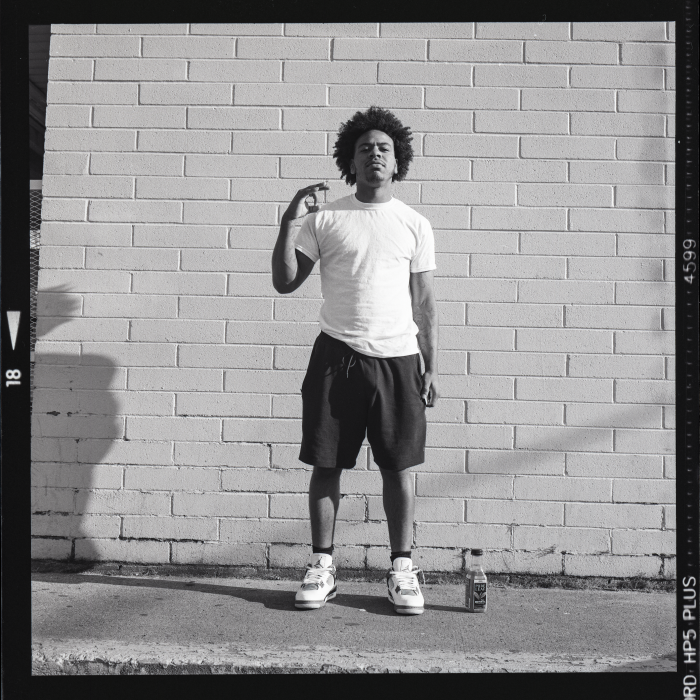

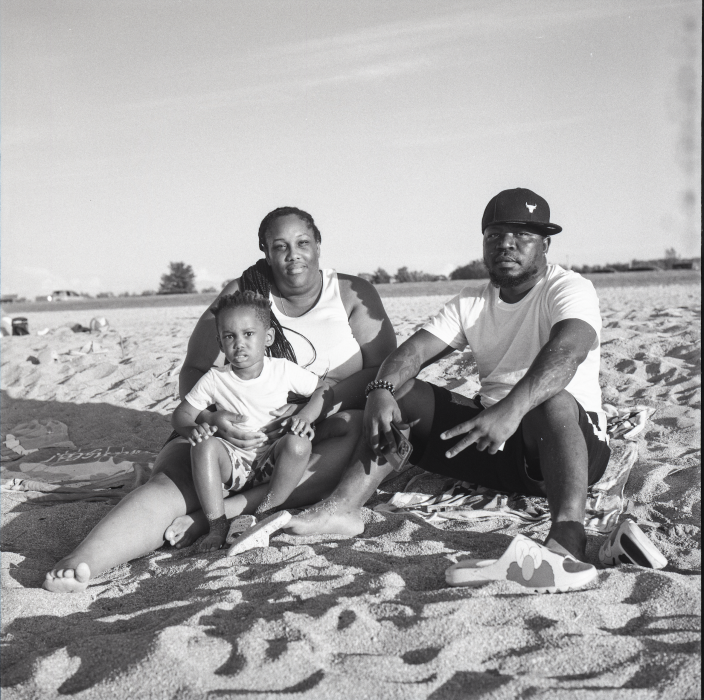

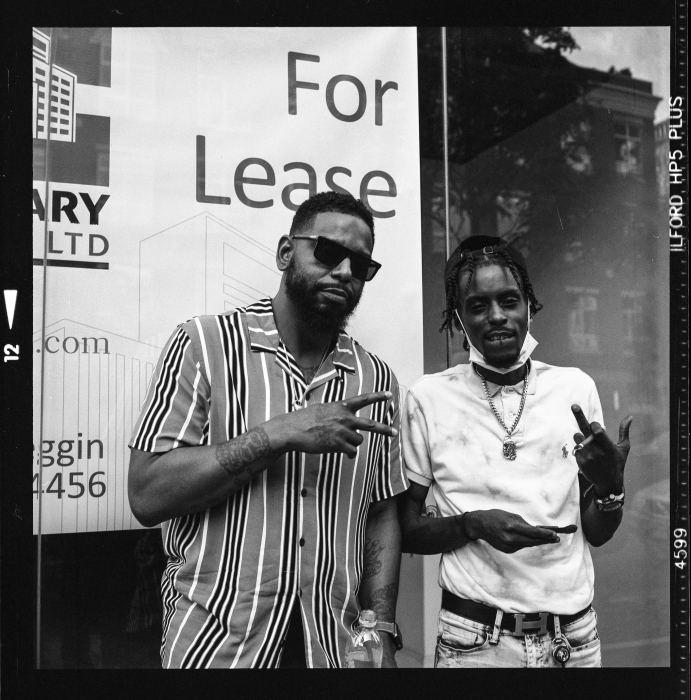

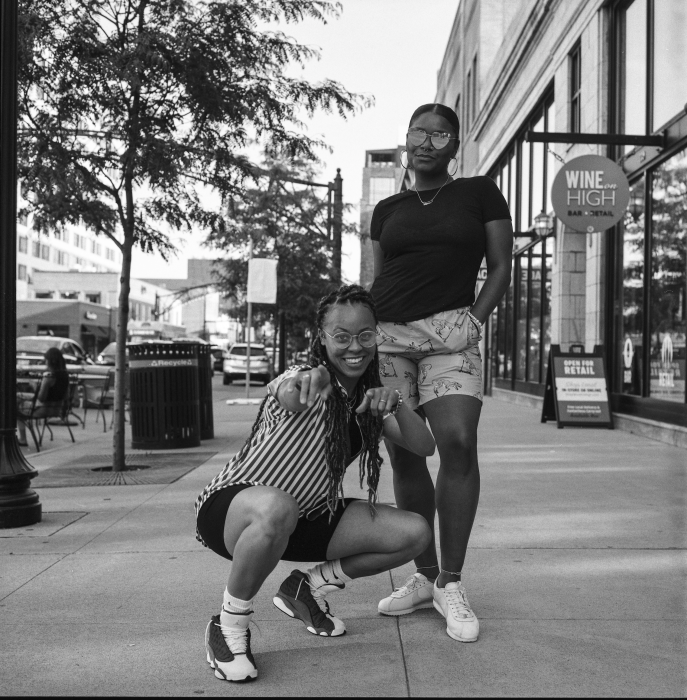

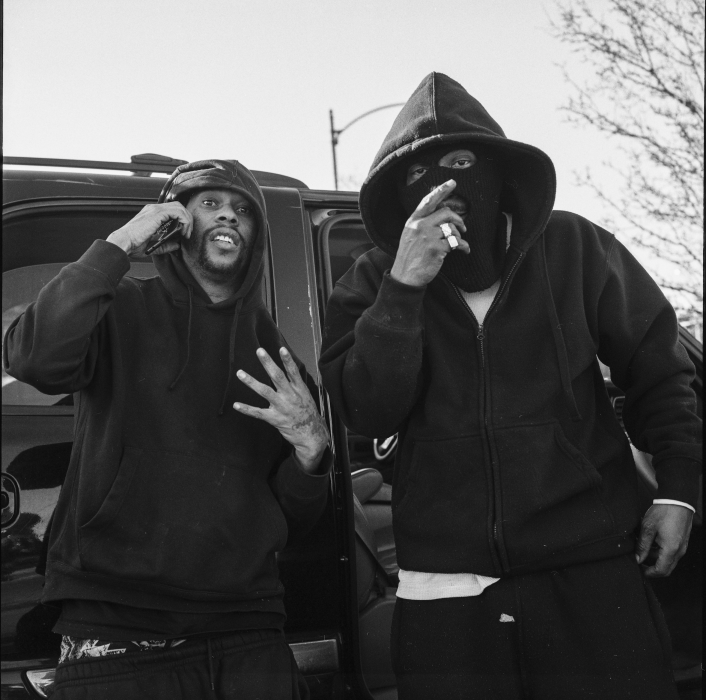

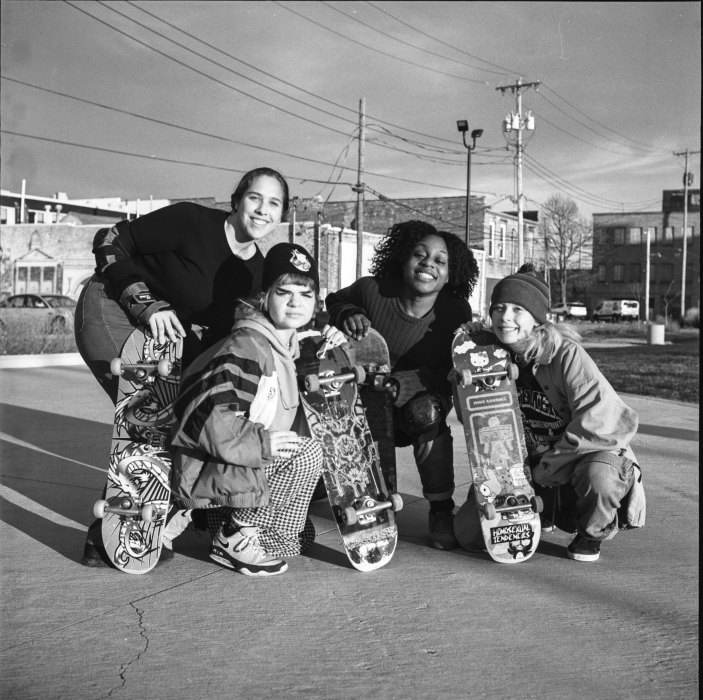

James Dickerson’s photography is alive. His black and white photographs vibrate with the emotion, energy, character, and story that comes with community portraiture. These expressive pictures offer glimpses so vivid, they evoke empathy and demand attention. Through Dickerson’s storytelling and listening skills, we glimpse into moments that will make you want to linger. Art Editor Arah Ko and Associate Art Editor Hannah Nahar asked Dickerson about the experience of taking these photographs.

Arah Ko: I was immediately drawn to how powerfully your photographs capture emotion and body language–from camaraderie to sorrow, joy, and resilience. I feel like I’m getting a vital glimpse into these people’s stories. What goes into the lead-up of taking your photographs? Can you tell us about your creative process?

James Dickerson: Energy. It’s all about energy and the life threads between us. I’m answering this question after bumping into an old friend on a walk. It’s been a solid 10 years since we’ve seen each other. He has his history and I have mine, but the smile between us was like ‘yo, what’s up!’ I want my photographs to solicit that warmth when observed. I actually struggle a lot with being seen. I’m in therapy now, but photography is a medicine for someone dealing with depression. Just being honest. I don’t make photographs for likes, but I do care for Black life and I am using my platform to support that desire.

AK: As a Toledo-based photographer, how does your relationship with landscape or location play into your work? Is there anything you wish more people knew about your hometown?

JD: Yeah, I’ve had some horrible experiences here. While I have the support of different orgs through my work and personal relationships, that doesn’t exclude me from some harsh realities. Those instances started to surface when I was a preteen and I can safely state that they’re why I go hard for my community. I wish I could wear the pride of Toledo the way others do, but they’re white and I’m Black. It’s not the same for everyone.

Besides that, I think knowing about people like Art Tatum, a legendary pianist, or author Austin Channing Brown, that they lived in the neighborhoods I lived in and make photographs in. Toledo isn’t terrible, it’s just a city doing city things.

AK: Your portraits are so vibrant, it makes me feel like the people are going to start moving any second! What is something you hope viewers take away from these insightful images and the people they represent?

JD: Haha, thank you. I wish I could see some of them again. I would love for someone to see my work and learn from it and challenge themselves to be empathetic to their own surroundings and the people. I get your discomfort, but take the risks that I take to know someone. Even if it’s minutes long in experience.

Hannah Nahar: Can you talk a bit about your relationship to grayscale monochrome photography, rather than color? Did you always work in this form, rather than color photography, and what drew you to it?

JD: I dabble in color, but not frequently. I home-develop everything to save some coins. I’ve considered color lately, but I’m no casual photographer and the cost would blow my budget. I admire people who can take 1-2 months to finish a roll of film. I think my fear of depressive episodes makes me more reactive. I photographed 4 people throughout today in different locations and also while driving. Idk. Black and white makes sense because I can print in my wet room. But it also compliments my need to steer your bias into a wall, right? Like I want you to think about the person you dismissed and recognize that and challenge yourself to do better. Color is cool, but not economically and not worth my time.

AK: Can you tell me about some of the challenges of your medium? Are there any photographs that were especially difficult or rewarding that come to mind?

JD: I have to walk for hours to make most of my photographs. It’s lonely and tiresome when neighborhoods are ghosts, or the people are distrustful of you. I want to make photographs in a trailer park, but I’m not ready. I met a white family before who didn’t understand the 2020 protesting. Said it didn’t need to expand beyond Minnesota. That was awkward because of my personal experiences. You have to decide what to do on the fly while these folks tear at your history and offer you a drink from their cup. I’ve missed some things that I should’ve made but you live and learn. There’s a book called Photographs Not Taken [edited by Will Steacy]. It’s about that picture you couldn’t make. It’s a solid read.

AK: I’d love to hear about some of your artistic influences. Are there any artists, icons, or muses that you draw from creatively? Where do you go for inspiration?

JD: Khalik Allah, Stanley Greene, Daniel Arnold, Mary Ellen Mark, Dawoud Bey. It kinda goes. I own almost 170 photography books. I’m self-taught and don’t have a degree in anything. I study from my collection and hang around Aperture.org or Magnum Photos.

AK: What is coming up next for you? Do you have any new projects or goals on the horizon that we can look out for?

JD: I should’ve prepared for this question but I’m poor about promotion. I just kinda work and work.

You can see more of James’ photography and projects on Instagram @dirtykics and at www.dirtykics.com.

James “dirtkics” Dickerson is a photographer who has documented Toledo, Ohio since the late 2010’s. His work emerges through the language of a neighborhood with a focus on Black and Brown communities alike.