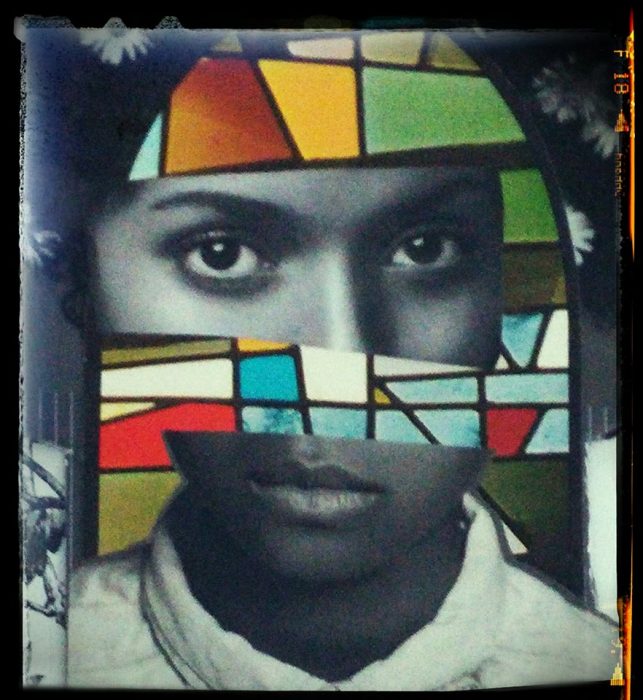

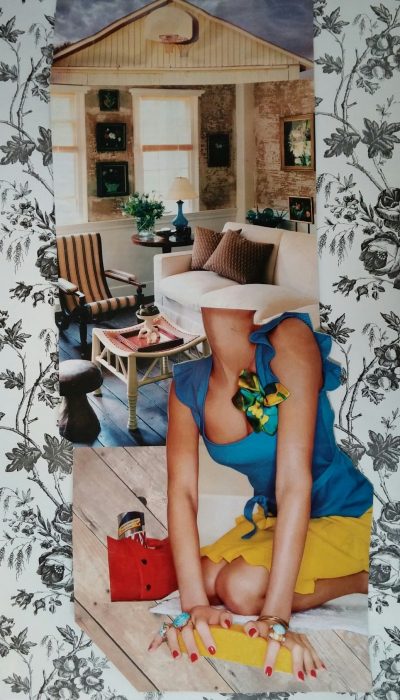

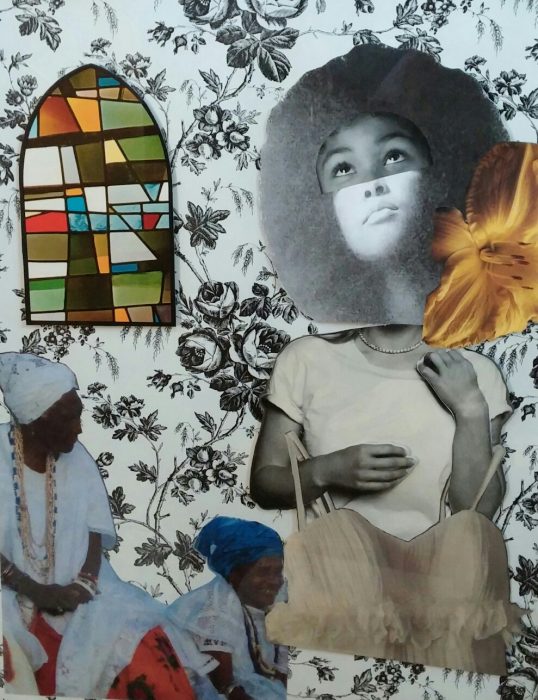

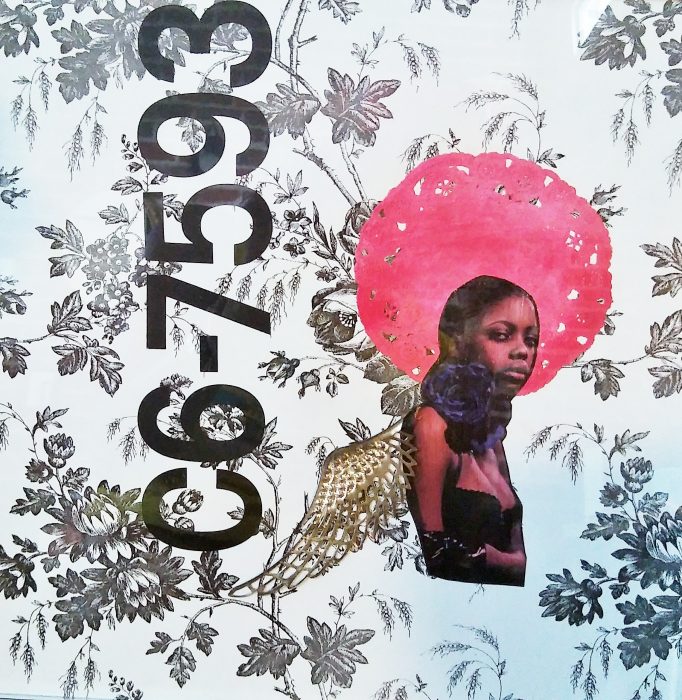

darlene anita scott’s collages are studies of the concept of the “good girl.” They explore the way these girls—especially “good girls” of color—manage and perform their identities. We were struck by the evocative complexity of these images and their rich surface textures, and we are thrilled to feature darlene’s work in Issue 41.4.

Art Editor Liz Blackford got in touch with darlene to ask her a few questions about this series.

Good Girl

Good Girl

Liz Blackford: You mentioned that this set of images is from a larger series called Tropism, named for the biological phenomenon in which organisms grow towards an external stimulus. I’m curious to hear more about the relation between this concept and the image of “the good girl” that you explore with this series.

darlene anita scott: First, I should say no one quite wants to be a “good girl!” (She’s not all that fun after all—always reading and thinking; often not into appearance and “girly things;” introverted and unable to relate, or be related to, by her peers socially or romantically for these reasons). But like any classification there is the danger of pigeon-holing. Pigeon-holed are girls of color when they are treated as a monolith whose characteristics—aggressive, loud, sexually realized—ignore the possibility that a good girl of color, or at least one with some of her qualities, can exist.

A girl deserves to be her full self and if elements of a good girl are elements of who she is, she needs to be allowed to be that. Allowed. Here is where the external stimuli inform her experience. History deputized into social constructs are the external stimuli that too often determine and define her existence. Social constructs become systemic, essentially organic in function, and so this phenomenon tropism seemed the most precise way to encapsulate this girl’s experience.

Fine

Fine

LB: Some of the images you shared with us appear to represent stages in the development of individual works. Could you talk to us a bit about your creative process?

DAS: I make a practice of collecting everything that I connect with. On whatever level. With words, that’s sometimes notes on envelopes, lines or words in my notebook, emails of bits of conversation to myself. With visual art, that can be a line drawing in my gradebook, ripped images from magazines, Instagram photos stored in a folder, pieces of broken jewelry. In these pieces, you see some of that process—the connecting part doesn’t always explain itself in the beginning; I just know that I connect with it and need to collect. Especially for these pieces, I think of the subjects as parts of myself that I was connecting to as I worked. But they weren’t always ready to open all the way up. So these pieces represent the evolution of our conversations.

Context

Context

LB: You mentioned that you primarily work in text, and these images were born of a poetry manuscript that explored similar issues and themes. Many of the artists whose work we highlight are also writers, and we’re always excited to hear how artists navigate working in multiple disciplines. What relationship does your work in the visual arts have to your writing?

DAS: I took a couple of years “off” from writing out of a personal frustration with my text. It was during that time that I turned to visual art and found it to be very useful to my creative development. I reacclimated to the organic nature of creating, enjoyed the practice of manipulating for precision, and became more attentive to the technical requirements of creating in that hiatus.

I see words, and even my less narrative poetry is heavy with imagery. So I came to the manuscript years later, somewhat because of some of the specific visual work I’d done during the hiatus. I envisioned the manuscript with photography. Like the writing hiatus I had taken before, I got frustrated with my text and started playing with my collection of ephemera and the project took this turn. I want to always honor my work with letting it be what it needs to be; I think the hiatus also taught me to do that.

June

June

LB: I’m curious about your use of mixed-media collage in this series. The figures in these images appear at once fragmented and carefully assembled, simultaneously emerging from and dissolving into the imagery that surrounds them. Do you typically work in collage, and/or was there any particular reason you felt that this medium might be well-suited to this project?

DAS: I like that—emerging from and dissolving into the imagery.

First, I began collaging as a frustrated college student who wanted a way to cover her cement walls. And because I was without materials or perceived technical skill (I’ve never had any formal training in art) to use anything other than what was at my disposal. I remember wanting to bring what I saw in my mind and what I recorded on paper to that space, partly as affirmation and partly as aspiration that I could look to every day. So I collaged a lot of posters from magazines.

There’s no question these motivations are in this collection. For instance, I tried sketching and was frustrated by my own lack of technical skill to execute the nuances of these girls’ experiences. I considered my collection of paints and canvases, fabric and ephemera, and tried a couple of other ways to “hear” them.

Their experiences are complicated—they engage and implicate the viewer’s gaze by choice and circumstance at the same time—as you called it: emerging from and dissolving into the imagery. And collaging allowed me to underscore that complication, to introduce some of the nuance I think.

Mae

Mae

LB: What inspires you?

DAS: What doesn’t?! Anything can inspire me in the sense that it may give me the urge to create and not necessarily in an ekphrastic way, like, trying to describe or even, in the explanation as given by Plato, to mimic the feeling of the thing, but rather to make meaning for myself of why I am attracted to that thing.

So I’m especially inspired by memories, how we shape them; of all the moments in a life, why them?

Photographer and artist Kwesi Abbensetts wrote “You may see the word pain./and it attracts you./Beware of it as memory.” But I am inspired by memories and why they decide to stick around, and I am seeking to find out why they—of all the objects, people, experiences, even pain—find a place in my brain and take a seat there. I take his instruction to beware as to be/aware and to actively engage that awareness.

Picture of A Girl Trying, 16

darlene anita scott is a poet and visual artist whose work examines the corporeal performance of trauma and the violence of silence—especially among women. Her poetry has appeared in Quiddity, J Journal: New Writing on Justice, and the Baltimore Review among others. scott lives and teaches in Richmond Virginia where she enjoys the humid summers, long runs, and homemade popcorn (not necessarily together).

“Bobbi” appeared in Hot Metal Bridge Issue 20 (201)

“Mae” appeared in Star 82 Review Issue 4.4 (December 2016)