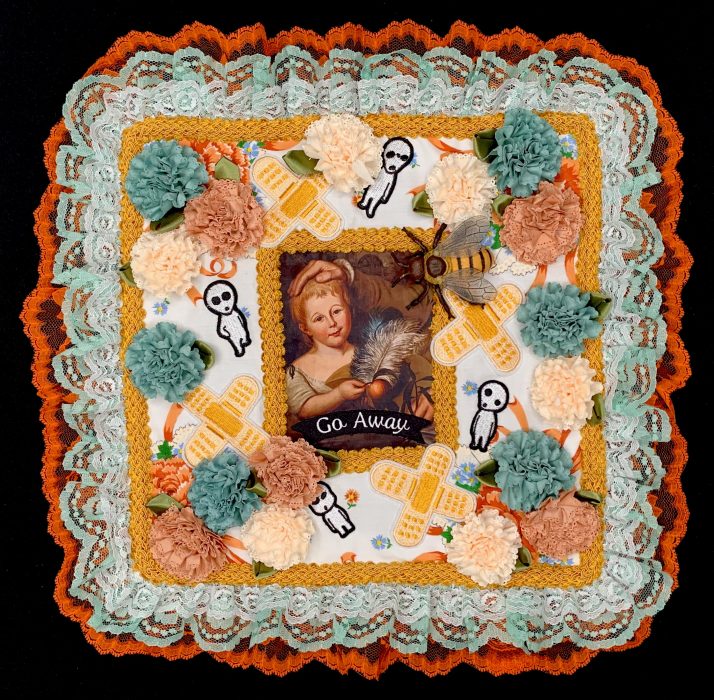

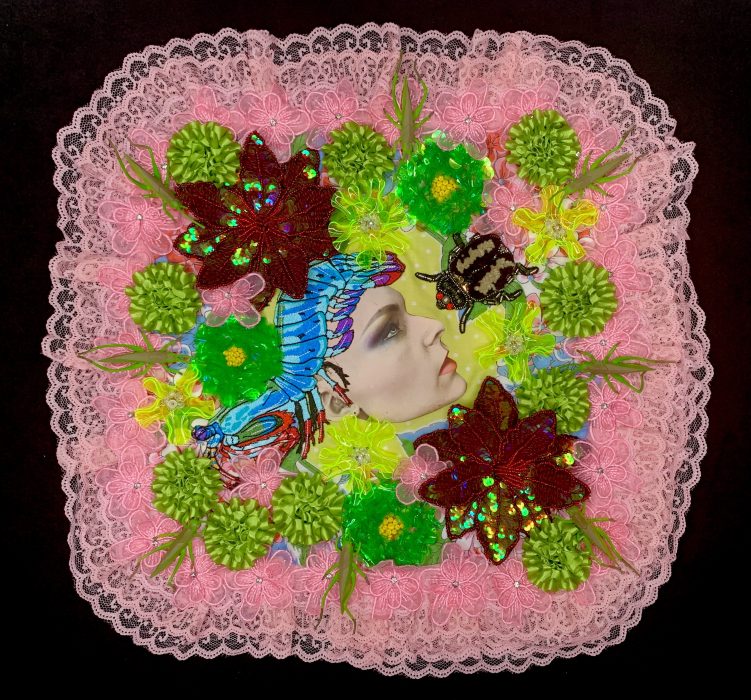

K. Johnson Bowles’s series Veronica’s Cloths balances the grotesque and the beautiful, the kitschy and the transcendent, and it’s a balance as delicate as the lace they’re sewn into. If at first glance her collages look like a throw pillow from your grandmother’s attic, please take a closer look, and you’ll find something creepier and crawlier lingering under the surface. Art Editor Morgan Fox and Associate Art Editor Arah Ko talked to Bowles about the layered complexities of the Cloths.

Morgan Fox and Arah Ko: Could you tell us a little bit about your process? What goes into making a cloth in this series?

Johnson Bowles: Each piece begins with an aesthetic pairing of a vintage handkerchief and a photograph. The photographs are ones I’ve taken of objects found in museums, cemeteries, or antique stores. The images depict compelling details of paintings, sculptures, and sometimes kitsch oddities. For me, each image triggers memories of and emotions associated with an experience.

A themed composition emerges from an iterative process of juxtaposing and layering materials and objects such as appliqués, lace, upholstery trim, flowers, buttons, beads, feathers, and plastic insects, snakes, and body parts. I source materials from anywhere and everywhere – Amazon and eBay to the NYC garment district and junk stores. Language, symbolism, and metaphors play a prominent role in the development of a piece. The almost Dadaist, Surrealist, Abstract Expressionist free-form process emerges as a visual poem for me.

Then, I photograph the composition for reference and plan out the actual construction to determine which layer is applied first, second, third, etc. The vintage handkerchief is washed, starched, and backed with cotton fabric. The photograph is digitally printed onto a heat transfer paper and ironed onto the cloth. Next, layer upon layer of materials is hand-sewn onto the fabric. Hand sewing can be an arduous process. Sometimes I have to create holes in objects with a power drill or awl to be able to use a needle and thread. Sometimes the layers are so thick I use a needle-nose plier to pull the needle and thread through. I experience the process as a sort of meditation or devotional.

Keeping Your Head/Losing Your Mind

AK: What first drew you to work in fabric? As an artist who works in many mediums, is there anything about cloth that you feel is often misunderstood?

JB: The numen associated with fabric fascinates me. Throughout time and various cultures, fabric possesses a powerful position in ritual, spirituality, divine intervention, folklore, and the cult of personality. Think about the Shroud of Turin, Egyptian mummies, Little Red Riding Hood, and the enshrinement of clothes worn by the famous and infamous in museums – Marilyn Monroe’s white halter dress, Michael Jackson’s single glove, and Michael Jordan’s sneakers. The panoply of human experience is embedded in fabric – a school uniform, a wedding dress, a soldier’s uniform worn in combat.

My previous series, including Post Catholic Relics, Wearing a Woman’s Life, For Better or For Work, and Mixed Messages, all included fabric. Unfortunately, many of these works were misunderstood. The religious right protested Post Catholic Relics in the early 1990s. (In one piece, I enshrined a pair of menstrual-stained underwear). Wearing a Women’s Life provoked numerous editorials in the late 1990s (people didn’t want to see the hospital gown I delivered my daughter in). Even Veronica’s Cloths sometimes is mistaken for a “pretty pillow” until the viewer realizes each piece is an uncanny valley.

Classifying fabric in the hierarchical taxonomy of art materials represents a problem for most people. Fabric is a craft, a hobby, and a highly gendered material. Fabric is low brow in the fine art world. That’s why I use fabric to express discrimination and social justice issues – to turn perceptions upside down. I’m not interested in using materials and a hierarchy associated with white male power and privilege.

Last Laugh (Earwig)

Losing Face/Faith

MF: The Catholic imagery in these pieces really stands out, but it’s a symbolism that’s fractured, sort of “remixed” with much different imagery (the spiders, the lace, etc). Could you talk a little about that juxtaposition between the religious and the secular?

JB: Being Irish Catholic is a heritage, not a practice for me. It provides a rich visual vocabulary via symbolism rather than a belief system rooted in Biblical stories. For example, I’m more interested in the beautiful and terrifying mythology found in images depicting the lives of saints. Seeing pictures of a perfectly calm St. Agatha holding her own severed breasts or St. Lucy holding her own disembodied eyes on a platter is striking. Images like these on prayer cards became seared into my mind as a child. It’s a disturbing, insane, ridiculous, and yet weirdly effective way of illustrating perseverance and faith. It is dark and over the top; I’m fascinated, shocked, and amused simultaneously.

Contemplating how myths and folklore can be reimagined or reinterpreted from a New Materialist, feminist, and social justice perspective occupies a large part of my thought process when creating an artwork. I ask what does any image mean? How are memories and ideas triggered by details of objects remixed into a new whole?

Materials and imagery associated with sweetness and stereotypical gender performance lure the viewer. Upon closer inspection, the piece includes phobia-laden objects and suggests fear, terror, anguish, anger, and violence. Combining the two elements leads the viewer to conclude the meaning isn’t so ‘nice’ at all; it is profane.

Mantis Mind v. Beetle Brain

MF: In your statement on the series you mention that each cloth is hand-sewn in a way that suggests a “grandmotherly” quality. I’m really interested in how the grandmother archetype plays out in the pieces, given that in fairy tales the grandmother is both the wise and caring figure but also the mysterious and often menacing figure of the crone. What is important about the grandmother quality to you?

JB: I love this question. You rightly point out that archetypes play roles in Veronica’s Cloths. Both the grandmother and the crone take stage via the materials and the content. Sometimes it’s a monologue and an unveiling of the types: the grandmother offers words of strength, advice, or comfort amid challenges, or the crone slyly presents a real threat, much like the offering of a poison apple to Snow White. Sometimes the crone is disguised as the grandmother to deceive like the older woman in the story of Hansel and Gretel or the wolf in Little Red Riding Hood. Other times there are battles between the two archetypes, more like the good witch of the North and the bad witch of the West in The Wizard of Oz.

Veronica’s Cloths presents the narrative of experience and trauma, resilience and tenacity, and good versus evil. They are instructional and reflective. I use a ‘grandmotherly’ aesthetic to set a tone and afford access to pain and injustice. It is often challenging to speak about the terrible truths of personal experience without the viewer becoming uncomfortable and turning away. When I think of grandmothers, or more precisely women of a certain age, who are past childbearing years and society no longer sees them as objects of desire or even a physical or intellectual threat, I think about the strong women I know. Most have experienced trammels and profound life challenges, which have made them wiser and tougher than most people would expect. They are at the point in their lives where they don’t care what people think anymore. They may look sweet, but they also will tell you in no uncertain terms when to go to hell.

Neither Here Nor There

MF: You also talk about this series as being rooted in social justice. Could you elaborate on that?

JB: Several years ago, I experienced threats, harassment, assault, discrimination, retaliation, and defamation in the workplace. Not only was my well-being in jeopardy, but my core values were at stake. So, I had to choose between justice and my job. I sought justice, and it has been the most challenging journey in my life – literally a David versus Goliath battle that’s still not over.

The series began out of a need to do something to combat my profound despair, anger, disbelief, and loss. I wish to reclaim my voice, express my thoughts about what I experienced, and find a way to heal. I hope it brings to light what many women (and underrepresented people) have unjustly experienced in the workplace at the hands of both men and women in positions of power and privilege.

No Kisses From All and Sundry (Insecticide)

MF and AK: Do you have anything exciting coming up?

JB: I’ll continue creating new pieces in the series with a goal of producing a book of the images. Thus far, there are 100 works in the series. Nearly all have been published or are forthcoming in art and literary magazines across the U.S. and Canada. I’m also working on a book about embodied color based upon my forthcoming essay, “The Color of Trauma,” published in the June edition of Afterimage (UCPress).

There Will Be Lies

K. Johnson Bowles’ artworks focus on issues of identity and sexual politics and have been featured in more than 80 exhibitions and 60 publications. She has been awarded fellowships from the NEA, Houston Center for Photography, the Visual Studies Workshop, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Art. She received an MFA from Ohio University and BFA from Boston University.