Landscapes is set in a future of environmental collapse that, while fictional, feels grimly easy to imagine. “A nature diary composed over the past decade would read like a catalogue of losses. There was a time when catastrophe seemed far away…then change became visible,” the novel’s protagonist, Penelope, tells us in the opening chapter. Penelope is the archivist of Mornington Hall, a formerly grand estate that has succumbed to decay along with the world around it. But as the novel begins, most of Mornington’s prestigious holdings have been either destroyed, damaged, or sold to finance repairs. The estate’s house, gallery, conservatory, and library are set to be demolished seven months from the book’s onset. The novel is a record of that time, partially composed of Penelope’s diary entries and catalog notes as she archives what remains of Mornington, which has also been her home for the past twenty-two years. Penelope’s archival notes are just as personal as they are professional—perhaps more so: “I also wish to keep a record of the objects that I find evocative, with a description of their physical states as they exist now, in my hands,” she writes. Indeed, Landscapes is ever-conscious of the ephemeral nature of art, and our particular experiences of it, often belied by the facade of conservation: if art can be preserved, restored, contained, can we protect it from time? Can we make it eternal or does it too have a life-span just as we do—as the Earth does? “Do you think art endures?” asks another character later on. Penelope answers, “I don’t know. Individual artworks, no. They require a lot of conservation. Art, with a capital A, I have no idea.”

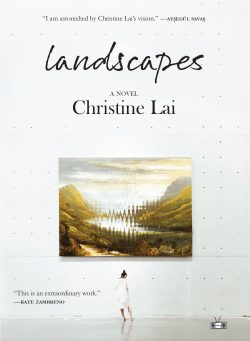

Reading Landscapes is truly an art lover’s dream—the novel is brimming with references to artworks both real and fictional. The challenge such ekphrastic writings face is rendering visuals into words, an often difficult and imprecise act of translation. But Landscapes succeeds because the art that informs its foundation is not only described, it is woven into the landscape of the novel itself.

“Mornington Hall was famed for its seamless transition between interior and exterior,” Penelope tells us. The same could be said for the book as a whole—Landscapes moves deftly across multiple other dichotomous divides. Penelope’s intimate diary entries (as meticulous and as closely observed as one would expect from an archivist) submerge the reader firmly into her interiority, but Lai’s richly drawn details of Mornington, awash in contradictions of opulence and atrophy—tattered trompe l’oeil wallpaper, flowers blooming in cracks on the walls—also ground us firmly in a setting outside the narrator’s mind; we understand Penelope more deeply because we can envision the world she writes from. Penelope herself is a passionate art lover, especially of the works of English Romantic painter J.M.W. Turner. Penelope’s love for art is so intense that it transcends her exterior world into her own interior. At times, the lines between the realms begin to blur. “At a certain point, I wanted to spend my life in that painting,” Penelope says of Turner’s Norham Castle, Sunrise, the first painting she fell in love with. She admires the way “the painting’s radiance belies its dark core…This is what I love in Turner—the way violence is embedded in a gleaming landscape.” This is true both of the landscape of Mornington Hall, with its fractured past and seemingly doomed future, and of Penelope’s own inner state, as an act of sexual violence from the past continues to invade and haunt her present.

As Penelope sits for a portrait by an artist friend, she finds her mind wandering more and more frequently into painful memories of her past. She attempts to stay present by mentally reciting “as a mantra” a Louise Bourgeois quote: “My memory is moth-eaten full of holes.” Penelope writes, “The more I recited, the more I resisted the images from the past that sought to latch on to me.” When she finally witnesses her completed portrait towards the end of the novel, Penelope thinks, “It was unmistakably me, but me as I exist in different times. Even though the image is static, it in fact records in its many layers the dynamic subject that dwells both past and present.”

What tense does art exist in? This is a question I found myself asking as I read Landscapes. Is art past, or is it present? Or is it more accurate to say that it contains both at once, moves through dimensions, just as we do? Is this what makes art human—maybe even mortal?

Another question I found myself pondering: is art a form of memory—or is memory a kind of art? Penelope recounts a conversation she once overheard on the London Tube in which two men debate the merits of painting from memory: “If you try to reconstruct something over the span of years, or if you try to reconstruct an event that happened a long time ago, how accurate can it be?” one asks. But Landscapes suggests that the reason why art moves us so deeply has little to do with allegiance to detail—maybe to love an artwork, to truly absorb it and let it pervade the exterior world to our own interiors, means that we make it our own, create something new in our minds. When a beloved Turner painting is stolen from Mornington (a commissioned reproduction of an original that was among those sold for repairs), Penelope mourns its loss before realizing “the Turnerian colors and the luminous core at the center of the darkness are lodged in my mind. These details have taken root in my imagination . . . so often that I find myself picturing A View on the Seine as if I had painted it.”

In her diary, Penelope remembers another incident in which she describes a beautiful view from the train that her partner sleeps through: “He said my description was as good as the view itself,” she writes. Something new formed, something beautiful persisting, in the wake of a loss—even if only in our minds: this, Landscapes tells us, is how art endures.