Justin Runge lives in Lawrence, Kansas, where he serves as poetry editor of Parcel and helms Blue Hour Press. He is the author of Plainsight, published by New Michigan Press. Poems of his have appeared in Linebreak, DIAGRAM, Harpur Palate, and elsewhere. He can be found at www.justinrunge.me. Justin’s poems—“The Arbor” and “Love” —appeared in Issue 36.4 of The Journal, and he recently spoke with Poetry Editor Michael Marberry about these poems, the connections between poetry and film, and the role that technology might play in literary publishing.

Michael Marberry: “The Arbor” and “Love” are such weird, wonderful things—enigmatically titled, very carefully constructed at the line-level, and beautifully haunting in their imagery. I’m curious: where in the world did these poems come from? What inspired or shaped them? I must know the answers to these questions immediately!

Justin Runge: Well, the real “secret” behind the project is that each poem is a response to a trailer for a movie I haven’t seen. The project is inspired by Rae Armantrout’s Versed, which has a poem—I think it’s called “Versions”—with sections titled after a film. She doesn’t draw attention to their true natures, but I remember thinking, “Huh, The Happening? Like that M. Night Shyamalan movie?” The application of ekphrasis to trailers was very intriguing to me. I was in a slump, so I thought that using trailers as prompts would get me writing. Like Armantrout, my poems share titles with their respective films: “Love” and “The Arbor.” (The trailers can be found here and here.)

MM: Wow! I never would’ve guessed that these poems spawned from movie trailers. In fact, hearing you talk about these poems, it seems like form was the major catalyst for their creation. That’s very interesting.

JR: Form fascinates me, and trailers are a definite form. With a little distance from their advertising function, they become almost experimental short-films—clipped narratives with overt re-sequencing and a primacy placed on the compelling image. But their form has become rigid: similar run-times, similar beats, similar musical cues. I wanted to mimic that stricture by using the same “fast-cut” line length, the same number of lines, and even the same number of stanza breaks.

I’m also fascinated by the strange relationship that trailers have to narrative. They’re promoting something distinctly narrative, yet they interpret that narrative, twist it, condense it, and leave it incomplete. A trailer’s true narrative becomes something “above” the trailer, emotion-driven. An audience’s emotional response to any trailer would graph pretty cleanly to Freytag’s triangle, I think.

MM: So, you chose films with which you were unfamiliar. Then what? Take us through your process a little more and what you discovered.

JR: It was important for me to draw the images out as purely as possible, so, as I said, only trailers for films I hadn’t seen made the cut. No ties or affinities junking things up. Films with minimal titles—one word, with/without an article—so readers would arrive without preconceptions. “Some Like It Hot” or “There Will Be Blood” were out of the question.

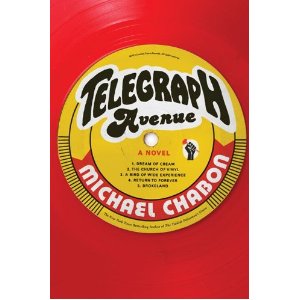

I’d watch the trailers only once and pull everything from memory. I was curious to see just how resonant the images would be, how they would concretize. This also kept me from doing too much scavenging for “good stuff” or prewriting. What hit me hardest? What seemed strangest or most capacious with meaning? Taking those images, converting them to language, unpacking them—that was the fun of it.

Returning to the poems and the trailers now, I’m surprised how little they sync up. At the time, I felt they were almost documentary, but they’re much less slavish than I had thought. I color out of the lines, and that’s a good thing.

MM: I’m very intrigued by the possible intersections between poetry and film, as they seem like two forms of expression uniquely capable of rendering traditional narrative, high lyricism, and formal experimentation. (I’m thinking, in particular, of folks like John Ashbery, Maya Deren, Lisa Jarnot, Andy Warhol, etc., who clearly saw some connection between these forms.) If “The Arbor” and “Love” are inspired by films that you haven’t seen, let’s talk about things that you have seen or experienced. Are there any filmmakers whose works strike you as particularly “poetic” in some regard? Or, conversely, are there any poets whose works strike you as being “cinematic”?

JR: You nailed the elements that film and poetry share. An even more distressing characteristic: they’ve become definitions of other genres, other categories. It’s more of a problem for poetry. People love to call other media “poetic,” but they’d rather not engage with actual poetry. The adjective (“poetic”) is almost pejorative. Whereas “cinematic” designates cool, vastness in scope, and contemporariness, “poetic” indicates dowdiness, pretension, and impenetrability. We’ve lost their critical applications. They’ve become value definitions, useless.

Jeez! Now that I’ve complicated the question, I’ll answer it. David Lynch is a poetic filmmaker— disjunctive, dreamlike, referential. He also avoids language in his work, which actually makes his work more poetic. The late Chris Marker, Murnau, Tarkovsky, Dreyer, Ozu—they succeed because they’re using the language of film and not actual language. Moments of Michael Haneke’s The White Ribbon and Wim Wenders’s Wings of Desire stay with me like lines and stanzas. The obvious reigning cinematic-poet is Terrence Malick, though I’m worried his flood of new work will sour people to his brand of mystic sentimentality. Lars von Trier’s latest films extend toward poetry (maybe bad poetry?), but he’s too much a filmmaker to allow an entire movie to live in a poetic space.

Cinematic poets…that’s harder. My two pieces don’t build that bridge—they’re poems, through and through. It’s actually difficult to think of examples because there’s the lazy definition of “cinematic” to avoid: one that involves kineticism, heavy plotting, ostentatious transition. That describes my poetry when I was younger, when I was riffing off other art-forms as I found my legs. Maybe it’s easier to think of the cinema of Eisenstein and Griffith—spatial relation, montage, juxtaposition—in the attempt to find cinematic poets. Strand, Simic, and Stafford come to mind; their use of body placement and setting feels filmic. The tension and cross-cutting of Forché’s “The Colonel.” This feels like uncharted territory, Michael! There’s a literature thesis in there somewhere!

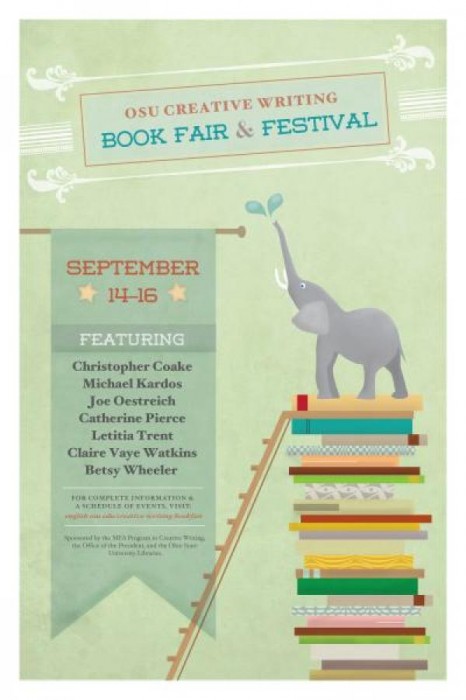

MM: Ha! Yes, I think there might actually be a book in there. It’s certainly very interesting to think about, at the very least. OK…last question: I’m a big believer in the aural power of poetry, so it’s such a delight to hear you read your poems in our recent issue. We’ve only recently begun to offer this audio dimension to our readers with the introduction of our website and our online issues. I know that you’re a pretty savvy tech-nerd and have been involved with some online publishing—most notably the gorgeous web-chapbooks at Blue Hour Press. What sort of role do you see technology playing in literary publishing? What are some of the benefits and/or dangers of the literary community’s shift toward more and more online production and distribution? Where would you like to see all of us head, as a community of writers and readers, in this regard?

JR: I don’t think technology is just playing a role these days—it’s the stage (or, at least, one of them) and it’s gaining square footage. The sooner people step onto this stage, the sooner we can gather people into its auditorium.

The major risk, I think, is that people see the object, the work, the effort in a digital space as being less physical. There’s a weightlessness to digital publishing. Today’s reader can sort of cloud-hop to this Dickens novel, this long-form essay, this poetry blog—constantly consuming half of the work, a quarter of the work, and bouncing on. It’s like a glorious buffet where you can take a bite of this, a few grapes, a sip. There’s less pressure to sit down to dinner.

I’ve always said that online publishing needs to gain a little gravity. Publishers need to make the experience feel as lavish and tactile as print, but generous in ways that only the web can provide. Lots of print books come with “bonus content” in the back, which I think is silly. The web can do that effortlessly. The Journal can put audio of the author right next to the work, publish an interview with her a few months later, connect the work to related content that requires just a click. But it has to be beautiful; the reader has to want to dwell in these spaces. A book will always feel comfortable in this way. That’ll ensure its continued existence. How do we begin to curl up with the web?