I think we learn to be worldly from grappling with, rather than generalizing from, the ordinary. I am a creature of the mud, not the sky. — Donna Haraway, When Species Meet

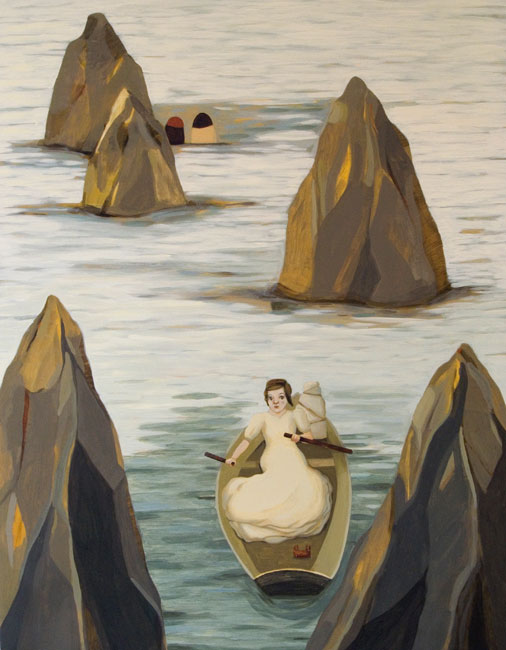

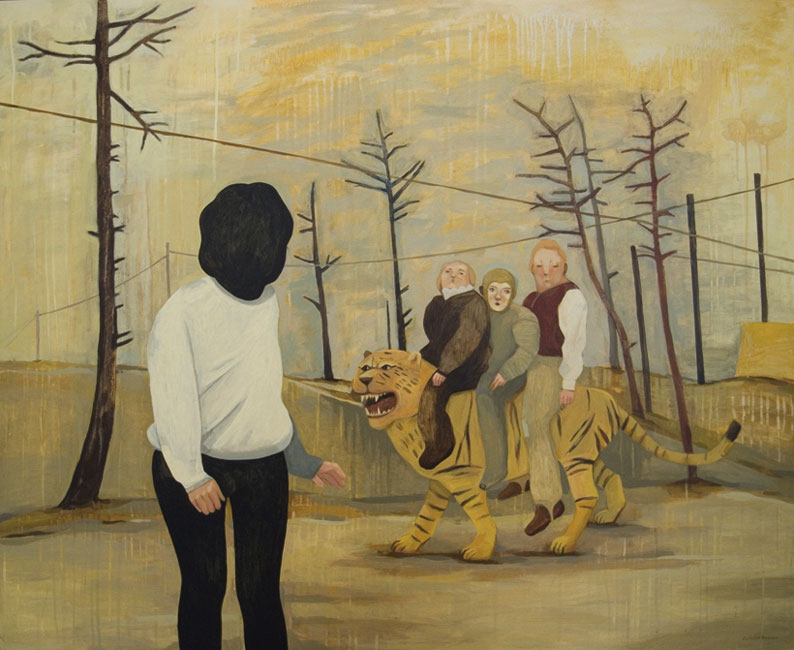

The creatures in Camilla Engman’s paintings are certainly more mud than sky. What is fantastical in these images is not so much that their figures are extraordinary but that they relate to each other in extraordinary ways. The woman on the golf course who holds a pair of goggles; the man with dog ears and boxing gloves; the boats that have found their way into the woods: these conglomerations ask to be sorted out and made sense of; they ask for stories to be told and for the fairy tales hiding under their surfaces to come out of hiding. But Engman’s figures also resist this dissection, clinging at every moment to their other half: the woman to her goggles, the man to the part of himself that is dog, the boats to their trees.

Donna Haraway says of the hybrid creatures that fill her critical work, “In every case, the figures are at the same time creatures of imagined possibility and creatures of fierce and ordinary reality; the dimensions tangle and require response.” This description—intended for laboratory mice that have been given cancers and cages as companions; humans who have opened their bodies to machines; and the companion animals that live beside us—is aptly applied to Engman’s images as well. Each not-right and just-off figure arrives without a history and yet persistently present, demanding to be considered but not broken apart.

Of her hybrids, Engman writes:

The “animal people” have always been there. I do not think of them as animals or humans. For me that is not important. I think of them as people. It may be that the animal people are the most human ones … people with animal instincts. Trying to explain the world in my paintings makes me realize that there are almost always two sides to it all. Like the dresses: they are protecting and comforting, but at the same time they make the wearer clumsy, slow and trapped. Lately boats have emerged, preferably on land. For me a boat is adventure, freedom and a safe place—at the same time you are trapped, you have nowhere to go and you are in the hand of the one that is steering the boat.

Haraway describes this push and pull as a “cat’s cradle game in which those who are to be in the world are constituted in intra- and interaction. The partners do not precede the meeting; species of all kinds, living and not, are consequent on a subject- and object-shaping dance of encounters.”

In Engman’s Smokers in the Neighborhood, a figure sits on a rock, covered to the knees by what might be a sweater. But this relationship is extremely unstable: is the garment a parasite, taking its form from the body beneath it, or is the body drawing protection from this covering? Should agency fall with the human body that sits, unmoving, on the rock or with the sweater that seems—like fungus overtaking a corpse or kudzu claiming an abandoned building for the forest—to be possessed of an alien intelligence?

Engman’s paintings require that viewers consider how to exist among all the strange relations that bind the mud creatures of this world to each other. How to imagine ways that ordinary objects might come together without obliterating one another. How to be both safe and clumsy.