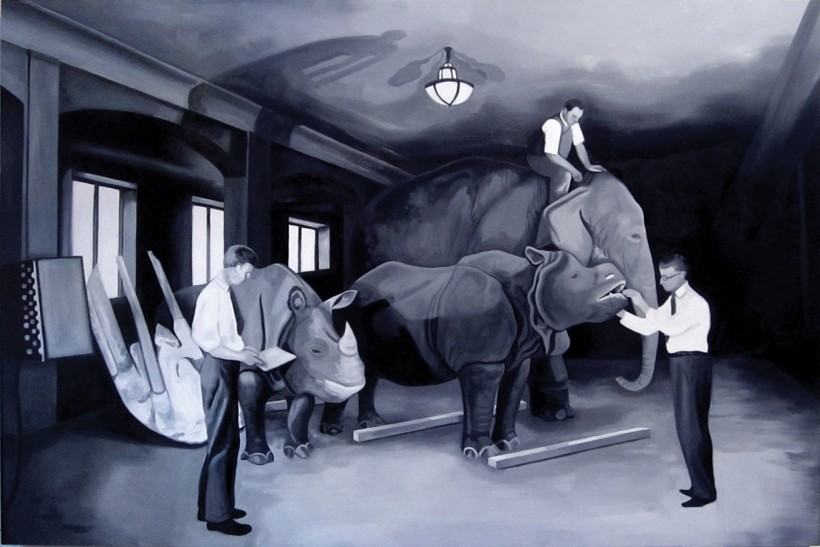

Each painting in Lina Tharsing’s series Making a New Forest portrays a lineage of documentation handed down to a new artist. Using archived material from the American Museum of Natural History, Lina paints from black and white photographs that document the conception and composition of ecological dioramas constructed in the 1930s. As paintings, the lines between the creators and created environments blur, and the human figures seem to melt surreally into the ecology they are fabricating. Lina spoke with Associate Art Editor Janelle DolRayne about translating photographs into paintings, the binary realities of nature, and how a museum diorama acts as a surrogate for natural environments.

JDR: In this series of paintings the viewer witnesses moments of imagination and creation in the building of the dioramas. Can you tell us of a particularly memorable moment of imagination during the process of painting or conceptualizing these pieces?

LT: This series is based on archived images from the American Museum of Natural History. I happened to stumble upon black and white photographs that documented the building of the dioramas I had been painting for two years. The moment I saw the pictures, I knew I had to paint them. I was already thinking about how to reintroduce the figure in my work, and about how these figures might interact with the dioramas. The first image I rendered was Making A New Forest; as I painted it, I increased the contrast and emphasized a spotlight in the center of the painting, which became the method by which I treated all the others. It’s hard to describe the feeling of creating that first painting, it felt like magic. The figures were on an ambiguous stage set, the magic and mystery of the diorama came to life, the trees seemed to glitter, and the figures’ white shirts glowed. The photographs were already a fascinating record of the diorama’s history, but as paintings, the images were freed from documentation, and took on deeper symbolism.

JDR: That’s so fascinating because there are two levels of recreation happening that both yield a deeper symbolism, the people making the forest and the artist (you) recreating the photograph. Did you feel like you could relate to the figures in the photos/paintings as a creator?

LT: I think all artists are delighted and amazed by the ability to create, to be able to paint an image into existence. What’s interesting is the more a painting comes to life, the more it begins to take on a life of its own. And these paintings are large enough, four feet by six feet, that it’s easy to feel like you are inside the diorama when you stand close enough to the surface to paint it. The great thing about using a figure in a painting is that it allows not just the painter, but the viewer something to identify with.

JDR: The paintings ask the viewer to think about humans’ relationships with the natural world and the desire to understand it. Is there anything about your own relationship with nature and your environment that informs your work?

LT: I believe that multiple realities can exist simultaneously and that something can be both real and artificial at the same time. Sometimes nature can feel wild, and yet completely composed. The natural history museum dioramas are a surrogate for natural environments. We can go to one building and travel across continents, visit various ecosystems, and observe wildlife in extreme detail. There is something eerie in the still silence of the diorama; real creatures are not so quiet, and yet these animals are real, and the environments are exact. I am more interested in the tension of those multiple truths, but the paintings could also be seen as a commentary on our dwindling ecosystem and the need to preserve it in whatever capacity we can.

JDR: It’s a bittersweet thought to see these dioramas as surrogates: sweet because they are standing in for a specific and necessary place, and bitter to think that place needs a surrogate BECAUSE of the threat to its existence. Can you tell us a little more about how you see the paintings as a commentary on our dwindling ecosystem?

LT: As you mentioned, these dioramas are not just educational tools, they are also surrogates for specific places across the globe. At the time they were created, they employed the most cutting edge technology to create a virtual reality. If these ecosystems disappear, that virtual reality will no longer be a simulation of a place, but the most real example of that place.

JDR: You are such a brilliant colorist, why did you decide to do these paintings in black and white?

LT: This series is based on archived images from the American Museum of Natural History. The photographs are black and white, shot in the 1930s. Initially, I painted various versions in color. I made a few small watercolors, and tried to make one large version of the buffalo diorama with an imagined color palette, but none of them really worked. Eventually, I decided to experiment with painting them as they appeared and became fascinated by the process of transcribing a black and white photograph into a black and white painting.

JDR: What I first admired about the paintings was how they toed the line of surrealism very smartly, and I think the choice to paint in black and white further blurs the line between real and artificial. There are moments where we are not sure if the curators are part of the ecosystem or if they are creating it (i.e. Condor Group). Was this the case in the photographs, or did the images approach the surreal as you painted them?

LT: The photographs themselves are already strange, but because they are silver gelatin prints from the 1930s of a specific place, the viewer knows what they are looking at. Once the photograph is translated into a painting, the line between what is real and what is artificial becomes blurred. Photography still feels like its documenting an actual scenario, whereas painting feels symbolic, no matter how realistic it is. The artist’s hand is always present. At a glance the landscape within the diorama might feel like a believable place, but then the harsh shadow the figure casts upon it will make it suddenly feel flat. There is a push and pull between 2D and 3D. There is also a tenderness between the scientists and the animals. The men in lab coats are caring for the environment they are creating as much as they are building it.