It is an impossible task—to be safe in America when your neighbors are watching. It’s impossible to explain how your body is too large to protect, how history is also a place in the body. When I moved to the South, I became a danger. I made a disturbing sight flickering through the grocery aisles. I perpetuated uncertainty, and the townspeople, I affected them. At dinner with my partner’s family, only I hear the man asking that I pay attention to his body. And because I am listening, I am unreasonable, living with parallel facts: that I am American, that my citizenship is secondary to my neighbors’ perception.

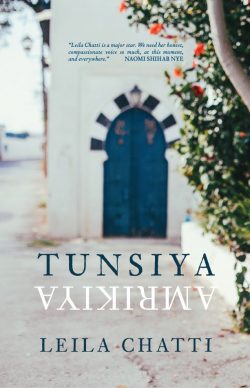

Leila Chatti attends to this duality in her first collection, Tunsiya/Amrikiya, a title that identifies the feminine within a nationality, and then the feminine within a second nationality. Leila Chatti is a dual citizen of Tunisia and the United States, and her poems explore her identity through a powerful, directing lyric “I.” Hers is a speaker who demands dialogue, which in its most basic form is the structure for acknowledgement.

It’s easy to imagine the speaker must feel defeated, pushed to the periphery. After all, “Jane and William had / so many apples, but never a friend named Khadija.” Who, then, will extend the generosity of apples to Khadija or to the speaker? But Chatti’s poetry constructs a center. Her poems are architectural in their narratives, with speakers who can be generous, who can receive bounty, even if the reader has not imagined these speakers lucky in their histories or their geography. If Chatti narrates a history she cannot control, she still hands her characters the knife. They are feeding themselves in poems like “Momon Eats an Apple in Summer”:

She keeps each sliver

to herself. Her fingers draw

the blade through the flesh

up to the bed of her thumb

and stop

and there is no blood—she knows

Chatti creates the abrupt line break, the isolating “and stop,” but Momon continues. The speaker narrates Momon past obstacles of prosody, and the sentence continues, which is to say, Momon will keep living. The speaker, in her record, sustains those she loves.

Those she cannot sustain with speech, she seeks to identify, to make their bodies sufficient. And perhaps this is the nature of a speaker in motion. If she cannot settle between two countries, the body, too, must be a place. For such a speaker, Chatti constructs the poem like a proof. In “Upon Realizing There Are Ghosts in the Water,” Chatti’s speaker confronts the defacing violence of political borders and risks her own body to give shape to an invisible death.

I should have known but the water

never told me. It sealed its blue lips

after swallowing you, it licked my ankles

like a dog. I won’t lie

and say the ocean begged for forgiveness;

it gleams unchanged in the sun.

Some things are so big they take and take

and remain exactly the same size.

The speaker is in conversation with the dead, an act that extends her humanity to her listener. “I waded in / to your grave as if trying it on,” and “when the waves came, / they gave me back.” There is the risk that the speaker could well be another body we “should have known,” after it’s lost in the Mediterranean between so many borders. Instead, she becomes a vessel for recognizing the grief that hasn’t been expressed and the lost figure who hasn’t been identified. If the ghost can be seen, it can be seen as part of her body, which “wore its salt like gemstones.” The poem extends the body, provides a whole ocean asked to house it, and a speaker also vast enough to wear the ocean, to carry the body of another, another’s endless possibilities.

It’s this certainty that surprises in Chatti’s poetry. Essential to her identity-proof is that someone will listen. Her speakers structure their bodies and their loved ones in cumulative optimism. Chatti’s poems are not naive. By extending the body (the refugee coffined by the Mediterranean Sea, the mother with “four hearts / outside her body”), Chatti describes vulnerability but also pinpoints violence; she creates opposing scales where the brown body is central, not the harm done to it.

When reading “Motherland,” its opening question, “What kind of world will we leave / for our mothers?” I return again and again to how Chatti’s “Okay When Are We Going” separates a mother and daughter remembering the aftermath of 9/11 while contemplating the consequences of a Trump presidency:

!200! !100!that summer after the towers sank

like a heart, she pinned the tiny striated flag to my breast

before my flight back there, the other land, as though it might protect me

from this one. My mother, looking the same

as she does now, white-lipped and terrified, in a Midwestern restaurant

Here is a mother struggling to disguise her child as herself. She disguises her child from her country by dressing her in the symbolism of her country. She is frightened, and her child is frightened: “I was a child. I cried. The flag shuddered on my chest.” Yet at the heart of this is a mother who will have her country recognize itself in her child. She’s willing to enact a string of signifiers so that every moment her child shakes, her country will have “shuddered.”

If we go back to the question, “What kind of world will we leave / for our mothers?” with the knowledge that the child is more vulnerable than the parent, that “the country she gave / me could kill me,” or that the mother risks her “four hearts / outside her body, buried / in brown and fragile skin,” then we are praying for the wellbeing of our country. We hope for the sake of our country that the vulnerable will survive—because in Chatti’s beautiful America, the loss of any brown child is unbearable.

Leila Chatti. Tunsiya/Amrikiya. Bull City Press. Published April 3, 2018. 37 pp. $11.70, paper.