9.99.

August Kleinzahler’s most recent collection of poetry, The Hotel Oneira, is saturated with images of weather. More particularly, it is saturated with the often discordant prosody of storms and the audial images created through reverberations in the lulling patterns of rain. Kleinzahler’s poems present freakish, operatic movement as well as the gradual revelations of images/objects that wind and rain manifest. In “Rain,” we see and hear this effect, which reveals “M. Francis Ponge, exemplar of phenomenology / and the breathing of things” as if Ponge were a secret object himself, who waits to appear

until sufficiently dark, as if at the beginning of a show,

and with the sound of it the only sound.

…

might one begin to detect his outline in the rain,

like an image hidden in a picture puzzle,

slipping about, darting like a pike,

over the hoods and under the chassis of parked cars…

Erica Dawson. The Small Blades Hurt. Evansville, Indiana: Measure Press, 2013. 66 pp. $20.00, Hardback.

Erica Dawson’s latest book whirls us like a drunken line dancer whose skillful footwork veers in and out of formal composure and into wild, playful lines and dark truths. In many ways, the book follows the narrative of her first collection, but Dawson isn’t embodying that Big-Eyed Afraid speaker anymore. Her lines possess a palpable confidence, a “tendency to lead” that comes from years of experience as a formalist writer. Dawson can swerve between lines and still keep the beat. She is as comfortable quoting Shakespeare and Whitman as she is singing every word to “Wagon Wheel” at the top of her lungs, no matter if the song’s “spokes [have] spun the road enough.” In the crown of sonnets in “New NASA Missions Rendezvous with Moon” she creates lines such as “Where there is space, there is, no doubt, a death / In the afternoon.” The bodies in The Small Blades Hurt search for those little deaths because “each mission is a tryst.”…

Robert Gray. Daylight Savings. George Braziller, Inc, 2013. 113 pp. $15.95, paper.

Robert Gray is one of Australia’s most celebrated poets, but Daylight Savings, which consists of forty poems spanning his nearly forty-year career, is his first book to be published in America. At first I wondered how these poems would translate to my own experience, which has taken place so far from where the poems were written. References to his home country do abound; Gray touches on Australian culture and history, especially focusing on its landscape and unique plant and animal life (there are, indeed, kangaroos). But these poems are not limited by their geography. They boil down to the essentials—nature, death, art, love—in a way that reaches far beyond their context.…

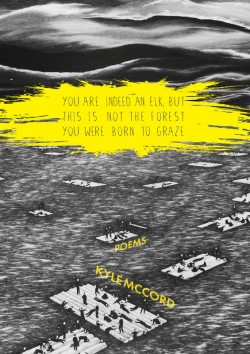

Mikko Harvey: The poems in You Are Indeed an Elk, But This is Not The Forest You Were Born to Graze harness the energy of narrative but are not, it seems to me, stories in any traditional sense of the word. They frequently digress and redefine themselves. I think this combination—a sense of moving toward a narrative ending, but exploding outward in the process—is what makes the book, strangely (strangely because the term is rarely attached to poetry), a page-turner. The humor helps too. Did you plan to write such a fun book, or did it just come out this way?

Kyle McCord: I’m glad you brought up fun because fun sometimes feels like the unacknowledged middle child of poetry. It has to ride in the backseat of the van behind Truth and Beauty who spilled milk in one of the cup holders. It has to hang out in the basement because Beauty is always hogging the bathroom, and Truth locked herself in the study.

The subject rarely commands page space in major lit mags either; I checked (just to avoid libelous claims), but there is no “The Art of Fun” coming out from Graywolf. But because I studied in an MFA program that emphasized irony, satire, mimesis, the reuniting of seemingly estranged dialects (commercial, romantic—big or little “r”—philosophical), all of which I think are fun, I treasure poems that are willing to risk irrelevance for the sake of play. I love Carroll, Dickinson, Tate because they aren’t afraid to be silly, to screw around on the page and see what you as the reader do.…

Michael Mlekoday’s first book, The Dead Eat Everything (Kent State University Press, 2014), was chosen by Dorianne Laux as winner of the 2012 Stan and Tom Wick Poetry Prize. Mlekoday serves as editor and publisher of Button Poetry / Exploding Pinecone Press, is a National Poetry Slam Champion, and has work published or forthcoming in The Greensboro Review, Salt Hill, Banango Street, The Pinch, and other venues. His poem “Flood” appeared in The Journal issue 36.3. He recently spoke with poetry editor David Winter about his writing process, rap, race, and what it’s like to write a book-length poem.

David Winter: The Dead Eat Everything includes thirteen “Self-Portrait” poems, each written in a different mode. Your ability to examine the self from so many different angles, to continually mine it for imagery and music, is one of the driving forces of the book. What did the process of writing those poems look like for you?

Michael Mlekoday: At first, I didn’t really know I was writing a series. They were just individual poems, to me, and not all of them were initially called self-portraits. But I had been living in the world of some of these poems for a while, and I started to see that they were all interested in the way the self is constructed—by culture or society or whatever. I liked the idea of self-portraits that begin with the external, the outside world, and work their way back.…

Ray McManus. Punch. Spartanburg: Hub City Press, 2014. 72 pp. $15.00, paper.

From the cover photo to the opening epigraph, we know that this is a book devoted to the life of a working man. Punch is a distinctly American book in that way: it contains the poetry of a man destined to change water in a field, to wrestle with barbed wire, to know the hours put into the job because there’s a piece of cardstock with his name on it as well as the days of the week, which he punches every morning and then again every night.…

Adrian Matejka. The Big Smoke. New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2013. 128pp. $18.00, paper.

Adrian Matejka’s third poetry collection, The Big Smoke, dramatizes the physically grueling, racially charged, and ethically complex boxing career of the first African American world champion, Jack Johnson. With the exception of the closing poem, the voices of Johnson and his supporting players tell their own stories. For Johnson, that act of gaining sovereignty over the literary representation of his life substantiates his masculinity and his contested humanity. Early on, the reader will notice the subtle accumulation of the phrase “they said” in various forms. Johnson recognizes that his image, constructed by hands other than his own, fuels a corrupt campaign. That fabricated image corroborates a racist ideology that refuses to identify people of color as intellectually sound and morally upright individuals. If Johnson is indeed an inherently deviant beast, then the world can devalue his greatness as a boxer and negate his human status; it does not have to undertake the mentally strenuous mission of examining its belief systems.…

Benjamin Miller. Without Compass. New York: Four Way Books, 2014. 72 pp. $15.95, paper.

In Benjamin Miller’s engrossing debut, his speaker lives in what one title calls the “Wake of Avoidable Tragedy.” I hear only one speaker, because the voice is so consistent from poem to poem. Stuck in a psychological desert, he occasionally doubts that a way out exists and feels as if he’s without a compass. More often, though, he’s aware that his compass may be broken, pointing in the wrong direction. Or that he can only properly use the working device—know where to go and why—after honing his ability to exist in uncertainty, what Keats called negative capability. “One-eyed crabs clung to my fingers,” he says, “And I named them. This is wait. This, delay.” He puts the thing away to be intentionally without compass but then glances at it from time to time. Eventually, he trusts it.…

Ruth Ellen Kocher. domina Un/blued. North Adams, VT: Tupelo Press, 2013. 81 pp. $16.95, paper.

Ruth Ellen Kocher’s fourth book, domina Un/blued is an austere, surreal, imaginative exploration of historical servitude, dominant/submissive relationships, and found/lost personhood that poet Lynn Emanuel justly selected to win Tupelo Press’s coveted Dorset Prize. Often, modern readers of poetry seem to approach a book as if the text must prove itself to the reader, as if it must offer itself up and unspool meaning in accordance with the reader’s preconceived conventions. Such an approach will be unsuccessful with domina Un/blued. One must, rather, offer oneself up to this work.

domina Un/blued is, for Kocher, “an experiment in palimpsestic writing” built upon/through fragments of two earlier manuscripts, Hybrids & Monsters and The Slave’s Notebook. In reading domina Un/blued, the notion of palimpsest comes through in several poems interrogating the act of translation, where the poem itself is a footnote to an exercise that is white space. In “D/domina: Issues Involving Translation,” the poem appears as white space interrupted only by footnotes at the bottom of each page, such as: “Exercise 3. / Possessive case for the word ‘slave’ does not exist in Italian. // The slave owned not own nor owns / Nor evolves. Nor provision any make consonant belonging.” Thus, even within the footnote to the white space, Kocher uses extended spacing between words to highlight the erasure inherent in the (dominant) enacting of translation. In “Translation Exercise Esercizio di traduzione,” Kocher creates a poem from two parallel columns of text, one English and one in Italian, both offering translations of the same line. For example:

| it is hot | è caldo | |

| warm | caldo | |

| blazing | sfolgorante | |

| the handcuffs begin with me | le manette iniziano con me | |

| i am the lock and the key | io sono la chiave e lo schiavo |

By structuring her poem in this way, she permits—even encourages—readers to subvert the dominant linear reading of texts in favor of a more fluid, multiperspectival approach, where one could read the English column then the Italian column, or the English line then its accompanying Italian line before moving on, or, depending on one’s fluency and desire for language as sensual sound play versus meaning-making, one could move across these columns at will, without linear order.

While multiple poems involve Italian words, sometimes with translation (as above) and sometimes without, readers need not be fluent (or even familiar) with Italian to experience the impact of Kocher’s writing—one need only be open to loosening the quest for meaning (which is, perhaps, a quest for dominating) into a sensual receptivity to the pleasures of music. In “Translation Exercise II,” the lines “Some people I sweet delicate who would aggressively / animaleschi who would elegant refined who would sport,” and “I assure you that I like the game and fun the transgression me / irresistibilmente,” are amplified by the inclusion of Italian—which subverts the dominance of English even while offering readers word roots (“animal” and “irresistib[le]”) that make them participants in this elision of language.

Furthermore, Kocher’s use of white space is provocative throughout. In most of these poems, each present stanza is separated by enough white space to hold traditional stanza-break space plus an absent stanza, forcing readers to read absence as a presence and to submit to a magnified version of the delayed fulfillment we experience in stanza enjambment—a fine illustration of dominant/submissive relationships through both form and content.

Kocher’s background in classical literature and linguistics is apparent in this text, for she frequently returns to the Corinthian column (iconic structure of empire and civilization) and the theory that its design was inspired by a basket of acanthus leaves placed on the grave of a slave girl. “Un/blued” features three identical columns of text that begin: “the columns are / capped with / acanthus,” then repeat down the page “empire Empire / E/empire / empire Empire / E/empire,” before terminating in “baby, baby, o / baby / girl.”

Linguistic play abounds in works such as “D/domina’s Feet,” where Kocher writes, “These woods [period] All Woods [period] No / matter / How hard ‘All / Woods’ desires to be only wood all woods is all / woods.” In “D/domina,” Kocher uses transgressive capitalization to explore dominant/submissive relationships:

sorry to request

sorry to Y/you to be unworthy

(this morning on the train Y/you show M/me that Y/you are)

(this morning on the train Y/you yolk as uniform as the egg’s shell)

i thank Y/you again

(the egg knows an order)

In the poem “Translation Exercise,” Kocher writes, “i am the slave and the key / the keys / i belong to / my self not my sex.” Speaking from a personhood where “Possessive case for the word ‘slave’ does not exist in Italian,” one must conclude that, since “black is only a thing the slave owns that is nothing,” the slave cannot even own the capital I. As an African American poet, Kocher’s astute exploration of historical servitude has significance for European and American readers.

Beyond Kocher’s complex theoretical and philosophical underpinnings, the musical, lyrical language glimpsed in her earlier books is vibrant and electric here. In “D/domina: Daughter,” she writes, “and within that conversion / your loss as a first nothingness.” In “D/domina: G/gnosis,” she weaves together image and lyric: “Her body / hid from its parents Forgot its sisters Bathed / each morning as though performing ritual // leaving Her body knew before she knew / Soon like hesitation It would forget return.” Repetition of sound and image works to evoke almost pre-lingual reverberations within the reader, again using language to destabilize itself, as in “D/domina: Look,” where readers find “grass nearby cut and clumped. grass clippings. grass smell. grass / green and gasoline. engine. night / streetlights come on // say night come on.” And, in “M/meditation I Dominance,” the poem subverts our expectations of agency by exploring the voices of temporal entities—those we may more often see as spaces for action, not as actors themselves: “The once has never said / Nor the next day stammered.”

In a world dominated, at times, by three-section manuscripts, Kocher’s choice to offer her collection without section breaks is effective. By doing so, she reaffirms the slipperiness of language, domination/submission, and identity—for can a poet ever say where one section’s themes/motifs end, with certainty? Can a poet’s work, which often arises from a swirl of influences lived, imagined, and co-constructed, be that easily partitioned? Such an act may be reductive, forcing the text to submit to reader expectations, and domina Un/blued, fierce in its beauty, will bow to no one.

And, as in her earlier books, Kocher proves that she knows how to close a collection, powerfully, in her last lines:

There is no field. There is no clover no green. You listen

anyway. Hear a voice follow you into the afternoon Language

crosses a clearing the stark way a thing revealed

when thinned clouds expose better light.

You the tree tip toward words as they bring outward

inner form.

In domina Un/blued, Ruth Ellen Kocher establishes herself as a sophisticated writer who holds a command of image, syntax, and line, even as she invites the text to de/stabilize this authority. What, then, can readers do, but submit to this destabilization as well?

Tessa Mellas. Lungs Full of Noise. Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Press, 2013. 133 pp. $17.00, paper.

The twelve stories that make up Tessa Mellas’ debut collection, Lungs Full of Noise, are absorbing, haunting, and unforgettable. The collection, which won The Iowa Short Fiction Award, is darkly fantastical and delightfully strange, calling to mind the works of Angela Carter, Kelly Link, Karen Russell, and Kevin Wilson. The stories feature a leaf-covered baby with vines sprouting from his body, figure skaters who affix ice skate blades directly to their feet, a green-tinted college roommate from one of Jupiter’s moons, three young girls stranded in an attic by rising sea levels, and teenage girls who eat nothing but grapes so they can dye their skin lavender to attract prom dates. Mellas’ prose is lovely, precise, and surprising; she takes no shortcuts and doesn’t rely on familiar tropes or clichés. Each sentence, and each story, is original and unexpected.

Although there is a lightness in the lyrical language and playful humor that runs throughout this collection, these stories have heft. They are concerned with issues of self-doubt and insecurity, ambition, jealousy, fear, loss, powerlessness, control, grief, and unfulfilled longing. Themes of troubled motherhood and the confinements of femininity appear again and again. Several stories address the deteriorating environment and the impending apocalypse. The stories also show a preoccupation with the body, examining the ways in which people try to manipulate their bodies, the ways in which our bodies betray us, and the body’s mysterious hungers.

The characters that inhabit this collection are often overwhelmed and outmatched by their desires, and the stories explore the ways in which their misguided attempts at fulfilling these desires go awry. In “So Many Wings,” a woman named Bea discovers that her ex-husband died in a car accident and steals his severed arm from the morgue as she is identifying his body. When she unwraps the arm back in her apartment, “it makes her body feel buoyant,” and she falls asleep with the arm tucked into the sheets of her bed. In “The White Wings of Moths,” a mother longing to make things right with her estranged daughter fills her home with thousands of caterpillars until the house becomes overrun with moths. The moths “coat the walls… Around the chimney, they huddle en masse. They smooth the chimney’s edges out. They bulge, a tumorous growth, a snowy beast… [Bea] unearths a cocoon. A cocoon the size of a daughter.” In “So Much Rain,” three sisters living in the top floor of an abandoned house during an apocalyptic flood struggle against their inevitable end, eating Polaroid squares and wallpaper and crayons, calling each other names and playing nonsensical games. Unable to understand, accept, or change their circumstances, Mellas’ characters follow their own flawed and desperate logic.

For me, the standout story was “Bibi from Jupiter,” in which the narrator moves into her college dorm to find that her roommate hails from one of Jupiter’s moons. “When I marked on my roommate survey sheet that I’d be interested in living with an international student,” the story opens, “I was thinking she’d take me to Switzerland for Christmas break or to Puerto Rico for a month in the summer. I wasn’t thinking about a romp around the red eye of Jupiter, which is exactly what I’d have gotten had I followed my roommate home.” The narrator’s sarcasm and sharp wit are flimsy covers for her insecurities and hurt, and the reader learns about Bibi through jealous and guarded descriptions. “She’s not an all-out green,” the narrator explains. “Tinted rather, like she got a sunless tanner that didn’t work out. Her ears are inset like a whale’s, and she doesn’t have eyelids.” But Bibi is smart and popular, especially with the boys living on their hall, and the two girls’ relationship becomes complicated and fraught. The narrative deftly delves into the unexpected, but the outcome still seems inevitable and fitting.

Another favorite, “Quiet Camp,” about a camp for girls who talk incessantly, is breathtakingly lyrical and immensely moving. It begins, “We arrive on a westerly wind, our lungs inflated with speech. Our mothers said this would happen if we didn’t learn to quiet our tongues. Our tongues couldn’t be stopped, so up we went. Up and up. Until we knocked the chandeliers with our heads.” The story, told from the collective perspective of these chatterbox girls, follows the girls’ attempts to quell their natural proclivity for constant speech, and the harsh punishments they receive when they fail to do so. The descriptions of their time at the camp are evocative and lovely: “A rowdy tribe, we walk through the woods…The sound of our speech swarms like the hiss of cicadas thrashing out of their husks. Syllables tap off our teeth. Our dimples crease and uncrease in a Morse Code frenzy.” Told with the peculiar mix of grotesque hyperbole and dark beauty characteristic of fairy tales, this story left me unnerved but enchanted.

These stories are unsettling. They work themselves into your mind and climb under your skin, and they linger. Mellas’ characters are eccentric but wholly convincing, and it’s difficult not to feel the full and devastating weight of their vulnerabilities, wounds, and desires. These stories relentlessly examine the weakness of the body and the desolation of a future where the world’s resources have dried up. They lead the reader far into the realm of the impossible and the strange to expose the familiar in a new and harsh light. But buoyed by the beauty of the language and the wonder of these unexpected narratives, this collection is captivating. This is an important, intelligent, and mesmerizing book, one that establishes Mellas as an original and unflinching writer.

Jamaal May. Hum. Farmington, ME: Alice James Books, 2013. 74pp. $15.95, paper.

Jamaal May’s self-reflexive debut, Hum, is musically understated, performative yet private, a spiritual voice in dialogue with a post-industrial landscape. “Dedicated to the interior lives of Detroiters and the memory of David Blair,” the book takes its formal structure from the combination of that landscape with the speaker’s anxieties, which range from the mundane to the mortal. But ultimately, the book invests the word “hum” with a particular sense of the human, a spiritual music that finds its way up from between May’s words and defies straightforward analysis.

The book opens with a poem entitled “Still Life,” an anaphoric series of images of a boy costuming himself and playing imaginatively with urban detritus ranging from barbed wire and bent nails to a bath-towel cape. The end of the poem takes an inward turn with the lines, “Boy with a boy / in his head kept quiet / by humming a lullaby / of static and burble.” The first of many references to “humming” throughout the text, one might read these lines as a self-portrait or analogue of the author as a young man and a description of Hum’s nascent project. But only a few lines after this framing of the poetic text as personal solace, that project is placed in jeopardy. May writes of rust as a metaphorical thief the boy “doesn’t see / but knows / is coming tomorrow / to swallow his song.” This tension between the transformative potential of creativity and the consumptive action of time seems central to Hum, underlying the anxieties that structure the text.

May’s marriage of interior life to external form is unusually intricate, particularly for a poet’s first book. Many poets have used the sestina, a traditional Italian form in which lines end with particular words that repeat according to a mathematical pattern, to explore themes of obsession or anxiety. The second and second-to-last poems in Hum are sestinas that share a single set of end-words: “machine,” “ignore,” “sea,” “snow,” “needle,” and “waiting.” Six other poems in the body of the manuscript take their titles from phobias associated with those end-words. Such ambitious projects often come at the expense of attention to individual poems, but the eight poems of Hum’s spine each feel as carefully conceived as the overarching structure itself. “The Hum of Zug Island,” the book’s second sestina and penultimate poem, even earned May a Pushcart Prize. However, the function of these formal devices is not simply to impress; they build the themes of obsession and anxiety into the structure of the text itself.

Though subjects such as “snow” and “waiting” may seem rather mundane foci for phobias, in May’s poems these subjects become pathways through anxiety into trauma, raising questions that resound long after the poems end. “Chionophobia: Fear of Snow” is a second-person elegy in which we know the deceased protagonist only as “you.” In the poem, the windblown ash and sand of a combat zone recall the snow in which “you” and “your brother” played as children:

Can two snowflakes be the same

on a ghost-white street where enough gather

to construct faceless snowmen? In this desert,

sand blinds the way snow did back home.

Your brother patches holes

in men with names he can’t or won’t learn,

and wonders if, somehow, you are still here,

using an earthmover to pour sand

into foxholes.

These lines highlight the particularity of the minute and familiar—snowflakes, grains of sand—while also pointing out the anonymity of bodies in war. How can snowflakes be unique when survival seems to depend on blinding ourselves to the individuality of the suffering and dead? Images of “your brother” and “you” patching and filling holes may gesture toward healing and peace, but the comfort they provide restores neither the identities of the soldiers nor the landscape.

The poem continues, weaving meditatively between images of past and present, sand and snow, before arriving at the apparent source of the protagonist’s fear. When a fruit stand appears to shiver in the desert heat, “your brother” recalls how his family heard the news of “your” death:

Your brother shivers

remembering your mother’s shiver,

the way she sank to the ground, heavy

with news, and your body comes home again.

Your bone-colored casket repeats

its descent, sinks under the flag, and a thud

resounds. Fades. He still hears it.

In these lines the poem’s dichotomous elements blur together, resolving momentarily into a scene where sand and snow, innocence and mortality, the living and the dead all coexist paradoxically. The leaping progression of images through which we arrive at this transcendent moment not only makes rhythmic and resonant connections between disparate settings, it also reflects the fact that post-traumatic stress is often triggered by seemingly innocuous experiences.

Such associative leaps are common in May’s work, but they seem particularly suited to describing the dissociation experienced by this poem’s speaker. In the final lines of “Chionophobia: Fear of Snow,” May capitalizes on this dissociation as well as the second-person mode of address to enact the protagonist’s identity crisis on the reader: “Deafening like footfalls / against the icy driveway, resonant / like your mother’s voice, calling / the wrong name—your name—again.” The ambiguity of identity in these lines shifts attention from the protagonist’s grief over the trauma of his brother’s death to the realization of his own mortality. And this artful closing completes the poem’s journey from a phobia’s innocuous trigger through personal trauma to the temporal source of so many obsessive anxieties.

While this review has focused on how the poems that act as Hum’s most explicit structural elements explore the speakers’ anxieties about time and mortality, the other eighty percent of the text also deserves critical attention. The images and themes introduced in the sestinas and phobia poems recur throughout the book, adding to the impression of anxiety while re-contextualizing key words and images in surprising ways. As mentioned above, Hum is intimately concerned with Detroit’s post-industrial landscape and legacy, and several of the poems explore relationships between humans and machines in terms that are both spiritual and bleakly realistic. In “Hum for the Machine God,” a title which plays on the word “hymn” as well as other meanings of “hum,” a boy prays for his abusive father to be injured but feels remorse when his prayer is granted more brutally than anticipated. In “On Metal” a handful of lay mechanics huddle around a broken down car as the speaker realizes that the human body and the tradition of mechanical repair—both of which he reveres with a nearly religious sense of mystery—are rapidly being rendered obsolete by computerization. And in “Hum of the Machinist’s Lover,” a machinist serenades an automaton he’s created, but whom his breathing corrodes. In these poems, the speakers’ anxieties about mortality intertwine with spiritual tradition and technological innovation to render a portrait of the human condition during a distinctly postmodern moment.

May intricately weaves together these themes and others to create a wide-ranging and surprisingly coherent debut. But what makes Hum remarkable, perhaps more than its structural sophistication or thematic content, is the intimacy and authenticity May’s voice conveys as he thinks and feels his way through each line and stanza. In “Thalassophobia: Fear of the Sea,” a poem addressed to the Detroit poet David Blair who drowned tragically at a young age, May writes:

. . . You know

I get like this sometimes—I listen

for footsteps that will never come,

remember waves I’ve never seen,

watch them fold and break and slowly

whet stones that jut up from coastlines,

and today I learn something old

about the sea . . .

In these lines May makes himself vulnerable by sharing his creative process—a process of discovery in which imagination blends with memory and sensual perception—with someone he loves. And while not all of the poems in the book exhibit that process as explicitly as “Thalassophobia,” an impression of May’s vulnerability suffuses his poetry. Formal sophistication and conceptual implication may make Hum a significant work of literature, but it is May’s human touch that fills these poems with the irreducible combination of feeling and music.