Uncategorized

Larissa Szporluk is the author of five books of poetry—most recently Traffic with Macbeth (2011). An associate professor of English and Creative Writing at Bowling Green State University, Szporluk has received grants from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. Her poem “Startle Pattern” appeared in the Spring issue (37.2) of The Journal. Recently, Szporluk spoke with Associate Art Editor Janelle DolRayne regarding the origins of “Startle Pattern,” the roles that narrative and image play within her poetry, and both the unique challenges and opportunities that depression can provide in the landscape of an author’s work.

Janelle DolRayne: I’m glad we get to talk about “Startle Pattern” since it encompasses so much of what I admire about your work. The poem starts at a place of renewal/birth and conceptualizes and mythologizes from that place. Where did this poem begin for you?

Larissa Szporluk: “Startle Pattern” was inspired by a fascinating criminal studies book called Eraser Killers that covers some of the most famous cases of homicides committed by, well, mostly husbands who wanted to “start over” and, being demented and cruel, preferred murder to divorce. Eraser-killing involves making the person disappear completely, which I suppose is part of the “fun.” The Peterson case was so haunting that I still can’t shake it. “Startle Pattern” is just a poetic retelling of the pivotal moment—the case began to unfold once Laci’s fetus washed up on shore. She was nine months pregnant when killed and the fetus did, in fact, emerge from the uterus posthumously. It’s an image beyond myth, beyond all that we’ve read and been told.

JDR: It is an extremely unsettling image. In your eyes, how does the image surpass myth?

LS: I suppose the image surpasses myth by the fact of being real. And, being real, the image has no agenda other than to have happened. There is no comfort, no message, no “purpose” to a dead fetus rising out of an isolated uterus at the bottom of the sea, and yet, because we are instructed by tales of resurrection—the phoenix, Christ, etc.—we want so badly for reality to be positive. We want the miracle of the little boy surfacing alive. We want him to stand trial against his father. We want the triumph, and we’re never going to get it. Perhaps that unrequited yearning for the impossible contributes to the image’s power as well. It’s a distorted renewal/birth but ultimately sad and empty. The distortion isn’t thrilling or instructive. It just is.

JDR: Your poems are extremely intimate. As a reader, I always feel positioned within the mind and body of the poem, never on the periphery. They have an extremely strong internal motion, even when you are writing about and/or through a character. How do you see the relationship and positioning between speaker and reader in your poems?

LS: Once upon a time, I would have said that there is no relationship, that speaker and reader are more or less merged in my mind when I’m writing. I used to write for a reader who was essentially an aspect of the speaker. Now it’s more complicated. After finishing a very difficult prose project, one that involved a total separation of reader and speaker, I doubt I’ll be able to get that unification back. My sense of the reader now is as a cold, faraway planet that I must somehow try to entice. The strong internal motion that you mention depends on the reader being in the know, being attached, even being dragged in some cases. It’s an aggressive stance, I would say, and, yes, intimate too but not always consensual.

JDR: Do you mind talking a little about the prose poem project and your plans for it? Specifically, why did it call for a total separation of reader and speaker?

LS: It’s funny that you say “prose poem project” because that’s what I’m on the verge of writing now. The project I referred to earlier was a prose fiction project (I hesitate to say “novel”) that has been a disaster, of which I’ll spare you the details and head straight to the question.

Trying to write popular fiction (attending to plot, character, pacing, etc.) is such an intricate, mechanical process that there is no room for indulgence. I found myself basking in narrative details that were of no importance whatsoever—in retrospect, they were grotesque in their gratuitousness. Upon learning that all my efforts had no value, well, you can imagine. Ouch. It was a slap to the soul. Poetry, mine anyway, has always lived in that indulgence; my prose dies in it.

I signed up for the Tupelo 30/30 that begins June 1st and involves writing a new poem every day for that month. I plan to apply this separation strategy to short prose poems. My imagined reader, as separate as they come, is a cold-blooded, poetry-hating grouch.

JDR: In your work, you recreate myth by responding to mythology such as The Adventures of Pinocchio, the biblical Fall, and Macbeth. How responsible do you feel to the original myth when recreating it? How do you see the relationship between old and new mythology in your work?

LS: The Pinocchio poems tried to stay true to the original story and aimed merely to accentuate the images that I found to be most poignant. I would never try that again. It was discouraging because only too late in the project did I realize that I was being a pest and, by then, I had already spent a couple years on the poems and was under pressure to publish a book to get tenure, etc., so there really was no turning back.

I’m not ashamed of the poems but of the impulse. There was no need for that story to be picked at; the poignancy is blatant. But I did come away with a lesson: image is empty without narrative. It’s the difference in power between a blue goat and the blue goat. Which is more interesting?

JDR: At first, I had my mind made up about my answer: the blue goat. But then I thought that a blue goat indicates that the speaker is creating a world in which blue goats are common, which excites me. But I suppose that is an argument for creating narratives within images as well, so I’m going to stick with my first answer: the blue goat.

But thanks for sharing that lesson with us. I’m curious: how has your relationship with image-driven poetry changed since learning this lesson? Both the reading and writing of poetry? Does it still have a place for you?

LS: I’m a lot less patient now. I’m more frightened. I wish it were the opposite, that aging had made me more patient and secure. Unfortunately, it didn’t go that way. I’m paranoid about superficiality, and if an image doesn’t grind or pierce immediately, I dismiss it. As mentioned above, I understand the role of narrative more, so I work to inject the weight of story into nearly every image—key word: “work.” Writing imagistic poetry has become more difficult, more laborious, because “story” has to be created before the language work can begin.

Also, because of the fear. It’s like I know there’s a deeper poem in any given gathering of words, and I’m afraid of not getting there because the only access to it is through abuse—beating and squeezing those words until they actually mean something. Now, of course, that’s perverse, but that’s how it’s been.

Even “Startle Pattern,” which was working from a true story and therefore required little imagination on my part, had to be reconfigured a thousand times, and I’m still not pleased. The ending is a little too gentle. I didn’t get “under” the comber. He’s just a prop.

JDR: From what I understand, you split your time between northern Ohio and northern Italy. There are traces of Italy in The Wind, Master Cherry, The Wind and of Ohio in Traffic with Macbeth. How do these two places enter into your work and process?

LS: I haven’t really begun to explore the impact of northern Italy yet. The Italian influence in Master Cherry was connected to Lombardy, where my husband’s family is from and which is uncannily like northwest Ohio. When they moved to Domodossola in 2006 (a small city in the Lepontine alps), my first thought was: I want to die here. Maybe that’s just middle-age sentiment, but it’s also a beautiful feeling to go running around feeling so happy that you want to die.

I don’t feel that way in Ohio. They’re geographic opposites. Here (I’m in Domodossola right now), there is no horizon. Everything is vertical. The only way out is up. Whereas in northwest Ohio, you’re hard-pressed to find a bump. Everywhere you go, it all comes with you, and it never ends. I like the two extremes. They’re emotional platforms.

I tell students who are depressed or having the “block” that depression has its own music. They should write no matter what and not think they have to be “high” to write good poems. Philip Larkin’s “High Windows” comes from a deep, flat place. He’s brooding and the brooding gives way to a kind of mental chutes-and-ladders. Depressed, he has to create all those altitudes in order to move the poem along. When the poet is already “up,” the poem can be restricted by a reluctance to descend. There is something courageous about flatness, strange as it sounds.

JDR: Not strange at all! I moved to Ohio after growing up in the Rockies and spending time in California, so this really resonates. I think the difficult part is to find a way to begin out of flatness. You can’t rely on gravity to take you somewhere. How do you manage to ignore the difficulties of flatness and to build altitudes in your poems out of flatness?

LS: But you can rely on gravity—you can keep going down. That’s the only benefit of depression—you’re closer to the depths. I’m not talking about mystical meditation-induced depths. I’m talking about mentally disturbed ones. That’s where the energy is to build the altitudes you’re talking about; put simply, you scare yourself out of the flatness!

OK, now it’s getting convoluted. I’ll start over: You’re in the flatness. Your mind is flat. You’re precisely numb with your own ennui. It’s only in that state that you feel the pull from below, a kind of Swedenborgian lower spirit telling you that you’re nothing, you’re a loser, you’re hopeless. So you agree. And when you agree, you’re pulled even further into a whirlpool of suicidal whisperings and bad feelings. And then—there it is—you either do yourself in or you become a hero.

Of course, we’re talking about writing a poem, right? So what is your “weapon?” Words, of course, and suddenly the words come to your rescue, and they’re loaded with God or whatever feels almighty to you, and they’re strong because, no, you’re not going to surrender to the lower spirits. It’s too easy to just crumble and self-annihilate, too easy and stupid, so the energy starts building, the will to live returns, and the rhythms start climbing and pulling you up and up. Pretty soon, you’re not only out of hell but beyond the flatness and getting so high now that not even the words can keep up and, as in the Larkin poem, the image steps in, the deep image that represents the narrative you’ve just been through—high windows—salvation of the highest kind, relief in endlessness, the summit.

Unfortunately, this psychodrama is both necessary for the poem and exhausting for the poet. I no longer believe that the altitudes live in the words alone. The psychotic spirit (or the lucky, healthy one) has to tryst first with itself and then with the language in order to make everything rise.

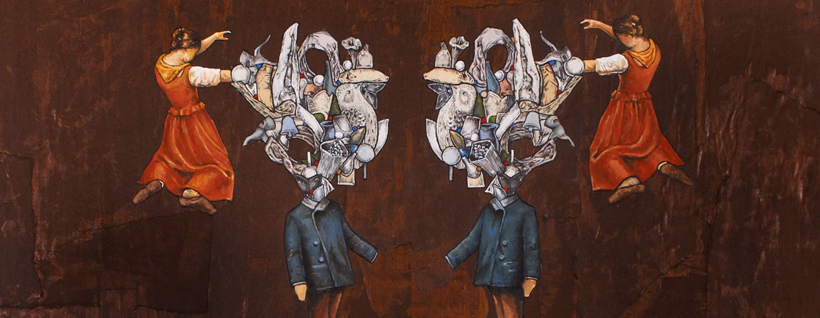

Breath. See more work by Jason Borders.

Breath. See more work by Jason Borders.

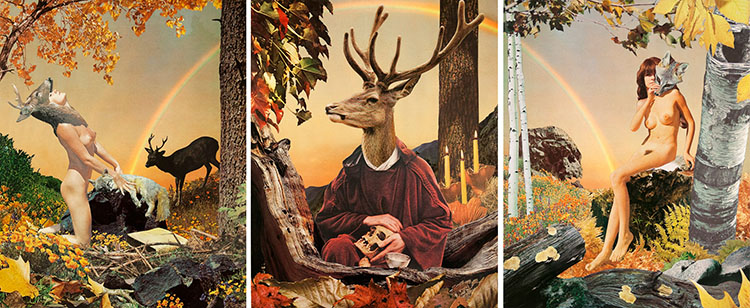

A Few More Wild Things. See more work by Jon Stommel.

A Few More Wild Things. See more work by Jon Stommel.

Fritz Ward. Dopplegänged. Lawrence, KS: Blue Hour Press, 2011. 44 pp. $10.00, paper.

Each poem in Fritz Ward’s debut chapbook, Dopplegänged, includes a reflection or refraction of the personal: a sometimes physical, sometimes metaphysical double. Andrew Webber, appropriately, finds a particularly German tradition for the literary apparitions of the dopplegänger, but does not end his categorization at simply the autoscopic action. The dopplegänger is typically male or masculine, usually nefarious, and absolutely “displacing”: there is no longer an original individual, no possibility to be unique. Ward’s idiosyncratic play with that malleable concept is a perfect choice for poetic investigations of language and identity.

Ward’s treatment of the dopplegänger is different than Søren Kierkegaard’s usage of the pseudonymic narrator. The dopplegänger trope allows Ward to live in double worlds, to offer the “multiple exposure” of the collection’s first poem. Ward shifts between prose poems and lineated pieces, and this first prose poem ends with a crisp sentence: “He stood there, shirtless—a camera at arm’s length, snapping himself at half.” The image is a nice introduction to the strangeness that follows. In “The Dopplegänger as Buddhist Trucker,” Ward creates a smooth, almost placid tone:

When the feathers separate

from the body, he remembers

how important his arm seemed

when he couldn’t move it,

and how, slowly, the trailer tipped

its glow of Florida oranges

onto the searing asphalt—

the interstate suddenly ripe

with bruised citrus, accidental

zest, pulp and shattered glass.

Even the delivery of these images feels extra-corporeal, as if the narrator is both absent and present in the moment, aware and detached. When we later hear the narrator say “Here’s the first person, no strings / attached,” we know he is lying, that duplicitous dopplegänger framing his moment in terms best suited toward his meaning.

That meaning, or focus, becomes clear a few poems into the collection: love. This is no ordinary romanticism. Ward extends his penchant for play to this emotion, and the choice is very successful. “Parenthetical Match” is clever, both in delivery and content. From the desire to “meet in secret,” to the anaphoric doubles in the center of the poem, to the concluding lines, Ward is most in his element when he lets his words spin:

It’s all thresh

and no hold. Come,

let’s bind ourselves

together—like a book

our parents dream

of burning.

The play continues in “The Dopplegänger’s Descant.” “Now teach me how to undress in a poem,” the narrator asks, before moving to the duality of the dopplegänger:

You should stare

and I should star. Yes, stare close

enough and I’m a lily that lends

to unending bending. I’ve never been won,

but one that is too.

Besides the love poems in the collection, Ward wanders into film, a medium absolutely suited to the dopplegänger. The action of viewing, the reversal of image from reel to mind, fits the title of the collection, the noun made verb: dopplegänged. Ward presents a drive-in, where “the screen is silver and immeasurable,” and “like us, the villains / are poorly lit. But we nibble, we gnaw, / we lick what we like.” In another poem, John Wayne’s “grit scours / the tongue in the sweat lodge of my mouth” and “One deep / breath from his solar plexus / is the nexus of excess.” The poem is titled “The Dopplegänger’s John Wayne,” and the next poem admits the dopplegänger might be “just his stand-in.”

Ward’s love poems and letters coalesce with his filmic approach, and for the result, think David Lynch’s Blue Velvet and Lost Highway. “Dear Cannibal Quivering with Lipstick and Moonlight” has a great title, but Ward still works for his images: “I stayed . . . to watch your soft hands flutter and flay / the green skin of the mango, its glistening flesh exposed, / alone on the white cutting board.” Ward’s wit is amply delivered in his ear for the texture of sound.

So what do dopplegängers and epistolary prose poems that conclude “love is merely a suggestion” have in common? That question needs further clarification. Ward’s dopplegänger opens so many poetic possibilities. Is this a double of the author, the narrator of the entire collection, or the narrator of individual poems? When the narrator states, in “The Dopplegänger at the Drive-In,” to “just up and fuck me, / I’ll mime the rest of my lines,” assumed gender becomes unclear. Such a move might be appropriate for a literature of the dopplegänger. Susan Yi Sencindiver’s contention feels appropriate here: “the dopplegänger decisively decenters the subject by subverting the logic of identity, [so] it cannot be presumed that gendered identity remains miraculously intact.” Words might connote masculine or feminine concepts, but letters are without sex. Ward’s collection decenters the reader, too, though his dynamic words make that displacement enjoyable.

Dana Levin. Sky Burial. Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon Press, 2011. 75 pp. $15.00, paper.

When the language of an exterior source usurps poetic meditation, the writing risks diffusion into ephemera. Some poets, however, assimilate into their verse this massa intermedia—an anatomical term for a functionless gray mass within the brain, used here to describe language dormant in its original context—so as to invigorate the writing, through adjacency, toward synaptic electricity. Dana Levin’s Sky Burial, with an aberrant prosody and form, uses transplant-language to create a pneumatic mutant of a voice, enrapturous as strange.

A “chorus comes roaring out of her / single mouth,” writes Levin in “Sibylline,” and although the allusion casts the poet as a kind of sibyl, perhaps she is less oracle than oracular medium and each poem, a quantum thereof. That’s not to say Levin meek or that she submits entirely to some external force, rather she asserts herself as the origin of the collection’s reckonings—most palpably with death which, stubborn and protean, invades the personal narratives of the poems, the consciousness, often leaving a speaker “Lost in the mind’s / imprisoned winds, its many-headed forms.”

Perhaps it is this multiplicity of the self that allows the myths of Xipe Totec, the Aztec god of Spring, and the Buddhist text, “Tsong Khapa’s Praise of the Inner Yama,” to speak for or with the speakers’ experiences, making the old relevant and the immediate entrenched in time and therefore, context. Consider the opening of “Refuge Field” in which the image making reflects the vicissitude captured between two voices:

You have installed a voice that can soothe you: agents

of the eaten flesh, every body

a cocoon of change—

Puparium. The garden

a birthing house, sarcophagidae—

Here again is death, but its origin is life. “O voice of a different timbre—,” one bows and ushers in another at the end of “Sibylline,” and though it might be said that the birth of one voice is the death of another, the Buddhist-influenced movements suggest rebirth of what’s lost—persons, civilizations, possessions—even if through poetry, the body in which all is re-manifest.

But the poems of Sky Burial are less elegies than tender autopsies in which Levin searches not for the cause of death but rather of life, the meaning of being the ritualizer instead of the ritualized. In this, the collection does not presume to reveal the ineffable but how to survive, transcend its silences.

“What is a body but a bag of alms,” asks the speaker in “Cathartes Aura,” and though what’s offered is sent, as the collection’s title suggests, in two metaphorical directions at once—skyward and into the earth—Levin offers all of it to the reader, in language that is succulent and invasive, following her own imperative: “Build it from rot.”

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nulla nec dui et nisi rhoncus tempor. Aenean lorem urna, posuere eu molestie tempus, dictum eget massa. Sed elementum gravida nibh, at dignissim sapien suscipit nec. Nullam rutrum nisl at velit adipiscing congue. Nam facilisis, dolor et ultricies laoreet, eros metus interdum mauris, eu placerat nibh libero egestas nisi. Donec venenatis lacus vel lectus porta pulvinar. In nec ultrices risus. Ut mollis, felis nec sodales fringilla, nunc libero ornare ipsum, a eleifend erat velit sit amet sapien. Fusce tincidunt placerat velit, id accumsan est molestie vitae. Cum sociis natoque penatibus et magnis dis parturient montes, nascetur ridiculus mus. Morbi scelerisque luctus purus. Aenean sed lorem odio.

“Cum sociis natoque penatibus et magnis dis parturient montes, nascetur ridiculus mus.”

Cras leo nisi, vulputate sed ultrices in, lacinia at dui. Nunc sit amet quam ligula, eu condimentum ante. Pellentesque varius, mauris tristique tempus rutrum, libero ligula mollis mauris, et porttitor metus velit at ligula. Cras at neque et arcu aliquet volutpat euismod non urna. Donec felis nulla, aliquet nec bibendum eu, porttitor laoreet quam. Suspendisse a libero tortor. Pellentesque lobortis ligula et odio sagittis at eleifend nulla euismod. Aliquam in lorem et velit fringilla tempus ac quis turpis. Suspendisse rhoncus sapien at neque ullamcorper eget dignissim nulla tempor. Mauris et aliquet arcu.

Donec tincidunt varius eros quis posuere. Suspendisse potenti. Integer elit ligula, scelerisque quis aliquam sit amet, accumsan in dolor. Nullam sapien risus, tristique sed aliquet quis, consectetur nec nunc. Mauris ac augue in ante laoreet dignissim. In iaculis, justo eget viverra scelerisque, nibh erat suscipit ligula, eu feugiat nunc neque non diam. Aliquam erat volutpat. Nunc imperdiet nisi et mauris posuere tempor et nec nunc. Curabitur diam urna, scelerisque id placerat et, posuere vitae mi. Quisque vel quam ut turpis tincidunt tempor. Mauris pharetra vehicula augue at eleifend. Aliquam enim nunc, molestie sit amet sagittis quis, faucibus sit amet nunc. Nullam in massa sit amet diam cursus semper id a leo. Vestibulum in elementum augue. Fusce malesuada venenatis mi, at laoreet turpis blandit nec. Aenean dignissim, dolor ut vestibulum accumsan, nulla risus eleifend ipsum, non sagittis justo lectus nec elit.