Paige Quiñones’ “The Best Prey” is a bestiary of desire. Animals abound in Quiñones’ debut collection: spiders, foxes, whales, and sparrows, enacting primal wants and violence, relationships and intimacies. With her precise imagery and steady gaze, Quiñones makes of her animals a story of the body, of love, of mental health and gender, and family heritage.

From the start, we are ensnared in Quiñones’ web, like the bee caught in the spider’s web in the opening poem. “But imagine, pretend he is you: / beauty is the cold bind.” Quiñones does not mince words. The reader has come here looking, perhaps, for beauty, and beauty is abundant in Quiñones’ poetry, but no line is innocent or simple. Even as we admire the vividness of Quiñones’ language Quiñones turns her gaze, and we become prey. “I am complicit,” Quiñones ends the poem, complicit in the act of writing, in desire, in the hunt. Thus, Quiñones establishes the drama of the whole collection, the sway from predator to prey, object to subject, writer to written thing. All the while implicating the reader, as voyeur, or as some more active player in the game of predation and desire that Quiñones lays out.

Quiñones is an adept tour guide through this jungle. We soon return to a spider in the poem “Luna de Miel,” living, dying, and consuming its children in a goblet of water between two lovers. In “Love Poem: Fox,” Quiñones plays with the imagery of the hunt: a rich man on a horse, his gloves and hunting dogs. “To dress myself in woman / would be a finer sport,” Quiñones writes. The speaker becomes fox, becomes woman, measuring its predator and the chances of its survival. It’s a radical and frightening kind of love poem, and in seven short couplets Quiñones flips the familiar form.

The speaker is never only prey. Again and again, Quiñones refuses a singular narrative, or a single form. In the prose poem “That Which I consider Untamable,” Quiñones conjures something like a fairy tale. An animal leaves dead birds at the speaker’s doorstep, the birds “splayed open like a / gentleman’s waiting hand.” Here is death, the gifts of courtship. The speaker catches a fistful of the animal’s fur and Quiñones writes, “it is not / enough. I would like his entire pelt. I would like to lie in it.” The voice claims agency and power, even if it is a complicated power. Love and violence are always intertwined, and the poem asks: can there be want without consumption? Love without ownership?

There are human animals, too, family histories across language and time. In “Dueña del Bosque,” Quiñones writes, “You think you can return to that place / where your feral tía / climbed down from the mountain.” Natural imagery and the familiar are linked through language, and Quiñones explores the impossibility of return and gendered intergenerational trauma. In “La Operación,” the speaker imagines the voice of her abuela in Spanish Harlem: “duerme duerme duerme,” says the grandmother. With long lines and single-sentence stanzas, Quiñones conjures a vision of family origins, and the violence of men and medicine against women’s bodies.

And there is longing, as in the poem “Alternate Realities.” Each line begins with the conditional “if,” and with each “if” Quiñones conjures a question about love, health, and home, about what might life look like if something were different. Quiñones offers no answers; the reader must imagine what these other timelines might look like. Placed in the third and final section of the book, the poem draws on everything before to fill in the blanks. Quiñones employs the magic of what’s not there, what’s absent from the page, to fully activate the reader’s participation in the poem.

In some ways, the collection is a darkly honest choose-your-own adventure of love and its counterparts. Roleplay is encouraged. In the final lines of the final poem, Quiñones’ writes, “You are the quetzal I’ve snared / & I’ve stolen a feather & / you expect to be released.” We are haunted by the expectation of release, and the floating ampersands that bookend her line, like twisting snakes. “Maybe our roles are reversed,” Quiñones ends the poem. Start over, Quiñones seems to invite, read the collection again and play all the roles, the messy but alive human and nonhuman animals that populate this landscape of desire. More than simple metaphor or archetype, there are real bodies in Quiñones’ lines, bursting with pain and passion.

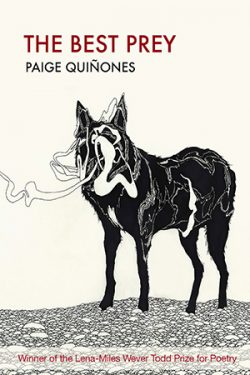

“The Best Prey” won the Lena-Miles Wever Todd Prize for Poetry from Pleiades Press. Paige Quiñones earned her MFA from the Ohio State University and is currently a PhD student in poetry at the University of Houston.