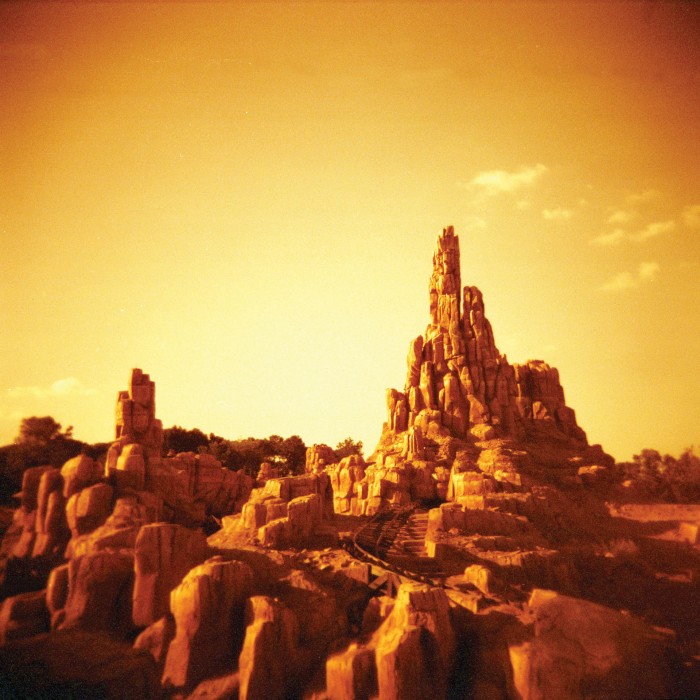

Charlie Wagers seeks weathered textures, bright contrasting colors, and strikingly ordinary subjects. He finds these things tucked away in forgotten places of the United States: on a roadside in Kentucky, a block of abandoned homes turned into an art exhibit in Detroit, and a shore in North Carolina where vacation homes are falling into the sea. He captures places that tell unusual stories despite seeming so common as to be embedded in American identity. His images often symbolize loss and are made by using outdated, “lost” technologies. His favorite is a plastic toy camera. Charlie spoke with Associate Art Editor Janelle DolRayne about his experimental processing, working with your hands as a designer, and the effect of applications like Hipstamatic and Instagram on photography.

JDR: Can you tell us a little bit about the medium and your process?

CW: These particular images were shot on analogue 120 films, using square-format, plastic-lens cameras. The cameras themselves are very minimal tools made out of cheap plastic and typically don’t even include a flash. The cameras are known for their loose seams, which cause the light leaks that everyone loves. The uniqueness of the medium comes from an array of experimental techniques used, like cross-processing the film, which is essentially developing the film in the wrong chemicals on purpose. Following the “Don’t think, just shoot,” technique, combined with the analogue equipment and unorthodox processing methods, results in images filled with saturated colors, off-kilter exposure, blurring, and other happy accidents.

JDR: How do you decide how you are going to process a roll of film? Is it mostly experimental play? Do you choose techniques based on what you shot? Or is it some combination of both?

CW: It’s mostly experimental, and even random. I’ve found that cross-processing E-6 usually causes the image to darken a little. So I’ll take that into consideration, but I almost always cross-process E-6, because it pushes the colors into an unpredictable spectrum. My favorite film is Fuji Provia, which, when cross-processed, turns all blues into turquoise. Right now I’m experimenting with a new infrared “purple” color-negative, similar to the discontinued Kodak Aerochrome. This type of film was originally designed for surveillance applications to help differentiate camouflaged objects. As a result, it changes all of your greens into a bright purple color.

JDR: As a graphic designer and illustrator, what draws you to medium-format photography?

CW: My design work is my primary focus, as it’s my profession and source of income. My interest in medium-format photography started with a desire to incorporate the photographs into my design work and became my preferred way to capture the world around me. I also incorporate screen-printing into my work, as I have a strong interest in old technologies. The computer is a Lite-Brite for bad ideas, and I’m always looking for new ways to work with my hands rather than look at a screen.

JDR: Can you talk a little bit about how design can be negatively affected by the “Lite-Brite” and the benefits of working with your hands with older technology?

CW: Form follows function, and it’s easy to forget that when constantly working on a computer. I’m intrigued by past designers who generated ideas and solutions while using limited resources. I do screen-printing because it’s an exercise in limited color, figuring out how two colors can work better than four. There’s a lot to learn from photography, typography, and design that was done before computers, digital-cameras, and Adobe products changed the industry.

JDR: It seems like anyone with a smartphone can make an image look “vintage.” How have you responded to technology and applications like Instagram and Hipstamatic that mimic medium-format photography?

CW: I’m definitely guilty of using Instagram more than any other application on my iPhone, but it’s also not my preferred camera. Anymore, it seems like all of your friends (and maybe even your parents) use Instagram, filling the app with oversaturated photos of non-photogenic things (see: “selfies”). The filters can be used in a way that produces a worthwhile image, but they’re usually heavy-handed and gimmicky. The resulting image is only part of the process; it’s about feeling the camera in your hands, loading and unloading the film, and the fear of accidentally ruining the entire roll.

JDR: Do you think these “gimmicky” Instagram images are negatively affecting the merit of or desire for authentic medium-format photos?

CW: I wouldn’t say that Instagram is cheapening actual photography. In fact, Hipstamatic has little built-in “films” which are an ode to the process. I can’t deny that medium-format photography takes a lot of practice to get used to and is not for the faint of heart. Also, I can easily tell the difference between a real square-format photo, and one that’s generated on an iPhone. You can tell when the photographer has gone the extra mile to make a memorable image.

JDR: In this series we see a lot of images that deal with decay and forgotten, desolate places. What interests you about your subjects? What compels you to point and shoot?

CW: I mentioned before having a strong interest in using old techniques to make art, and these subjects are linked to that interest. Screen-printing and letterpress are famed for the texture they leave on paper. Even if I’m just working digitally, I often generate a similar effect in my work on-screen. I love the combination of faded and weathered subjects, as seen through a colorful, contrasting lens. I use a lot of texture in my illustrations, and so I’m always interested in photographing textured things. I’ll manipulate these textural images to be used within my digital work.

JDR: Do you think your interest in these places and technologies is connected to your upbringing on Kentucky farmland?

CW: Absolutely! I spent most of my childhood outside around old, rusty tobacco-farming machinery. My family didn’t have the Internet until I was a teenager, so rather than looking at images online, I gained a particular aesthetic from my surroundings.